|  Cover Story Cover Story

From Insight Desk

Master Da's Revolution

Saba El Kabir

According to British records, one of the "most spectacular and successful" revolutionary actions in colonial India took place right here in Bangladesh, in the somewhat unlikely political backwaters of Chittagong. The Chittagong Jubo Bidraha (Youth Revolution) of 1930 was a dramatic chain of events that started off in April 18, and saw its protagonist, Master Da Surjya Sen, and his band of revolutionaries raid British armouries, hoist the flag of an independent India, and declare the liberation of Chittagong under a Provisional Revolutionary Government, under the mandate of the Indian Republican Army.

Much has been written about India's independence movement, but as always, an objective view of history tends to be elusive. Popular history puts the luminous figures of Gandhi, Nehru and Jhinna, deservedly, in the center-stage of the movement, but somewhat unfairly relegates the likes of Master Da Surja Sen to bit-part roles. Yet, arguably, the daring raids of the Chittagong armouries, and the open defiance of the military might of the Queen's army by a group of idealistic teenagers and men and women of thought, did as much to weaken the Union Jack in the sub-continent as the “Salt March” or “Non-Cooperation Movement”.

The revolutionary elements of the nation were themselves as surprised as the British administration at the success of April 18. Of course, if one was to look at the Jubo Bidraha in isolation, between the ceremonies of the flag, the glories of the battlefield and the death of martyrs, one might find it hard to understand what exactly was achieved. But putting it in the context of Indian independence, the picture becomes clearer.

What Surjya Sen and his revolutionaries achieved was not 15 minutes of fame, neither was it a petulant act of anarchy. The group was fully aware that whatever was achieved on the day, it would be temporary, and would most likely cost them their lives. But whatever was achieved on the day would be nothing compared to what would be achieved on the day after. The reverberations of their actions and sacrifices swept across all of India, and the aftershocks were quite acutely felt across the oceans, at the seats of power in Whitehall and Westminster.

|

| The gallow where Surjya Sen was executed |

There are definite parallels to be drawn between Chittagong's Juba Bidraha of 1930 and the Dublin Easter Revolution of 1916 (in fact, in his last note before he was executed, Surjya Sen refers to 18 April, 1930 as “the day of Easter Rebellion in Chittagong”). On the eve of Easter, 24 April 1916, the Irish Brotherhood, under the leadership of a school teacher took over military and civil installations, and declared the independence of Ireland. The uprising was violently suppressed after seven days of fighting, its leaders court-martialed and executed, but it forced a definite shift in the political landscape of the United Kingdom. In the 1918 General Election to the British Parliament, the republicans won a clear majority on a platform of abstentionism and Irish independence. Similarly, the 1930 Juba Bidraha set off a wave of violent patriotic fervor - assassination attempts, mutinies, bombings - forcing the British hand in enacting the Government of India Act 1935, the last pre-independence constitution of India, which granted a large measure of autonomy to the provinces of British India. It is perhaps worth mentioning that through their armed action in 1930, the leftist and underground elements in the independence movement made a place for themselves in mainstream politics, when the senior Congress leaders suavely used the threat posed by “terrorism” as a bargaining chip in negotiations with the British Government.

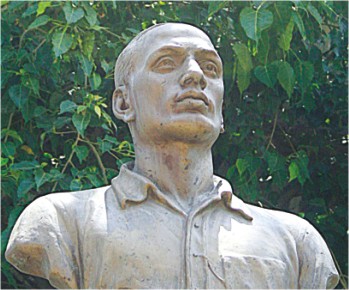

Who was Surja Sen

Master Da Surja Sen was not one of those charismatic revolutionary figures, able to inspire thousands by their sheer presence. Nonetheless, inspire he did. His appeal was of the simpler, more down to earth kind. His fierce inner strength, and dedication to his dream of independence, would compel those around him to instinctively believe in something that, at that time, would have seemed like distant pipe dreams to most. His ability to rally and organize the youth around his visions and then pursue them, unflinchingly, to the very end, has earned him a box-seat in the revolutionary lore on Bangladesh and sub-continental India.

His father's name was Ramaniranjan, a resident of Noapara in Chittagong. Sen was initiated into revolutionary ideas in 1916 by one of his teachers while he was a student of Intermediate Class in the Chittagong College and he joined Anushilan, an underground political organization. When he went to Behrampur College for BA course, he came in contact with Jugantar, and found that their ideas were more compatible with his own. On his return to Chittagong in 1918, he took up the organizational responsibilities of Jugantar there. In 1929, Surjya Sen became the secretary of the Chittagong district committee of the Indian National Congress, and used it as an umbrella for his work with Jugantar.

He became a teacher of the National school in Nandankanan and then joined the Umatara school at Chandanpura, earning him his moniker of Master Da.

Prelude to the Juba Bidraha

In the late 1920's, the political barometer of India was not quite hitting battle-pitch, but it was approaching it. Gandhi has embarked on his “Salt March”, and Nehru and other senior leaders of Congress are organizing political demonstrations and gatherings in open defiance of the law. Hundreds of party activists are being arrested every day. Subhash Bashu, another high profile leader, has already been incarcerated. The seeds of rebellion have been sowed in all corners of society.

