| Cover Story

From Insight Desk

Romesh Shil:

The Tale of the Kobiyal

Saba El Kabir

In the world of Kabigaan, Romesh Shil is a legendary figure. In his time, he was the undisputed master of the art. He would take on three kabiyals at a time, on the same stage, and would inevitably prevail. From the backwaters of Chittagong to center-stage of Calcutta's famed Mohammad Ali Park, all has experienced his poetic feats. In this issue's cover story, we look at Romesh Shil the man, the kabiyal, and the icon. In the world of Kabigaan, Romesh Shil is a legendary figure. In his time, he was the undisputed master of the art. He would take on three kabiyals at a time, on the same stage, and would inevitably prevail. From the backwaters of Chittagong to center-stage of Calcutta's famed Mohammad Ali Park, all has experienced his poetic feats. In this issue's cover story, we look at Romesh Shil the man, the kabiyal, and the icon.

Of Beginnings

His name was Romesh Shil. Had been addicted to music since his childhood, constantly lost in his own world of rhymes and melodies. When his father - on whom the family was completely dependent for its upkeep - died, the 11-year-old Romesh was thrust into the role of the provider. At 12, he set off for Akiyeb, Myanmar, and worked at a barbershop for seven long years. At 19, the music drew him back to Bangladesh. He would take off on a moment's notice to the jolshas of the neighboring villages, an unfettered youth, the man of the house.

At the time, the the Sadarghat area of the city would host the annual “Jagadattri Puja” with much fanfare. The central attraction of the event was Kabigaan. It would draw a big crowd, a crowd that would inevitably include the young Romesh Shil. Around the year1898, two heavyweight kabiyals, Chittaharan and Mohon Bashi, have taken the stage, ready to start the battle of the verses. But before things could get started, the venerable Chittaharan lost his voice. The crowd was not happy, and they began to show it. The announcement was made - if there is there is another kabiyal in the crowd, please get on the stage. Romesh was still more a kid than a kobiyal, but his friends force him forward, and a scared and shaking Romesh Shil found himself on the stage. And the rest, as they like to say, is history.

The topic of debate for the day was Shurponokha versus Modhu Doitta, two characters from the Ramayana. Before the debate would start in earnest, the opponents would take turns introducing each other. Here the veteran kobiyal took some well-aimed shots at the young pretender, branding him “the little brat”, barber, among other things. In response, this was Romesh Shil's first verse :

Uttshaha ar bhoy (Enthusiasm and fear)

Lojjao kom noy (And a bit bashful)

Keba thamaybe kare (But who can stop whom?)

Puchke chora shotti mani (I may be a little brat)

Shishu Dhrubo chilo gaani (But the child Dhrubo was ever wise)

Chena jana hokna a ashore (Let us get to know each other on this stage)

|

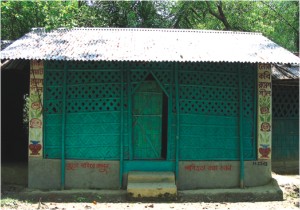

Kabiyal Romesh Shil's burial chamber |

The power of young Romesh's logic and presentation grew in precision and strength from one verse to the next. The night came to an end, as did the following morning, and the afternoon, and then the evening. But there was no end in sight. The organizers were forced to arrange a truce between the two, and Romesh Shil was given a prize of cash money. Word of the “new kabiyal” spread hard and fast. From then on, Romesh Shil became a regular fixture at any gathering of note in the region.

Slowly but surely, his fame began spread out across the entire nation. Beyond Chittagong, he first performed at the 8th conference of provincial farmer's union North Bengal's Hatgabindapur. This was the first time he revealed himself in front of all the leftist elements of Bengal. That same year, he found an even bigger leftist stage for himself, when he performed at the 3rd annual conference of “Anti-fascist Writers and Artistes Union”, in Calcutta. In 1948, he performed at the “All India Farmers Conference”. Kobiyal Romesh Shil sung his songs for over six decades, and ushered in a new era for his much-loved art.

