| Cover Story

From Insight Desk

Where Royal Bengals Tread

The Sundarban forest is the world's largest mangrove forest, which stretches from Bangladesh to India. It was declared a RAMSAR site in 1992 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997. The forest is almost 10000 sq. km in area, and 62 percent of it falls within the territory of Bangladesh. Given its rich biodiversity and the unique ecosystems that lie within the forest, the ecological and environmental importance of the forest is immense. This cover story of this fortnight's Star Insight presents a travelogue of Sundarban forest

...........................................................................................................

Zahidul Naim Zakaria

I wasn't quite sure when our small ship would make its way into the Sundarban forest, but as the scenery on the two sides of the ship changed and human settlements became harder and harder to find, I knew we were getting closer. I was sitting in the dining room of the M.V. Aboshar, a cruise ship of the Guide Tours Ltd, who arranges trips to the Sundarban forest. My question was answered by a rather large dragonfly that flew in and landed on top of my laptop screen and a wild rooster whose crow sent a rift through the serenity of the natural habitat. We were there.

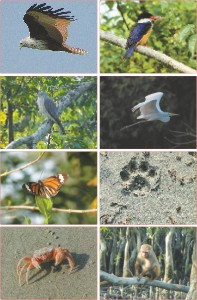

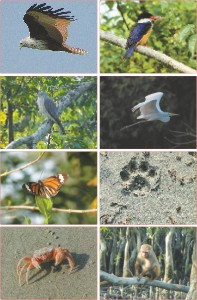

We headed out into the forest in a small houseboat at the crack of dawn, and in the wilderness we found various birds such Herons, Cuckoos, Egrets, many Brahminy Kites, a Crested Serpent Eagle and a Black-capped Kingfisher. We were lucky enough to even see a monkey, a lizard and a couple of spotted deer. We had to remain as quite as possible, so that we don't scare the animals and birds away beyond our line of sight. Every time we spotted an animal, our houseboat became jittery with awe as our faces lit up in soundless excitement! The only audible sounds were the gentle rustling of the trees, the slow rowing of the boat, and the artificial click of our digital cameras. In our minds, we were asking ourselves the same question, “Will we be lucky enough to see a Royal Bengal Tiger?” The natural beauty of the forest was fascinating. Observing how the trees grow in unison to one another, and how the bird and animals make their home in their midst was an amazing experience, one that city dwellers seldom have the opportunity to appreciate. And this was only at the edge of the forest, at its periphery; we could only imagine what lay at the forest's womb. Although we were out in the wild, there was a sense of calm in the air and in all of us. The forest seemed anything but wild, it was rather where the wilderness still survived, far from dense human settlements, untouched and unadulterated by human interests and activity.

The Sundarban forest is the world's largest mangrove forest, which stretches from Bangladesh to India. Its name literally translates into 'Beautiful Forest', and most people agree that the name is derived from 'Sundari' trees (Heritiera Fomes) which are most common throughout the forest. Although mangroves are defined as trees that grow in saline waters, mangroves actually can grow in both saline and fresh waters; they simply find it easier to grow in saline waters where there is less competition for space since common trees are not saline-resistant, reports Wikipedia. The forest is almost 10000 sq. km in area, and 62 percent of it falls within the territory of Bangladesh. Given its rich biodiversity and the unique ecosystems that lie within the forest, the ecological and environmental importance of the forest is immense. It was declared a RAMSAR site in 1992 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997. According to the Forest Department, the Sundarban forest is home to 334 plant species, more than 375 fauna species; 375 wildlife species that habituate the Sundarbans include 35 reptiles, 315 birds, 42 mammals including the Royal Bengal Tiger. In 2004, a census of tigers estimated the existence of 440 tigers including 298 female, 121 males and 21 cubs in the Sundarbans. The forest is a labyrinth of tidal waterways, mudflats and small islands of salt-tolerant mangrove forests. The interconnected network of waterways makes almost every corner of the forest accessible by boat. The Sundarban forest is the world's largest mangrove forest, which stretches from Bangladesh to India. Its name literally translates into 'Beautiful Forest', and most people agree that the name is derived from 'Sundari' trees (Heritiera Fomes) which are most common throughout the forest. Although mangroves are defined as trees that grow in saline waters, mangroves actually can grow in both saline and fresh waters; they simply find it easier to grow in saline waters where there is less competition for space since common trees are not saline-resistant, reports Wikipedia. The forest is almost 10000 sq. km in area, and 62 percent of it falls within the territory of Bangladesh. Given its rich biodiversity and the unique ecosystems that lie within the forest, the ecological and environmental importance of the forest is immense. It was declared a RAMSAR site in 1992 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997. According to the Forest Department, the Sundarban forest is home to 334 plant species, more than 375 fauna species; 375 wildlife species that habituate the Sundarbans include 35 reptiles, 315 birds, 42 mammals including the Royal Bengal Tiger. In 2004, a census of tigers estimated the existence of 440 tigers including 298 female, 121 males and 21 cubs in the Sundarbans. The forest is a labyrinth of tidal waterways, mudflats and small islands of salt-tolerant mangrove forests. The interconnected network of waterways makes almost every corner of the forest accessible by boat.

