| Cover Story

From Bandarban

The Magic Lamp of Ongthui Khoy

Munira Morshed Munni  Walking through the hills of Bandarban, I had to stop to catch my breath. Chonumong, who was right behind me, also came to a halt. Because of the heat and humidity of monsoon, I was perspiring copiously. My two other companions, Ang Shing and Manowar Hossain Monu Bhai, were a bit far behind. I couldn't even see them through the dense forest. It's only possible to walk in single file in the hills since most of the pathways are very narrow and there are deep gullies on each side. As a result, there was a distance between my companions and me; and Monu Bhai and Ang Shing are always a bit slow. Walking through the hills of Bandarban, I had to stop to catch my breath. Chonumong, who was right behind me, also came to a halt. Because of the heat and humidity of monsoon, I was perspiring copiously. My two other companions, Ang Shing and Manowar Hossain Monu Bhai, were a bit far behind. I couldn't even see them through the dense forest. It's only possible to walk in single file in the hills since most of the pathways are very narrow and there are deep gullies on each side. As a result, there was a distance between my companions and me; and Monu Bhai and Ang Shing are always a bit slow.

As a professional photographer, I'd had many assignments in the past ten years but this one was still proving to be a challenge. Ali Zaker Bhai from Asiatic called me to take pictures of twelve personalities for the 2006 calendar of British American Tobacco. Zaker Bhai told me that the objective was to get pictures of twelve people who were unknown but extraordinary. They had devoted themselves to working for others without the need for fame or distinction. The vision of the calendar was to bring these remarkable people out of obscurity so that we may be inspired by them.

I had two of those twelve names in my notebook: Monjulika Chakma and Ongthui Khoy. Monjulika Chakma was a worker in Bein Textiles in Rangamati. Ongthui Khoy was a 48 year old who lived in Bandarban in the Maroma Palli Monjoypara village. Living eighteen kilometers above ground level, in the mountains, Ongthui Khoy made a breakthrough in the field of electrical energy. It was to get his picture that I was walking uphill to Monjoypara village.

The rain the night before had left the soil treacherously slippery. We had to walk barefoot, since sandals would easily get stuck in the mud. Our feet were completely covered in mud. I had already slipped twice. But fortunately Ang Shing and Chonumong had saved me from complete embarrassment. I had only met Manowar Hossain Monu Bhai, The Daily Star's local correspondent, the day before. An officer from British American Tobacco had introduced him to me in the bungalows of “The Guided Tour” in Milonchori. On my way to Monjoypara village in the morning at 8, I picked up Monu Bhai, Ang Shing and Chonumong up in my jeep from the Bandarban Press Club. Ang Shing is Ongthui Khoy's nephew. Chonumong's father is quite an influential man in these areas. Monu Bhai brought them along keeping in mind that we were about to travel to areas under the control of the Shanti Bahini.

Other than these three, I also had another male companion who I had brought from Dhaka. Usually, it is me who accompanies him during his tasks. This was the first time it was the other way around, and he was helping me out. After finding out that we would be climbing eighteen kilometers, he fell asleep in the jeep.

Chonumong and I had some water to prevent our throats from drying. If you try to climb the mountains too fast, your throat dries out and your heartbeat accelerates, so we were climbing slowly. Monu Bhai and Ang Shing finally caught up to us. We had stopped at a place that used to be inhabited by indigenous people, but now it was uninhabited. Sometimes the army raids their area in search of the Shanti Bahini, and as a result their neighborhood is scrambled. Monu Bhai exclaimed that there must be a fountain somewhere nearby. People always choose to set camps near water sources. Chonumong and I had some water to prevent our throats from drying. If you try to climb the mountains too fast, your throat dries out and your heartbeat accelerates, so we were climbing slowly. Monu Bhai and Ang Shing finally caught up to us. We had stopped at a place that used to be inhabited by indigenous people, but now it was uninhabited. Sometimes the army raids their area in search of the Shanti Bahini, and as a result their neighborhood is scrambled. Monu Bhai exclaimed that there must be a fountain somewhere nearby. People always choose to set camps near water sources.