A few days before 18 April, Mahim Das led the Salt March from the Kumira beach of Chittagong. Master Da Surja Sen, as the General Secretary of Congress in Chittagong, was encouraging the population to participate in the “Salt March” and “Non-cooperation movement”, and while secretly perfecting his master plan for Juba Bidraha. It is safe to say that Gandhi's principle of non-violence was not foremost in his mind.

The preparations for Juba Budraha, or at least some form of armed uprising, had started years in advance. Jugantor, a political organization under the leadership of Surjya Sen, had been steadily building a number of fitness clubs in and around Chittagong, namely Sadarghat Club, Brindaband Akhra Club, Chandanpura Club and Dewen Bazaar Club. Anushilon, another political organization with similar ambitions to Jugantor, also built a couple clubs of their own Nandankanan Club, Dewan Bazaar Club. These clubs were the means for these organizations to recruit young revolutionaries in their ranks, and train them up so that their bodies are able to keep up with the revolutionary zeal of their spirits.

|

|

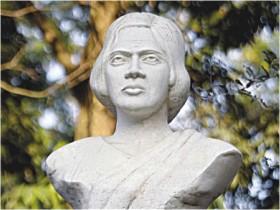

| Pritilata Waddedar, a key figure of the Juba Bidraha |

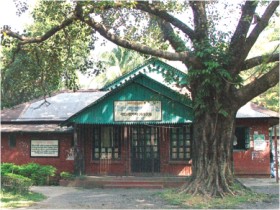

Chittagong's European Club, many patrons of which

were targetted by the revolutionaries |

If we are allowed to put forward a conjecture, specific planning began perhaps as far back as 1928, when Master Da started visiting the Dastidaars, a politically influential family of Chittagong on a regular basis. Kalpana Datta and Pritilata Waddedar, two very significant characters in the Jubo Bidraha episode, would also regularly visit during the Dastidaars during this time. In the small world of Chittagonian politics, this was perhaps too much of a coincidence to be just a coincidence.

The Jubo Bidraha

Master Da Surjya Sen, who along with five others Nirmal Chandra Sen, Lokenath Bal, Ambika Chakravarty, Anant Singh and Ganesh Ghosh led a young band of revolutionaries in open revolt against the Imperial British administration in Chittagong. The plan was to take control of the two armouries, destroy the central telephone exchange, cut all external telegraphic lines, remove railway lines and cutoff train communications, isolate Chittagong, and establish a “Provisional Revolutionary Government”.

However, despite years of meticulous planning and careful coordination on the night of April 18, 1930, things did not go as planned. Once they took control of the armouries, they discovered, to their horror, that the armouries did not have a supply of ammunitions. Circumstances on the night also led to the revolutionaries being separated into a bigger and a smaller group.

The bigger group, largely comprising tired but adrenaline driven teenagers who did not yet realize the extent of their setback, gathered outside the police armoury where Surya Sen took a military salute, hoisted the National Flag and proclaimed a Provisional Revolutionary Government. Having made the proclamation, the group retreated. The revolutionaries left Chittagong town before dawn and marched towards the Chittagong hill ranges at Jalalabad, looking for a safe haven.

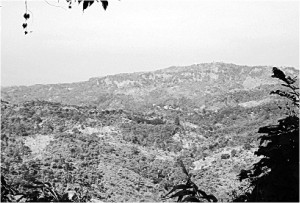

|

| The Jalalabad Hills, the site where Surjya Sen's Indian Republic Army made its last stand |

Meanwhile, the British administration, unaware of the setbacks faced by the revolutionaries, panicked, boarded a foreign ship and sailed out into the sea. From there, they were able to send a wireless message to Calcutta fort to send immediate help to Chittagong. Four days later, 22 April, an Imperial army containing a few thousand Gurkhas, Marhattees and Dogras, surrounded the rebel position in Jalalabad Hill, and in the small hours of the morning, began their assault. What followed was nothing short of heroic.

This rag-tail group of 55 adolescents and intellectuals, calling themselves the Indian Republican Army, poorly armed and desperately short of supplies, took on a fully armed battalion of British troops, and repelled wave after wave of Imperialist assaults. At one point, they mounted a counter-attack of their own and forced their way out of the siege. 12 of the revolutionaries lost their lives on that day. Multiple sources have claimed that around 80 of the British troops were killed, but history has the tendency of distorting the numbers in favour of the eventual victors.

Over the following years, although Surjya Sen went into hiding, his actions incited a spate of revolutionary action throughout the sub-continent, although none would even attempt to match the sheer audacity of Surjya Sen's Jubo Bidraha. He was eventually caught, and sentenced to the gallows. The British, anxious about not creating martyr for the population to rally around, dumped his body in the waters of the Bay of Bengal. But what the British overlooked was what Surjya Sen so eloquently put in his last note:

At such a pleasant, at such a grave, at such a solemn moment, what shall I leave behind for you? Only one thing, that is my dream, a golden dream - a dream of freedom.

Photos by Anurup Titu

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009

|

|