| Cover Story

From Insight Desk

Bishadh-Shindhu

In the ever-changing world of music, changes are

sometimes welcome, sometimes controversial and

Sometimes downright loathed.

The inclusion of Mir Mosharraf Hossain's 'Bishadh-Shindhu

in the repertoire of the jari troupes of Netrokona is an example of the former. The masters of the genre explain how this text is

converted to songs using locally composed music.

Saymon Zakari

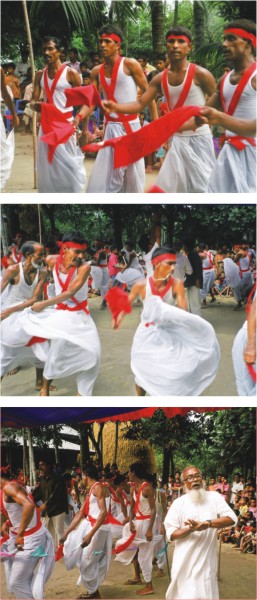

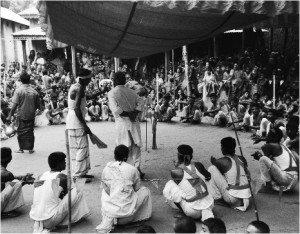

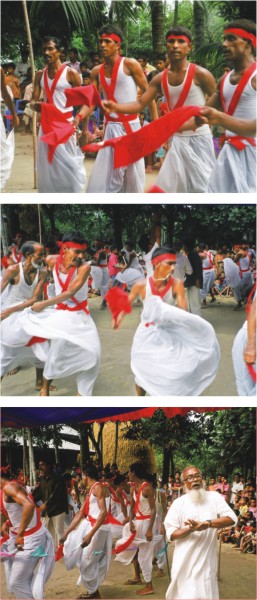

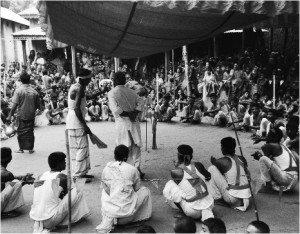

JARI songs are one of the popular branches of traditional performing arts of Bangladesh, which are the backbone of the country's folk arts. On the 10th of Muharram, in the 61st year of the Islamic calendar, Imam Hossain, the grandson of Islam's last Prophet Muhammad (SAW), was martyred brutally alongside his family at Karbala, Iraq. Bengali Muslims, who based them on the martyrdom of Imam Hossain, composed jari songs. Although the songs were initially only based on these events, their popularity caused the inclusion of other stories into the genre. The poet Jasim Uddin did extensive research on the subject and included in his repertoire not only the usual jaris about the events in Karbala, but also about the baptism of Mecca, the exile of Hajera, Kurbani, Yousuf, Kulsum's Mezbani, Anaal Haque etc. However, on the 25th of May 2009, we learned something new while we were on a research trip for jari songs in the village of Pachhaar located in Kendua Thana in the district of Netrokona - that Mir Mosharrof Hossain's famous novel 'Bishadh-Shindhu' has been performed by jari musicians in and around the area for the last 50 years. JARI songs are one of the popular branches of traditional performing arts of Bangladesh, which are the backbone of the country's folk arts. On the 10th of Muharram, in the 61st year of the Islamic calendar, Imam Hossain, the grandson of Islam's last Prophet Muhammad (SAW), was martyred brutally alongside his family at Karbala, Iraq. Bengali Muslims, who based them on the martyrdom of Imam Hossain, composed jari songs. Although the songs were initially only based on these events, their popularity caused the inclusion of other stories into the genre. The poet Jasim Uddin did extensive research on the subject and included in his repertoire not only the usual jaris about the events in Karbala, but also about the baptism of Mecca, the exile of Hajera, Kurbani, Yousuf, Kulsum's Mezbani, Anaal Haque etc. However, on the 25th of May 2009, we learned something new while we were on a research trip for jari songs in the village of Pachhaar located in Kendua Thana in the district of Netrokona - that Mir Mosharrof Hossain's famous novel 'Bishadh-Shindhu' has been performed by jari musicians in and around the area for the last 50 years.

In Netrokona, 'Bishadh-Shindhu' is used in jari songs mainly during competitions. When this happens, two boyatis question one another about the stories of the novel, answering in turn. When a boyati fails to answer a question, he loses out. During the question-answer session, the boyatis sing the disha. After that come the songs of devotion. A round of chutki follows, giving way to the questions and answers. The director of the jari troupes, Diana, does a commendable job of coordinating the artistes.