We started walking again. Ang Shing pointed out a place and told us that he and his friends had once hunted deer there. Chonumong is, by nature, a quiet man; he doesn't say much. During the Liberation War of 1971, the freedom fighters used to hide in these mountains. Many indigenous people including Ang Shing's mother had given them food and shelter.

Monu Bhai and Ang Shing had fallen back again. Monu Bhai was calling out to Chonumong as he was lagging behind. Chonumong placed his finger on his lips as a sign to tell me to stay silent. It was amusing, and I smiled. Our silence would lead Monu Bhai to think that we are quite far ahead, and thus make him walk faster. We had climbed quite high by now. We were close to Ongthui Khoy's house. The natural beauty of the hilly region was magnificent. There were hills of different sizes that were different shades of green. Above that were white clouds, and below, the topographical composition was amazing. From time to time, I could spot a hut in the lap of the mountains; as if stolen from a dream. These huts were usually used for storing food grains or for security purposes of agricultural plantations nearby. Inside there would be benches made out of bamboo. Ali Zaker Bhai had told me that I could take pictures of the other chosen personalities if this particular job seemed too dangerous for me. In the last six years, I had to travel to many remote parts of Bangladesh to take pictures for UNICEF. I had to live completely by myself. To witness the shooting of my friend Morshed's film, I had to travel through mountains, oceans, and rivers and and through many other equally perilous landscapes, but this journey was still special. It was unlike any other. Even though it was a lot of hard work, I kept telling myself that I had to go through with it. This man had transformed water flow energy in the lake next to his house to electrical energy completely through his personal efforts! I simply had to take his picture.

Ang Shing was in front of us, leading the way forward as we followed. Going up a steep staircase, we entered Ongthui Khoy's house. A man of lean build in his middle ages, Ongthui Khoy, came out smiling. He does not understand Bangla and so Ang Shing had to play the role of the interpreter. Ang Shing had notified Ongthui Khoy regarding our visit a day in advance but because of the rain, he had presumed that I might not show up. He did not imagine that a Bengali girl would dare to travel the slippery path full of obstacles that leads to his house. Ang Shing was in front of us, leading the way forward as we followed. Going up a steep staircase, we entered Ongthui Khoy's house. A man of lean build in his middle ages, Ongthui Khoy, came out smiling. He does not understand Bangla and so Ang Shing had to play the role of the interpreter. Ang Shing had notified Ongthui Khoy regarding our visit a day in advance but because of the rain, he had presumed that I might not show up. He did not imagine that a Bengali girl would dare to travel the slippery path full of obstacles that leads to his house.

The house had been constructed on a raised platform made of bamboo so that wild animals could not come in. As I climbed the wooden stairs, I noticed farm animals, namely cows and goats beneath the bamboo platform. Ongthui Khoy's wife brought water so that the four of us could wash the mud off our feet. Through the bamboo porch, we walked into a cool wooden chamber; its walls and floor were all constructed with wooden planks. We were all exhausted, and let our tired bodies loose on the floor. Ongthui Khoy's wife started cooking as cold water brought us back to life; the smell of food seemed to churn our stomach, making us even hungrier.

I started to throw questions at Ongthui Khoy, “Why did you want to create electricity?”

He replied, “Because it is the source of light. As a child I couldn't go to school because there are none in the area. The indigenous villages are all mostly dark; they are disconnected from modern amenities. The people here not only suffer from the lack of lighting but the light brought about by education and knowledge is also absent here. My efforts were to eradicate that darkness in these villages.”

“How were you motivated?”

