| Story

Waiting for the ferry

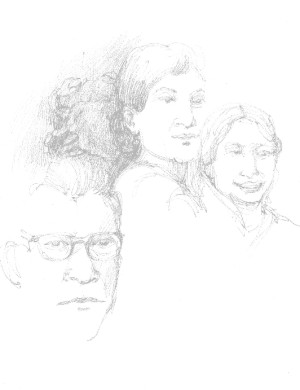

Syed Shamsul Haque

Syed Shamsul Haq was born in a small town called Kurigram (now a district town) on December 27, 1935. His father was Syed Siddique Husain, a homeopathic physician, and his mother was Halima Khatun. Haq passed his childhood in Kurigram. During his childhood he observed the harshness of the Second World War. Haq is married to Dr. Anwara Syed Haq (also an outstanding writer in her own right). He is father to a daughter, Bidita Sadiq and a son, Ditio Syed Haq. Syed Shamsul Haq writes poetry, fiction, plays- mostly in verse and essays. He is recognized as one of the leading poets of Bangladesh. His experiments with forms and the language have given a new direction to Bangla literature.

Continued from last issue…

I am tensed. I think my thoughts are futile. I cannot fathom the reason behind my thoughts. I notice that the man has now stopped. I see a woman, maybe 25 to 27 years old, clad in a white saree, exiting a car. She has a very small child with her. A girl. Holding her mother's finger she is circling her with her childlike steps. The husband exits the car as well, lights a cigarette and starts to observe the river, the people, and the crowd. He's checking his watch frequently.

The woman is stooping down to hold her child. The child is getting out of control every time. And the woman's cloth covering her chest is falling off every time. Her breasts become obvious every time she stoops down. But she is in no hurry to pick up her aachol. And the child is laughing. And each and every time she is tugging at the corner of the fallen aachol and laughing. She is not at all concerned about how visible her features are becoming! Who knows if her pride comes from being a new mother or because of her overflowing youth!

The man's a great pervert! I see him go and stand right next to her. I see him looking at her once and the child next with piercing eyes. And I see myself standing right next to them.

The steaming heat of the day has made the woman sweat. I think sweat contains salt. Streaks of white have formed near her underarms. This is not today's sweat. How many days has it been since she washed the cloth? She had put on heavy make-up on her face. It's all melted away now. All the eyeliner, lipstick and powder have mixed and blended together in a haphazard manner. A fly is buzzing near her cheek. Maybe it's because of the strong perfume she has put on. The husband is staring at her with a trance like look.

I turn my gaze away. I move away a little with indifference. The man moves away too. He keeps on rating and comparing with an extended neck from far. Then he walks off to a far-faring bus. I keep observing him from my spot.

Even so, the apparitions of the woman's wet underarms from all the sweat and her makeup dumped pale face keeps bombarding my mind. I want to erase the picture. I can't. I keep shifting my impatient gaze from the woman to the man.

In just an instance while I was shifting my glance from the woman to the man, I see that he is gone. Where did he disappear? He was here right now! I keep searching for him in the crowd frantically. No, I am not running. I keep searching for him with my eyes. I can't find him. I start to move away slowly. I pass the woman once more while moving away.

I can hear the husband berating the woman in a hushed voice. He is scolding her in an enraged voice, “You've gone far enough! Lost all your senses! Come sit in the car!” The wife doesn't care. She says, “You go sit in the car. I'll enjoy the river wind.”

“There is no end to your wants!”

“Shut up!”

“You shut up! Take care of your bosom!”

“You check your gaze! Such things will happen during journeys.”

Journey, journey, journey. I keep repeating the word in my mind.

I have journeyed a lot with my wife. Dhaka to Jhenidah. Dhaka to Tangail. Dhaka to Comilla-Chittagong. She needed nothing more while vacationing. She would see the world to her heart's content. I cannot afford to go to Bangkok or Singapore. So within the country it is. Maynamati, Mujibnagar, Paharpur, the sea, the tea gardens.

But she had great fear of journeys. She would always say prayers before heading off from the house. She would bring along a whole roll of toilet-paper in her handbag, “Who knows where you might need to go during the journey! Where is the guarantee that you will find toilet paper!” She would even carry four or five water bottles, “What if you contract diarrhea from drinking water from the streets!” On top of that she would always wrap the aachol all around her to cover her body, “Oh no! The looks strangers give you on the road are very bad!”

“So what! They're strangers! So what if they look!” “So what! They're strangers! So what if they look!”

“Not everyone is like you! One who is shamed to look at his own wife!”

I am able to tell the reasons for my concerns now. Why I was not liking that man. It was because of him that I have looked upon things that I would never even glance upon.

Am I then turning into a pervert after so many days, today, by this river, waiting for the ferry in the crowd? I too am staring at the jeans clad girl, the woman with the sweaty underarms like a pervert!

I am certainly watching! I have seen them. I have leered at them. I have seen them in and out.

I remember my wife, “My love, you won't look at any other after I am gone, will you?”

The man falls into my sight once more. He is coming down from the bus. Writings on the front of the bus say Dhaka-Meherpur. I have been to Meherpur with my wife as well. Visited Mujibnagar, under Shiva's tree where the head of Independent Bangladesh was sworn in.

A void spreads through in my heart. I start walking like a destination-less vagabond. I notice the swarm of women on the bus. One of them is sticking her head out the window and vomiting. Yellow rice is spewing out. Poor thing, she must have had too much rice before heading out from home.

Two teenage girls from the village are sitting petrified by another window. The hair on their heads is plaited into pony tails soaked in oil. Each is embracing the other on looking the world around them.

An old woman is protruding her head out of another window and spitting out her chewed betel leaf. The spittle is rolling down the side of the bus.

I suddenly see the man coming by the window and standing there. He starts scolding the old woman next.

“Maa, the spit will hit passengers! Look what you're doing to the bus as well! Be careful while spitting.”

“You and your carefulness! Do you even look after me in my old age? What else do I have in this world besides my betel leaves? Keep a look out for chewing tobacco. Mine's all gone.”

The man started scolding her with twice the rage, “You've got one foot in the grave, yet, your craving for tobacco doesn't go.”

“Death! You try to scare me with the name of death?” the old woman starts laughing hysterically.

The man, enraged even more, started saying, “I'll bring you your tobacco to your grave. Don't you worry.”

The old woman's gaze shifts to me next. She says, “Did you see and hear the ingrate's words? I gave him milk from this bosom, I looked after him while growing up.”

The man retaliates saying, “For how much longer will you emotionally poke me referring to the milk from your breasts? They're all dried up now!”

The old woman is enraged. She starts yelling after nearly crawling the whole of her thin body through the window, “Son of the cursed, this chest still has milk. The whole of the world won't be able to suck it dry, so much of milk! But you are you! Ingrate the son of ingrate! I can give milk to a thousand more to the likes of you!”

The old woman then stands up with her head straight shoving the window aside. She then removes her shawl from above her chest and shows the world. I see it too. A dead bosom. The bosom of a mother from ages past. The slightest hint of breasts are no more on that chest. The cheap green blouse is fluttering with emptiness.

The man looks at me suddenly. This is the first time he speaks to me.

“Maa's not right in the head, you know. It's an illness since long.”

All the energy saps out of me hearing this. I slowly retreat step by step.

I hear the man speaking to her in a softer tone, “Maa, cover you bosom. Cover it. All your sense of shame has been depleted as you've grown older. Put the shawl back on. The world is watching.”

The world gets publicized. The world watches on. The little girl's mother returns to the car and sits down. The young girl, leaning against the pillar, stands upright and pulls down her shirt to loosen it. The humming sound of the ferry carries over from the breast of the river.

I remember that this is the first time that I have ever taken the car out alone on a journey. Alone. Just me. I don't have my wife with me today. This is the first time she's not with me. My wife passed away 39 days back from breast cancer. It's her challisha tomorrow. I am visiting my in-laws. Her challisha will be held at their house. I have no children. She had given me her bosom; she was not lucky enough to have given it to her child.

Translated by Hasan Ameen Salahuddin

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2011

|