|

Eid Special

Colorful Memories of a Colorless Eid

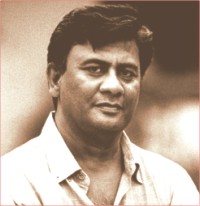

Prominent film director and film activist Tareque Masud studied in madrassahs in his youth and later in life took a turn into filmmaking. Here he reflects Upon his varied childhood.

When I think about my childhood memories, Eid Day comes to mind. Eid used to be in winter when I was little. Maybe for this reason, winter is strongly associated with my childhood memories. All the boys used to gather at the pond to bathe on winter morning of Eid Day. What fun it was! Our bones were already shaking from the chill winter air. How could it be fun to submerge ourselves in the freezing water? It's amazing to think of it now. Then we'd go for Eid prayer, dressed in our new starchy white clothes. At such a young age, children generally like to wear colorful clothes, particularly on festival days. I remember once having received an Eid present from one of my uncles: a bright red shirt! While wearing the usual white pajama-panjabi combination, I could hardly wait to put on my colorful new shirt. But I needed some excuse. So during lunch I deliberately spilled yellow curry on my white panjabi. As expected I got a scolding from my mother. "Go and change your clothes!" my mother yelled. When I asked whether I could wear the shirt given by my uncle, my mother immediately understood the whole ruse. She consented with a knowing

This stain episode made such a strong mark on my memory that I later made a sequence out of it in my film Matir Moina. Like me, Anu also deliberately stains his white panjabi so he can wear the colorful shirt given by his Uncle Milon. Later, Anu and Asma go for a stroll with Uncle Milon in the village. As they walk along, Anu asks Milon "Tell me Uncle, Eid is a fun day, so why do people wear white?" Finding no explanation at this unexpected remark, Milon replies, "That's a good question!" This stain episode made such a strong mark on my memory that I later made a sequence out of it in my film Matir Moina. Like me, Anu also deliberately stains his white panjabi so he can wear the colorful shirt given by his Uncle Milon. Later, Anu and Asma go for a stroll with Uncle Milon in the village. As they walk along, Anu asks Milon "Tell me Uncle, Eid is a fun day, so why do people wear white?" Finding no explanation at this unexpected remark, Milon replies, "That's a good question!"

I grew up in the village surrounded by pagan pujas and parbans, fairs and festivities. I saw how not only clothes, but everything festive was an explosion of colors. Naturally, I used to wonder why our own festivals were so pale and drab by comparison. Now I'm older, but like Uncle Milon, I still have no answer. However, this is perhaps a problem likely to happen when you try to unquestioningly adopt the culture of a religion's origin place along with the creed. In Saudi Arabia, when thousands come together for Eid prayers under the harsh desert sun, white clothes are essential for deflecting the heat and harmful rays. In Christian culture, white is the symbol of light and life, which is why the bride's dress is white, not red like ours. Likewise, in Christian culture anything negative is associated with 'blackness': black money, black market, black laws, black day, and of course, death itself. On the other hand, in our Eastern culture, the color of mourning and death is white, not black. That's why I always wondered, why don't we use a white badge as a symbol of mourning on Ekushey February instead of black? Perhaps this is again example where we have unquestionably adopted a culture of color from another place, one that is rooted, in this case, in the West.

We children used to have fun with the ritual of 'kolakuli' (embracing). Often our Eid day kolakulis would melt a long-standing silence between friends prompted by an earlier 'jhogra' (petty dispute). Irrespective of young and old, rich and poor, kolakuli represents the egalitarian spirit of Islam and the strong sense of fraternity it preaches. On the other hand, the ritual of touching the feet of our elders represented an acknowledgment of seniority and hierarchy. We didn't mind, because for us it was a chance to collect some pocket money to spend on sweets and toys. But it never occurred to us when we were little that kolakuli and wearing white clothes was confined to the male domain. The sense of fraternity reflected in the homogenous sea of white clothes worn by men standing shoulder to shoulder during Eid prayer has no parallel amongst women. Women don't have to wear white, nor perform kolakuli, nor go for the Eid prayer. It didn't occur to me then that if women participated in all these rituals, who would do the cooking for so many guests? After all food is the center of our Muslim festivities.

I want to conclude with a small childhood memory that also became part of Matir Moina. Recalling the colors of my childhood associations reminds me of the loss of my sister when I was very young. Like other children, my older sister was also drawn to bright colored things. I tried to bring this out in Matir Moina, but in a slightly different way. When Asma takes a walk with Anu bhai and Milon kaka on Eid Day, they pass a cluster of wild flowers. Asma asks Milon to bring her a flower, and he naturally moves towards a red flower. But Asma's voice is heard, telling him, "Bring me that white flower over there!" Milon picks the white flower and gives it to the delighted Asma. The audience may notice that the place where the white flower grew is the same place where Asma will later be buried. Did Asma, who loved colorful things, have a premonition of her own death? Or is white not only a representation of death, but also of childhood innocence? Maybe both--white as a color of sacred innocence.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2007 |