Kabigaan and Romesh Shil

The last half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century is generally regarded as the golden age of Kabigaan. In an age without the mass media, the kabiyals were the trusted information-merchants of society. Kabigaan traditionally got its subjects from the Hindu classics and other folk myths. Popular topics included: Ram - Rabon, Radha - Krishna, Shurponokha - Modhu Doitta, Naradh - Mohadeb, and Hanifa - Shonabanu. What set Romesh Shil apart was that he broke out of this mould and chose his own subjects: Man- Women, Truth - Lies, Sadhu - Grehasta, Master -Disciple, Gold - Iron, Rich - Poor, Wealth - Knowledge.

|

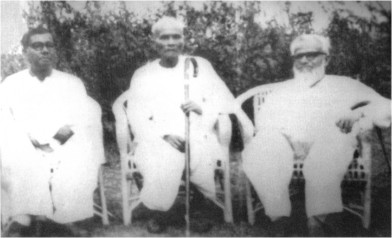

| Koabiyal Romesh Shil (centre), with Polli Kabi Jasimuddin (left) and poet Abul Fazal |

As time went by, his songs became even more socially-aware. When he came in contact with the Indian Communist Party, the songs took on an entirely new dimension. He started to address more complex ideas: Wealth - Science, War - Peace, Farmer - Labourers, Farmers - Landlords, Autocracy - Democracy, Capitalism - Socialism. The changes he introduced to kabigaan were nothing short of revolutionary. By making kabgaan socially-aware, he made it more relevant to society than it had been ever before. In the 200 year old history of kabigaan, this was a fundamental change.

Another of his major contributions was the refinement of the kabigaan language. In the eighteenth century, the use of expletives in kabigaan was standard practice. Spiced-up descriptions were the main attraction of most of the songs. By choosing to abandon this trend, Romesh Shil made kabigaan much more intimate to the lives of its audience. Instead of juicy songs about mythic subjects, his songs dealt with the vicissitudes of life, and there was simply no place left for the spice. In place of racy songs, sung in the haze of late-nights, accompanied by the din of drums, Romesh Shil would sing:

Ak jagate darai jodi chasi mojurgon (If we farmers and laborers stand together)

Akasher chan matite ante lage kotokkhon (How long can it take to bring down the moon from the sky)

Na karile dukha born shukher asha dekhi na (If we do not accept the pain, we cannot hope for happiness)

His third significant contribution to kabigaan was the innovations he introduced to its structure and formats. In the 18th century, the formats and constituent parts of kabigaan generally included the following;

* Bhabani Bishoi: Hymns honouring goddesses or gurus

* Shokhi Shongbad: Songs about Radha-Kirshna

* Biraha: Songs about the estrangement of Radha-Krishne

* Kheyur: Hindu classics and myth based interplay

* Lohor: Personal attacks and counter-attacks of the opposing kabiyals

* Jotok: Songs sung in closure, in case the kabigaan session yields no victor

Romesh Shil replaced Bhabani Bishoi with hymns for the motherland. Instead of Shokhi Shongbad, his songs would greet the audience, or describe various passages from history. In the Biraha segment, he would sing folk songs, spiritual songs, and rhymes. More often than not, he would choose the role that is apparently more difficult; the goal being not victory, but the refinement of his art.

The refinements Romesh Shil introduced to kabigaan was not confined to just himself and his disciples. His unique blend of creative prowess and organizational zeal spread across the expanses on the undivided Bengal. We would not be too far away from the truth in claiming that kabigaan, as we know it today, is in fact mostly Romesh Shil's kabigaan.

The kobiyal and his time

Romesh Shil spent over six decades traversing from one end of Bengal to the other with his musical troupe. Both physically and ideologically, his music never found itself in the same place for too long: sometimes extremely nationalistic, sometimes deeply communist, while at other times intimate to the spiritual philosophy of Sufi Maijbhandari. When Khudiram was hung at the gallows, he sang:

Dhonno chele mayer kole

Aka geli chole.

Thakte tetrish koti bhatra, shongi fele

Aka holo Khudiramer fashi.

In his later years, involved with the Six Point movement of Bangladesh, he would sing:

Sharbajonin bhot bhai, protokho nirbachan chai,

Aro chai ancholic shaitto shashan.