Over 3.5 million people live in the Sundarbans' Ecologically Critical Area (ECA), with no permanent settlement within the Sundarbans Reserve Forest. Of them, about 1.2 million people directly depend on the Sundarbans for their livelihoods. Most of these people are Bawalis (wood cutters/golpatta collectors), fishermen, crab and shell collectors, Mawalis (honey collectors) and shrimp fry collectors and mostly women and children. Cyclone Sidr in 2007 caused tremendous disruption to natural habitats and brought death to man and wildlife alike at the coast of Bangladesh, including the Sundarban forest.

News of tiger attacks on villagers and their livestock did keep us a bit on edge. On one hand, we were very excited to see a tiger, but what were we to do if we found ourselves in close confrontation? On average, 15-25 people are killed in tiger attacks every year, according to the Forest Department. But, most people agree that this is an underestimation since most deaths go unreported. Last year, after a Royal Bengal Tiger strayed into Abadchandipur village adjacent to the Sundarbans in Shyamnagar upazila in search of prey, it was beaten to death by villagers.

Photo by Emile Mahabub

According to World Wildlife Foundation (WWF), there are around 3,200 tigers in 14 Tiger Range Countries (TRG) of the world. In 1900, there were a hundred thousand tigers! Wildlife protection agencies and activists term the Sundarbans the most intense human-tiger conflict zone. In 2010, in a joint training event on tranquilizers under the Tiger Action Plan (2009-2017), speakers said that in 2009 alone, tigers killed 51 people in time to time so that tigers could prey on them. The plan was to reduce their interest in straying into the villages. The government of India agreed to subsidize the programme with the motive of reducing conflict between man and tigers of Sundarban. Ale and Whelan (2009) observes that, as the top predator, the tiger may help to regulate the number and distribution of prey, which in turn will impact forest structure, composition, and regeneration. Hence the loss of tigers may reduce ecosystem integrity and ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions. We cannot ignore our fascination with tigers! We simply love big cats. And the Royal Bengal tiger is a large part of our national identity; it is embedded in our culture and acts as the flagship species that draws public support for conserving an entire ecosystem. Without the tiger, the Sundarban cannot be sustained.

Bangladesh while three tigers were killed in different adjoining areas of Sundarbans. In 2008, local villagers in India agreed to release goats and cows in the forest from time to time so that tigers could prey on them. The plan was to reduce their interest in straying into the villages. The government of India agreed to subsidize the programme with the motive of reducing conflict between man and tigers of Sundarban. Ale and Whelan (2009) observes that, as the top predator, the tiger may help to regulate the number and distribution of prey, which in turn will impact forest structure, composition, and regeneration. Hence the loss of tigers may reduce ecosystem integrity and ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions. We cannot ignore our fascination with tigers! We simply love big cats. And the Royal Bengal tiger is a large part of our national identity; it is embedded in our culture and acts as the flagship species that draws public support for conserving an entire ecosystem. Without the tiger, the Sundarban cannot be sustained. Bangladesh while three tigers were killed in different adjoining areas of Sundarbans. In 2008, local villagers in India agreed to release goats and cows in the forest from time to time so that tigers could prey on them. The plan was to reduce their interest in straying into the villages. The government of India agreed to subsidize the programme with the motive of reducing conflict between man and tigers of Sundarban. Ale and Whelan (2009) observes that, as the top predator, the tiger may help to regulate the number and distribution of prey, which in turn will impact forest structure, composition, and regeneration. Hence the loss of tigers may reduce ecosystem integrity and ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions. We cannot ignore our fascination with tigers! We simply love big cats. And the Royal Bengal tiger is a large part of our national identity; it is embedded in our culture and acts as the flagship species that draws public support for conserving an entire ecosystem. Without the tiger, the Sundarban cannot be sustained.

Later in the day with Forest Guards in our company, we went to Jamtola, where the enchanting beauty of the wilderness captivated us once more. We traipsed from the Observation Point at Jamtola towards Kotka beach and snapped away at the flora and fauna of the Sundarban forest. We were also lucky enough to spot an entire herd of chital deer. We were not lucky enough to see a Royal Bengal Tiger, but we did see paw prints on the sand at Kotka beach. This was the most exciting part of our journey, as the Forest Guard informed us that the paw prints were fresh, they were between 12 and 8 hours old. They were certain of this since paw prints on the sand don't remain very definitive for too long, since the sand is blown away by wind easily. We were standing at the very spot where a Royal Bengal Tiger had walked by, perhaps on a leisurely early morning stroll. We were standing where Royal Bengals tread.