Till 1950, rhythmic storytelling from the middle ages and modern times like 'Jongonama' and 'Shahid-e-Karbala' were the norms for jari sessions. However, since 1964-65,, Netrokona's Kendua Thana and its surrounding areas have had included modern literary pieces like the 'Bishadh Shindhu' in their jari repertoire. In jari sessions, this is done in 2 different ways: by interpreting the lore into a rhythmic form or by the previously described method of question-answers.

When asked about the use of 'Bishadh-Shindhu' in jari sessions in rural areas, boyati Abdul Hashem Shorkar said, “There are 61 jari songs based on 'Bishadh Shindhu'. Of these, 26 are based on the Muharram period, 30 are based on the rescue and 5 are about the defeat of Ezid.

On the subject of Mir Mosharraf Hossain's 'Bishadh Shindhu', Helim Boyati, a famous singer from Netrokona, said “Previously, the 'Jongonama' type of jari songs were more popular in the area. Johuruddin Shorkar, Israil Boyati, Khaguria's Nobi, Bonerogati's Iman Ali, Khabashat's Kitab Ali etc. would all perform songs based on the 'Jongonama'. Then, in 1964, we pondered and realized the performance of jari songs based on the 'Bishadh-Shindhu'. All of our mentors were not alive at the time, but some of them like Ali Hossain Baul, Johuruddin, Israil etc. lived to see the performances.”

How did you begin to compose jari songs from the 'Bishadh-Shindhu'? To this question, Helim Boyati answered We first had to translate the book. Then, we converted the sentences into rhyme and manipulated the words to fit; as in, we converted the literature into poetry. We sing the songs by adding music to this poetry.

Q. But why did you turn the 'Bishadh-Shindhu' into poetry?

A. The initial intention was to make it suitable for the ears of the audience. In music form, the audience enjoys the literature a lot more. In order to add music to it, we had to edit quite a bit of the original text. Mir Mosharraf Hossain had not intended his work for musical purposes. We composed and added the music.

Q. Could you give examples of types of rhythm?

A. Here's an example of a 4-beat rhythm:

Hussain shaje donka baaje oki baaje Murari

Daine bandha dhal torowal baame bandha teer

Hajare hajare kaate go Allah Kaferero sheer

Another type of rhythm, called a 'Lohor', goes:

Amar keu nai re ei shongshaare

Thakle ki aar kandi ami Karbalar prantore

Kande kande Imam Hossain mrittikae poriya

Kande kande Imam Hossain nirostro hoiya

Kande kande Imam Hossain uthaiya dui haat

Kobul koro amar dukkho maboot monajaat

Yet another type is the tri-beat:

Are dhormoshakkhi koriya Mabia gelen kohiya

Shuno nobi shuno diya mon

Amari ouroshe giya Ezid jodi jae jonmiya

Bibaho aar korbona jibone

Stree much dekhbona tai Ajker protiggae jai

Shakkhi rakhi Aloshna Shai

Nobi bole Mabia Shuno shuno korno patiya

Amon kotha bolio na bhai

Khoda jaha gechhe koiya Tahai jabe rotiya

Tomar moto loke amon bola nai.

This is how a tripodi, or tri-beat song is done. This is a very melancholy song. When people hear this, they get goose bumps. However, the most popular type of jari is the poyar. We inject different tunes into the songs to mix it up. This is the art belongs to the master poets of boyatis. Omuk Shorkar created today's jari after mixing half a dozen tunes together. His poetry demands a certain respect. However, there is no fixed rule that we would have to employ a certain beat for a certain song.

Shuniya Kashemer kotha Shokhinae bhangilo matha

Kande bibi matite poriya

Shokhinae bole dakiya Shono he Kashed daraiya

Boli kotha dupaye dhoriya

When Kashem returns from the war, we sing-

Haere Shokhina kaade amar keho nai

Age moilo chachaji pachhe moilen bhai

Nalish dibo kar kachhe foiraader jaga nai.

These lines are a mixture of melancholy and effect. For this, the music changes. This is sung the 25th melody during the Muharram episode. These lines are a mixture of melancholy and effect. For this, the music changes. This is sung the 25th melody during the Muharram episode.

Abul Kashem juddho hoite eleno phiriya

Boli kotha ehon shomoe shoneno boshiya

Ghora hote Shokhinar buke porilen jhapaiya.

Haere Shokhina kaade amar keho nai

Abar jokhon arekjon juddhe jaitachhe tokhon gai

Bataashe bataashe pran hoe na re sheetol

Kafere ghiriya rakhchhe Forot nodir jol

Hae re nodir pani kore tolmol.

The reason for this is to put pain and peace in their own places.

This disha is used through melodies 24 through 26. We call this a dohar. However, illiterate rural people are often against these tunes and want us to change them.

Q. Who makes the dishas of the jari songs?

A. We make them. We have been making them since the days of 'Jongonama' and 'Shahid-e-Karbala'. In the old days there were fewer dishas, but we made some more. For example, we sing a dohar when the child of Imam Hossain is brought from Karbala:

Dekhe jaa re chondro shurjo nokkhotre miliya

Kande go mae mora putro loiya

Dekhe ja re chondro shurjo dakchhi toder dakiya

Ma hoiya dakchhi toder dekh na dukkho chahiya

Kande go maye mora putro loiya.

This is a disha that we composed. After this, the dohars take over, followed by the boyatis with the main words of the jari.

For example, when Hossain's family is bound or when Hossain's two kids are bound, we add a dohar:

Bandher chote chhatti phaate

Pani deo re khai

Haate bondhon khule dao

Jononir kule jai.

Re kaferer dol

Toder bujhi doya maya nai

Kande kande Joynal Abedin bandate poriya

Shait hajar lok harailam Karbalae ashiya

Shaat din noe raat gelo gujariya

Pani chhara bandhile jorete koshiya.

This is an excerpt from the jari songs based on the 'Bishadh-Shindhu'. This is appropriate when Ezid imprisons Imam Hossain and his family. This is a hurtful portion. This is a monologue by Joynal Abedin. It describes the anguish felt by him. This is how we mix the dialogues of the characters with music.

Q. Comment on the music used in jari songs.

A. We sing poyars, tri-beats, quad-beats, khemta beats, etc. We add the tunes of other poets and composers too. Mir Mosharraf Hossain was not a poet, but a writer. The jari committee does not recognize him as a poet. His writing is like a stone inscription and we cannot make changes in the content. However, the order of events cannot always be maintained. As long as the gist is maintained, we are safe.

Q. Do you follow any code or format when adding rhythm to the 'Bishad-Shindhu'?

A. We have to maintain a certain code. In our language, poetry is of a certain type. For example, we say:

Hoy moy roy joy noy choy roy shoy

Jahar mil roe tahakey kobitto koe.

In one word whoever can rhyme is a poet.

There is a misconception in our country that rural culture has nothing to do with written culture. However, after seeing Mir Mosharraf Hossain's 'Bishad-Shindhu' in jari form in Netrokona, our minds were cleansed of this. Instead, what we learnt from these musicians, the skill and aptitude we witnessed, opened our eyes and made us realize that there is a lot left for us to discover about the origins of Bangladesh's folk traditions.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009

|

JARI songs are one of the popular branches of traditional performing arts of Bangladesh, which are the backbone of the country's folk arts. On the 10th of Muharram, in the 61st year of the Islamic calendar, Imam Hossain, the grandson of Islam's last Prophet Muhammad (SAW), was martyred brutally alongside his family at Karbala, Iraq. Bengali Muslims, who based them on the martyrdom of Imam Hossain, composed jari songs. Although the songs were initially only based on these events, their popularity caused the inclusion of other stories into the genre. The poet Jasim Uddin did extensive research on the subject and included in his repertoire not only the usual jaris about the events in Karbala, but also about the baptism of Mecca, the exile of Hajera, Kurbani, Yousuf, Kulsum's Mezbani, Anaal Haque etc. However, on the 25th of May 2009, we learned something new while we were on a research trip for jari songs in the village of Pachhaar located in Kendua Thana in the district of Netrokona - that Mir Mosharrof Hossain's famous novel 'Bishadh-Shindhu' has been performed by jari musicians in and around the area for the last 50 years.

JARI songs are one of the popular branches of traditional performing arts of Bangladesh, which are the backbone of the country's folk arts. On the 10th of Muharram, in the 61st year of the Islamic calendar, Imam Hossain, the grandson of Islam's last Prophet Muhammad (SAW), was martyred brutally alongside his family at Karbala, Iraq. Bengali Muslims, who based them on the martyrdom of Imam Hossain, composed jari songs. Although the songs were initially only based on these events, their popularity caused the inclusion of other stories into the genre. The poet Jasim Uddin did extensive research on the subject and included in his repertoire not only the usual jaris about the events in Karbala, but also about the baptism of Mecca, the exile of Hajera, Kurbani, Yousuf, Kulsum's Mezbani, Anaal Haque etc. However, on the 25th of May 2009, we learned something new while we were on a research trip for jari songs in the village of Pachhaar located in Kendua Thana in the district of Netrokona - that Mir Mosharrof Hossain's famous novel 'Bishadh-Shindhu' has been performed by jari musicians in and around the area for the last 50 years.

These lines are a mixture of melancholy and effect. For this, the music changes. This is sung the 25th melody during the Muharram episode.

These lines are a mixture of melancholy and effect. For this, the music changes. This is sung the 25th melody during the Muharram episode.