The body of work he has left behind talks of all major socio-political events over the six decades of his kabiyal career. He was always a keen observer of humanity, and from the vantage point of demonstrations, political gatherings and prisons, he would observe the ebb and flow of society, and record them through his songs and poems. He had lived through the First World War, the Non-Cooperation Movement, Chittagong's Youth Revolution, the Second World War, the subcontinent's Race Riots, Bangladesh's Language Movement, election of the United Front, Ayub Khan's military rule and the Six Point movement. Little wonder than, with the weight of all these intense experiences behind him, that without any form of formal training or education, the kobiyal was able to construct his masterpieces, such as his epic poem “Jatiya Andalan”.

In the 1940's, he joined the Indian Communist Party. The communist party mouthpiece the “Janajuddha” periodical had a influential part to play in his induction. On this, he said:

“Suddenly I ran into a boy I had known for a while. He was carrying a publication. It had 'Janajuddha' written on top of it. The boy said, take it, have a read. Took it home, read it front to back. I never had the chance to get to know my country like this. Really felt encouraged to start writing again. I had the urge for a while, I finally found the means.”

The following decades saw the influence of the communist ideals and agenda increase steadily on his work. He would sing to the workers:

Amar khune motor gari, tetala choutala bari

Tomar khune radio ar bijli bati jole

The kabiyal life was never easy. Scarcity and suffering was chronic throughout. But he never deviated from his ideals. In 1958, he was arrested for his opposition of military rule, putting to an end the “literary stipend” he used to receive from the government. Even then he refused to give up. Sitting in his prison cell, at the age of 77, he wrote

Banglar jonno jibon gele hobo shorgobashi

Amar thik thakibe Banglar dabi jodio hoy jel fashi

Each year, on the last week of the Bengali month of Chaitra, the kobiyal's old home takes on a new guise. A decorated stage is constructed for the groups of harmonium and dhol wielding poets. They battle it out with each other, just like they used to in the old times. But they don't do it for the thrill of victory, nor the ideals of refining their art, but to honour the memories of the master kabiyal, Romesh Shil, on his death anniversary. In the spirit of these battles, the spirit of Romesh Shil lives on, and it continues to sing the jotok:

Ak jagate dara-e jodi chasi mojurgon,

Akasher chan matite ante lage kotokkhon.

Romesh Shil through the years

* Kabiyal Romesh Shil in 1877, in the village of Gomdondi, under Boyalkhali thana of Chittagong district.

* Realizing his passion for music, his father buys him a book called “Brihat Tarjar Lorai”. This was a book on improvised verses, in a competitive context. This was perhaps the moment that sealed the kabiyal's fate for life.

* In 1887, his father dies, leaving a 11 year old Romesh Shil to fend for his family.

* In the face of extreme poverty, he leaves for Akiyab, Myenmar, and works at a barbershop for seven years.

* Romesh Shil returns to Bangladesh in 1895.

* In 1898, performs kabigaan for the first time on a stage in Chittagong's Sadarghat Jelepara, and achieves widespread fame overnight.

* In 1923, arrives at the famous “Maijbhandar Urash” in Najihat. There he meets the Maijbhandar Peer Golam Rahman, and writes the song “Iskool khuilase re moula, iskool khuilase”, a song that is popular to this day.

* In the 1940's, he comes in contact with the Communist Party of India, and becomes a member in 1944.

* In 1952, he writes songs for the Language Movement, and actively participates in it.

* In 1954, actively participates in the election, on the side of the United Front.

* In 1958, he is incarcerated for opposing the military rule of Ayub Khan, and “Bhot Rahassha” (The Vote Mystery), a pamphlet he wrote, is banned.

* In 1969, Romesh Shil passes away.

* In 1993, Bangla Publishes a collection of his entire body of work, “Romesh Shil Rachanaboli”.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009

|

|

In the world of Kabigaan, Romesh Shil is a legendary figure. In his time, he was the undisputed master of the art. He would take on three kabiyals at a time, on the same stage, and would inevitably prevail. From the backwaters of Chittagong to center-stage of Calcutta's famed Mohammad Ali Park, all has experienced his poetic feats. In this issue's cover story, we look at Romesh Shil the man, the kabiyal, and the icon.

In the world of Kabigaan, Romesh Shil is a legendary figure. In his time, he was the undisputed master of the art. He would take on three kabiyals at a time, on the same stage, and would inevitably prevail. From the backwaters of Chittagong to center-stage of Calcutta's famed Mohammad Ali Park, all has experienced his poetic feats. In this issue's cover story, we look at Romesh Shil the man, the kabiyal, and the icon.