Photo by Emile Mahabub

Tourists should keep in mind that they have a responsibility to leave the forest as they found it; they need to minimize their influence on the natural habitat so that it is protected. With that sense of respect in mind, urbanites should take the time out of their regular lives to visit such natural treasure troves of the world and witness the charm and wonder that lay within. As my father had told me, it's only after visiting such a green haven of oxygen that you see your home in Dhaka for what it really is - a prison of bricks which you've locked yourself in.

Photographs by Zahidul Naim Zakaria

(unless otherwise mentioned)

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2009

|

|

The Sundarban forest is the world's largest mangrove forest, which stretches from Bangladesh to India. Its name literally translates into 'Beautiful Forest', and most people agree that the name is derived from 'Sundari' trees (Heritiera Fomes) which are most common throughout the forest. Although mangroves are defined as trees that grow in saline waters, mangroves actually can grow in both saline and fresh waters; they simply find it easier to grow in saline waters where there is less competition for space since common trees are not saline-resistant, reports Wikipedia. The forest is almost 10000 sq. km in area, and 62 percent of it falls within the territory of Bangladesh. Given its rich biodiversity and the unique ecosystems that lie within the forest, the ecological and environmental importance of the forest is immense. It was declared a RAMSAR site in 1992 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997. According to the Forest Department, the Sundarban forest is home to 334 plant species, more than 375 fauna species; 375 wildlife species that habituate the Sundarbans include 35 reptiles, 315 birds, 42 mammals including the Royal Bengal Tiger. In 2004, a census of tigers estimated the existence of 440 tigers including 298 female, 121 males and 21 cubs in the Sundarbans. The forest is a labyrinth of tidal waterways, mudflats and small islands of salt-tolerant mangrove forests. The interconnected network of waterways makes almost every corner of the forest accessible by boat.

The Sundarban forest is the world's largest mangrove forest, which stretches from Bangladesh to India. Its name literally translates into 'Beautiful Forest', and most people agree that the name is derived from 'Sundari' trees (Heritiera Fomes) which are most common throughout the forest. Although mangroves are defined as trees that grow in saline waters, mangroves actually can grow in both saline and fresh waters; they simply find it easier to grow in saline waters where there is less competition for space since common trees are not saline-resistant, reports Wikipedia. The forest is almost 10000 sq. km in area, and 62 percent of it falls within the territory of Bangladesh. Given its rich biodiversity and the unique ecosystems that lie within the forest, the ecological and environmental importance of the forest is immense. It was declared a RAMSAR site in 1992 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997. According to the Forest Department, the Sundarban forest is home to 334 plant species, more than 375 fauna species; 375 wildlife species that habituate the Sundarbans include 35 reptiles, 315 birds, 42 mammals including the Royal Bengal Tiger. In 2004, a census of tigers estimated the existence of 440 tigers including 298 female, 121 males and 21 cubs in the Sundarbans. The forest is a labyrinth of tidal waterways, mudflats and small islands of salt-tolerant mangrove forests. The interconnected network of waterways makes almost every corner of the forest accessible by boat.

Bangladesh while three tigers were killed in different adjoining areas of Sundarbans. In 2008, local villagers in India agreed to release goats and cows in the forest from time to time so that tigers could prey on them. The plan was to reduce their interest in straying into the villages. The government of India agreed to subsidize the programme with the motive of reducing conflict between man and tigers of Sundarban. Ale and Whelan (2009) observes that, as the top predator, the tiger may help to regulate the number and distribution of prey, which in turn will impact forest structure, composition, and regeneration. Hence the loss of tigers may reduce ecosystem integrity and ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions. We cannot ignore our fascination with tigers! We simply love big cats. And the Royal Bengal tiger is a large part of our national identity; it is embedded in our culture and acts as the flagship species that draws public support for conserving an entire ecosystem. Without the tiger, the Sundarban cannot be sustained.

Bangladesh while three tigers were killed in different adjoining areas of Sundarbans. In 2008, local villagers in India agreed to release goats and cows in the forest from time to time so that tigers could prey on them. The plan was to reduce their interest in straying into the villages. The government of India agreed to subsidize the programme with the motive of reducing conflict between man and tigers of Sundarban. Ale and Whelan (2009) observes that, as the top predator, the tiger may help to regulate the number and distribution of prey, which in turn will impact forest structure, composition, and regeneration. Hence the loss of tigers may reduce ecosystem integrity and ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions. We cannot ignore our fascination with tigers! We simply love big cats. And the Royal Bengal tiger is a large part of our national identity; it is embedded in our culture and acts as the flagship species that draws public support for conserving an entire ecosystem. Without the tiger, the Sundarban cannot be sustained.