|

||

Pakistan's post-71 generation

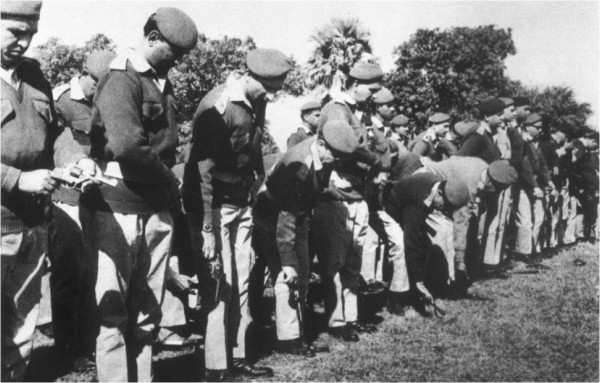

Shahedul Anam Khan This time it was interesting to sense also the great inquisitiveness on their part to know what exactly had happened in 1971. Successive Pakistan governments after 1971 projected the events of 1971 in a manner that painted the birth of Bangladesh as the result of a 'devious design by the Indians'. Nothing of the political developments following the 1970 elections, nothing of Bhutto's claim that there were two majority parties in one country, nothing about how the half-baked generals at the helm of affairs misread the Bengali psyche and thought that guns could quell their aspirations, ever came up for serious discourse, certainly not in school or college curricula. Even those who were too young to recall the particulars, acknowledged the very dubious attempt to keep the people of Pakistan from learning about the gruesome details of the army repression in Bangladesh. And some of the young people that I met this time felt that not enough voices were raised in Pakistan against the army action in the eastern part of the country. And they blamed the lack of information primarily for this. But they were also unanimous in their castigation of the PPP and Zulfiquar Ali Bhutto for having played the most mischievous role in forcing Yahya to cancel the National Assembly session in Dhaka. One even cited his threat to those MNAs elected from the western wing that they would not be allowed to return to Pakistan if they dared to go to Dhaka to attend Parliament. But some of them were even surprised that a country with two wings separated by almost 2000 km of hostile territory survived as long as it did. It was also interesting to be asked directly by a young man during the course of my tour whether I would give some examples of the discrimination that the people of the eastern wing had to endure. Disproportion in budgetary allocations, outlay in the five-year plans, and the very poor representation of Bengalis in the armed forces and political gerrymandering came to mind instantly. What startled me most was the next comment, "We hope you are making the most of the foreign exchange you are earning from your jute export." I was not sure whether that was a dig at how poorly we had managed the jute sector post -71 and whether the questioner was aware that the largest jute mill in the world had been closed down two years ago, or whether it was a genuine expression of goodwill. A mumbled incoherence was all that I could manage. Not surprisingly, Bangladesh evinces no great emotion and it no longer is an emotive issue to those born and brought up after 1971. But they take interest in what happens in our country. Some of them seemed to be keenly interested in the stranded Pakistanis and considered it a humanitarian issue, and, without saying in so many words, suggested that their government ought to have addressed it more sincerely, and wondered why those that expressed allegiance to their country have been discarded by their government. But there is a near unanimity on the need to enhance interaction between the two South Asian countries, some complaining that there were not enough of exchanges of young scholars, of cultural activists, and the like, between the two countries. They suggested that the two countries might think of avenues to strengthen the bilateral relationships and go beyond SAARC Charter. And, of course, the Nobel Peace prize won by Prof Yunus was a matter they took immense pride in. As for India's role in the 71 episode, the younger generation was of the opinion that the military junta of the time was too daft to see through the 'Indian game'. They felt that the leadership should not have allowed the matter to come to such a stage where the eastern wing was forced to secede. Such a reflection was quite a change given the mindset that still persists in the majority consciousness of the pre-71 generation in Pakistan to this day, that Bangladesh was an 'Indian creation'. They are quite receptive to the contrary idea that the birth of Bangladesh was a natural sequel to the concatenation of events since 1947 and for taking the Bengalees for granted. The post-1971 generation in Pakistan demonstrated keen interest in the rise of Muslim radicals in Bangladesh and their view regarding radicals in Pakistan was interesting. They made no secret of their feelings about rise of the obscurantists over the last decade, particularly after 9/11. The Women Protection bill, particularly to the young women, was a great move forward towards thwarting the political clout of the mullahs, whose rise they attributed to not only the internal political dynamics in Pakistan but also to the US policy in Afghanistan and Iraq, and more so The election victory of the MMA in NWFP solely and in Balochistan as a coalition, they felt, was not so much a vote for the Islamists as a mandate against the US. They would like to see them out not so much because of their political hue but because they have been able to deliver very little by of way economic development, and if anything, there has been more corruption in the last five years than in any period before. That the events of 1971 should never have occurred was the consensus opinion of the younger people of Pakistan that I happened to meet. Leadership folly caused it, and not learning from events of not a very distant past would be a greater folly, given Pakistan's current fight against terrorism, they felt. But at the end of it all they were one in suggesting that we should forget and forgive. There could be only one answer to that: while it is not impossible to forgive, no Bengali can forget the traumatic times of 1971. |

||