“Whenever pumps, generators and other machinery went out of order in the village, I used to take a personal interest in fixing them. I love tinkering with mechanical parts. Once when I was fixing a broken generator, the idea of a wooden turbine struck me. I earned eighty thousand taka by selling trees and used that money to arrange and collect the things I would need. I did not have enough money to revolve the turbine using kerosene as fuel, so I planted the turbine in the lake beside my house. I used the power of the water flow as the fuel that would constantly keep the turbine in revolution, and inevitably I realized that all I need to do now is convert that energy to electricity.”

|

Ongthui Khoy's wife in the kitchen |

Ongthui Khoy used to travel eighteen kilometers by foot to buy required machinery and tools from Bandarban town. He used get a lot of help from his nephew Ang Shing, since Ang Shing had a diploma in electrical engineering. He started his project in the year 2000, and achieved success in a matter of only one year. It was like magic! He managed to supply electricity to a hundred households! Monjoypara village had been illuminated by the radiance of his brilliance. His eyes sparkled at the lights that glow using the energy he supplied. The indigenous children who are not lucky enough to go to school yet could at least read books in the electrical lighting. The whole village seemed to gleam.

But all good things must meet their ends. The mighty forces of the monsoon river destroyed the wooden turbine. To restart his project he was about to sell trees and borrow money again. But through Ang Shing, journalist Manowar Hossain Monu Bhai learned about what happened and came as fast as he could to report the news. Ongthui Khoy's story was published in the Daily Star. The UNDP showed and interest in making it a permanent project.

Ongthui Khoy started to receive invitations from many important events and programs. His work was being applauded by many. Print and electronic media started to cover him. Ongthui Khoy just kept on smiling in his shy modest manner, but now he has started dreaming big. To make his project legal and to restart on a much larger scale, he submitted his Project File for approval in the Department of Environment of Bangladesh. Till now, so many people from the media have come and gone, Ongthui Khoy wonders why a letter from the Department of Environment has not yet arrived.

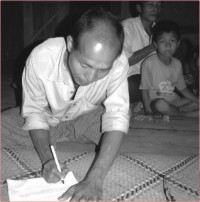

The project wasn't there for our eyes or my lens to see, so I simply framed my shot of Ongthui Khoy with the Hanra Lake in the background. I wanted a cheerful picture, but before I could press the shutter, his face became gloomy. To quickly make the situation better, I placed my fingers on the shutter and my eyes on the viewfinder, and asked Ang Shing to translate my question, “There are so many people coming from Dhaka and Bandarban town; your wife is having a hard time playing host to so many people. Do you want to marry another one?”

The father of two children leaked out a smile, and that's exactly what I was waiting for. I pressed the shutter, and he then moved his head sideways saying a firm “No.” His children are still deprived of basic rights. They do not have access to schooling from here; neither did he when he was a child. So, he keeps his children at relatives' houses in Bandarban town, from where his 10 and 14 year old children can go to school. The father of two children leaked out a smile, and that's exactly what I was waiting for. I pressed the shutter, and he then moved his head sideways saying a firm “No.” His children are still deprived of basic rights. They do not have access to schooling from here; neither did he when he was a child. So, he keeps his children at relatives' houses in Bandarban town, from where his 10 and 14 year old children can go to school.

After the photo session, we had a filling lunch with rice, potato cooked in dried fish and chicken cooked in a lot of green chili. After the meal, Ang Shing and Chonumong hurried us to get out as soon as possible. After all, we had eighteen kilometers of backtracking to do, down the hill before darkness fell.

On our return, Ongthui Khoy showed us an alternate route which was a bit more favorable. He started walking with us as well. We made our way back through the ankle-high waterway of the clear Hanra Lake. About half a mile down the way, Ongthui Khoy shook our hands and bid us farewell.

So many corrupt businessmen are still opening up factories and mills that keep degrading and polluting our environment. But people like Ongthui Khoy remain in the darkness with unfulfilled noble dreams. Simple and modest, he is now keeping his neighborhood's lights on by using kerosene generators, and he is dreaming of someday establishing the alternate means of generating electricity. He is dreaming of making his project permanent. He is dreaming of illuminating his entire village in the fight against darkness and the struggle against illiteracy.

Translated by Zahidul Naim Zakaria

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |