|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Community policing: Our experience

Muhammad Nurul Huda

Community Policing is a vague phrase that has become a vogue one. Inside police circles, it is too often seen as a soft option. Even as it grows fashionable in enforcement parlance to restore good relations with the community, many sceptics keep asking what effect the so-called Community Policing will have on the issues that dominate the headlines regularly-rising crime figures, drug abuse and the regular outbreaks of public disorder.

It is a universal fact that quite apart from their dominant role in crime prevention and maintenance of law and order, the public also provide the necessary information on the vast majority of cases which lead to prosecutions and convictions. This flies in the face of police efficiencyculture where Community Policing is not seen as 'real policing' and also in the mythology of police fiction in which detectives are portrayed as heroes.

Conventional policing is considered inadequate for the task of conflict resolution ranging from domestic to full scale public order problems. The police in their fighting mode are uncomfortably inappropriate agents of peace and understanding. The community itself needs to play the leading role in dealing with conflicts and thus understanding police reactions and actions in a thoughtful and considered way that can promote non-violent solutions and at times accommodation between conflicting parties.

We all need to pay due respect and accord recognition to the cunning, skill and courage to mediate and defuse conflict situations before they reach the boiling point. This respect has to be part of the new ethos of police as against the dominantly prevalent hard policing practices.

The above involves a wider grasp of community dynamics. There is perhaps no such thing as a single homogenous community. Each interest group can either be a source of support or disturbance, depending on how they see themselves in relation to the rest. We all know that crude policing can escalate small problems into big ones while discreet policing aimed at conflict resolution can promote an atmosphere of tolerance in a potentially volatile situation.

The concept of Community Policing is based on the belief that conflict resolution is a long term matter in which notions of equity, fairness and community justice must be developed by all groups involved. The principles of conflict resolution have become significant now that the failures of the criminal justice system to achieve law and order through punishment are all too evident. There is an appreciation of promoting the idea of justice in the community.

The Bangladesh experience

The oldest form of organised public initiated community policing in Bangladesh goes back to the Panchyaet system of early 19th century in Dhaka, and the oldest form of govt. initiated organised community policing dates back to the introduction of 'Chowkidars' and 'Dafadars' of the late 19th century. The Panchayets in old Dhaka is a classical example of 'neighbourhood' policing. It is still functioning in some neighbourhoods of old Dhaka and has been playing the central role in resolving local conflicts, maintenance of social order and social cohesion. The 'Chowkidari' system played a significant role in bringing back order from the chaotic situation prevailing in the 1860s. However, the role of Chawkidars began to fade away after the independence of Bangladesh. Surprisingly, a similar system of policing called Chauzisho (one-man police station like one-man Chawkidari system) has eventually evolved as the backbone of Japanese police system. The Chauzisho alone make 77% arrests in Japan. Chowkidars were not only the extended hands of formal police in respect of rural policing but also the main agents of criminal and political intelligence during the British and later Pakistan regimes.However, Community Policing in the context of our time was first introduced in Mymensingh town in 1992 with the name of Town Defence Party and in a few parts of Dhaka city in 1993 with the name of “Protibeshi Nirapatta" (neighbourhood watch). As it implies, the strategy adopted a wider perspective of crime prevention and conflict resolution. Since its introduction the command areas witnessed visible improvements in crime scenario and remarkable reduction in fear of crime.

In the context of Dhaka City, COP or partnership with the community is something like “extra eyes and hands of police.” Given the scarcity of police manpower, the police perspective of COP is getting more and more private watchmen and women i.e. getting more public hands and eyes in patrolling and watching neighbourhoods and beats.

This partnership is tangible; as the community engagement is physically visible i.e. police practically feel the sharing of responsibility. In the pursuit for combating major street crimes in the Tejgaon industrial area local police thought about taking stock of private security guards. The finding was interesting; there were as many as 350 private guards in the Tejgaon industrial area -- 16 times bigger than strength of the Tejgaon police outpost. The finding gave Tejgaon police a different direction i.e. “redirecting' the role. The outpost normally gets only 6-7 officers and men to perform a shift but by integration, coordination and supervision of the private guards, 'virtual police' manpower could be increased to more than hundred per shift. The 'redirected' police role created a mirror effect i.e. a transfer of power place from police to private guards, in other words private guards became “Virtual Police.”

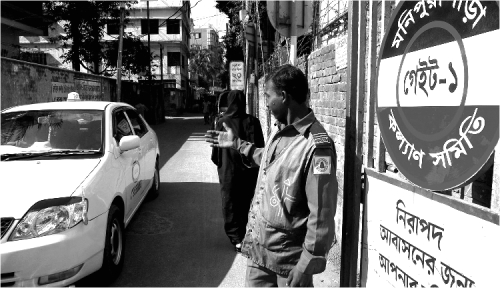

Residential neighbourhoods are much more dynamic than the industrial pockets, and as such-police-public partnership has got to be deeper. Regular communication between the community and the police is like a routine matters because day to day problems are unique and so are the problem solving processes. As the neighbourhoods are unique in character, so are the responses to their needs. Problem-solving is a major element of COP. Lalmatia and Pisciculture Housing Society solved the problem of mugging by transforming the neighbourhoods into “Gated Communities,” whereas Monipuripara solved their problem of traffic congestion by enforcing “one ways.” During the Ramadan and Durga Puja, police is now seen as bargaining with community leaders about the number of volunteers they can engage with police for joint watch or patrolling.

Another dimension of COP in urban neihbourhoods is the pursuit for creating “safe heaven” by securing 24 hours X seven days. This was necessitated by the increasing number of criminal acts during day time. However, the 'safe heaven' concept also required 24 hours police presence and a number of other initiatives to prevent infiltration of criminal elements. A few such measures are: establishment of community police posts, issuing identification sticker for vehicles of residents, ID cards for hawkers etc. Monipuripara, Lalmatia Housing Society, Pisciculture Housing Society are only a few such successful initiatives. In Dhaka city there are now more than hundred successful neighbourhood watch initiatives under COP scheme, some have passed a successful decade. Up until now government participation in the initiative is far less than expected, though lately there has been visible changes in the police level outlooks about the matter. In the face of recent terrorist activities, DMP has started community profiling through home visit programmes.

If we sum up the essence of COP what do we see in police community partnership initiatives in Dhaka? Briefly, these are, opening up and establishing one or more communication channels between the police and the communities, decentralisation of authority to both the subordinate ranks of police and to the community members, delegation of power to the lower ranks, empowerment of the communities as the co-producer of policing services, joint problem solving, 24 hours security etc.

Points to ponder

Police forces have a vested interest in maintaining good public relations. Community liaison should not therefore be simple a peripheral function, but one of the main central roles of every police officer. As such it should comprise a major part of the training and job specification of all officers.Good community relations depend on reciprocity, power-sharing and collaboration. In this context, too, the “community” cannot just be seen as the conforming and the participating, but must be understood to include the activists and the detached members, to reach whom will require a more dedicated effort.

Although police forces can, and should, play a role in fostering community peace, they cannot be expected to overcome the effect of widespread discrimination, sense of injustice, social disadvantage and group alienation. Although the police may on occasion make mistakes that can trigger off major incidents (they are human, which is a positive attribute), they cannot be held to blame for the sense of grievance and despair that fan the flames into a full-scale conflagration.

The police role in promoting Community Policing requires them to see law and order in a new perspective, not just as a lull in which the Walkie-Talkies are quiet but as a definite objective to be wished devoutly.

....................................................

The author is former secretary & IGP.