|

||||||||||||

Working democracy: A stocktaking--Dr. Kamal Hossain Politics invading culture--Serajul Islam Chowdhury Bangladesh at 40: Addressing governance challenges -- Barrister Manzoor Hasan, Dr. Gopakumar Thampi and Ms. Munyema Hasan Party government and partisan government-- Dr. Mizanur Rahman Shelley Is rule by the majority enough?-- Mohammad Abu Hena The rubric of good governance --Mohammad Badrul Ahsan For a human rights culture -- Professor Dr. Mizanur Rahman For an independent Human Rights Commission-Sayeed Ahmad Of this and that -- Sultana Kamal Tribalist corruption-- Mohammad Badrul Ahsan Fighting terrorism: Enforcement challenges--Muhammad Nurul Huda Combating corruption: People are watching-- Iftekharuzzaman E-government and its security-- Dr. M Lutfar Rahman CHT Accord: Implementation a half empty glass -- Devasish Roy Wangza Citizenship and contested identity: A case study -- Bina D'costa and Sara Hossain Forty years of "yes ministership"-- Mahbub Hussain Khan Politician-bureaucrat interface-- AMM Shawkat Ali Impartial bureaucracy: A fading dream-- Nurul Islam Anu Forty years... and diverse governments--Syed Badrul Ahsan Protect environment, save the nation--Morshed Ali Khan

|

||||||||||||

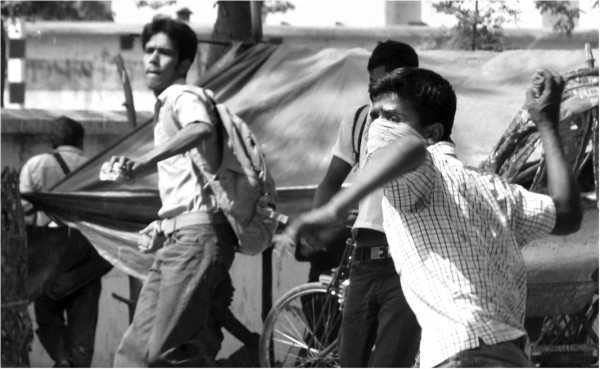

PHOTO: Iqbal Ahmed/ Drik News |

||||||||||||

Politics invading culture Serajul Islam Chowdhury Admittedly, culture is more enduring than politics; nevertheless politics has its power, and because of the power it wields politics can, and has, influence culture in Bangladesh as elsewhere in the wall. Moreover politics has the capacity to develop a culture of its own. The mainstream political culture in our country has several characteristics, among which are violence, intolerance, lack of mutual respect, and, most importantly, indifference to the well-being of the common man. None of these is congenial to the advancement of democracy. Our culture, on the other hand, does possess, despite its weaknesses, democratic values, including secularism, warm heated togetherness and responsiveness to surrounding nature. These are particularly noticeable in people's culture- in the arts, crafts, literature and even in religious festivals. The ever helpful metaphor of the river is useful here as well. We have a culture that resembles the flow of a river, adding to the creativity and unity of the nation; but has been, like our natural rivers, sadly polluted by the activities of political leadership of the country. Of the many hindrances that politics had created for culture two were of far reaching consequence, class division and communalism. The division of class has continually been widened and deepened and communalism had led to the most disastrous of the episodes in the history of Bengal after 1757, namely, the partition of the country. Politics did not belong to the common man; it was, and still is, a prerogative of the privileged middle class, devoted to the furthering of their own prospects. And the violence we notice in the political arena is rooted in the quarrel over the distribution of the national wealth in the creation of which the contribution of the ruling class has been negligible. The common man has taken part in politics, and, indeed, politics owed its effectiveness to people's participation. The reason why people lent support to the call of the political leaders was the hope that politics would bring them emancipation. But that dream has not come true. The state has altered, quite visibly in name and size, but its undemocratic and bureaucratic nature has remained more of less unchanged. This is because although we have achieved independence, not once but twice, mainstream politics has continued to be anti people. In real terms, politics in British India as well as in Pakistan has been one of antagonism between the class that ruled and the one that wanted to have the right to rule, and it would not be wide of the mark to call it a class war between the privileged and the privilege-seeking. Till the partition of 1947 it was the British bureaucracy that ruled, to be replaced by the Pakistani civil military bureaucratic conglomerate; and in both cases the patriotic nationalist movement sought to drive them away- one after the other. The enemy was obliged to leave. The most important difference between those who left and those who took over lay in the foreignness of the former in relation to the latter. It was racial, and not ideological. Because, so for as the politico-economic dispensation was concerned, the deporting and the incumbent rulers were committed to the some ideology, which could broadly be called capitalism. The old and the new were identical in their fear for, and hatred of a social revolution. And it was the dream of a social revolution that was at the centre of the liberation war of 1971. That revolution could have brought about a cultural revolution as well. We could have expected the secular and democratic values in our culture to develop themselves and, consequently, democratize the state. The class and communal divisions would have diminished. Bu the dream has not materialized. True, the communal division is not as potent now as it was before 1947, but the class division has widened and deepened. What seems to have been released by our victory in the liberation war is not the spirit of social revolution but of its enemy, the contrary force of capitalism. The capitalist economy and its values are bent upon driving away the democratic elements from both society and culture. Inequality has risen as never before, and patriotism declined almost in the inverse ratio. The presence and operation of capitalist values has become so overwhelming that the collective dream of socio-cultural liberation has been pushed into the background and profit-making, alienation and exploitation of the powerless by the powerful has taken on a pitiless character.

Culture constitutes identity. In the Pre-partition days, particularly in the nineteen forties of the last century, the Hindus and the Muslims of Bengal had tried to forget their Bengali cultural identity and to unfurl their communal identity as a matter of pride, and build up a defence mechanism for themselves inside religion. The consequence, we recall has been nothing short of a disaster. But since 1948 we in East Bengal had turned to Bengali nationalism, discarding the religion-based two-nation theory. This nationalism had in it the potentiality of bringing down class and communal divisions and of creating a unified Bengali culture with democratic substance inside it. But this was not be; primarily because of the political leaders who had pinned their hope of material prosperity on the promotion of a very crude form of capitalism. Class division has become furious in its advancement, and the rich and the poor stand as apart as not be able to communicate with each other, culturally. The ruling class makes use of religion as an effective and tested device of diverting people's attention from the secular world of poverty, injustice and tears; and the well-to do in society engage themselves with gusto in setting up madrashas and religious institutions with the undeclared motives of keeping the poor poor and of making easy material investment for otherworldly happiness. Both motives are connected with capitalist culture. After liberation the Bengali cultural identity had become a matter of pride not only for those living in Bangladesh but for Bengalis everywhere. But with the rise in corruption, alienation and exposure to the threats of climate change that pride has sharply declined. Capitalism has triumphed and Bengalis no longer enjoy the prestige they had acquired immediately after liberation. Having won a war we have managed to lose the honour we had gained. But one cannot do without an identity and in some quarter the former Muslim identity has come back as a replacement. To be known as a Muslim make them feel different from the Christians and whiles who have all the material power. The Muslim identity allows them, they think, the privilege of being part of a large international community. The challenges before the new state in Bangladesh were many, and all of them were related, in one way or another, to the development of a democratic culture. To achieve that goal it was essential that the Bengali language should be put into use at all fields of life and levels of activity, including bureaucracy, judiciary and education. Had we been successful there we would have become creative and natural, moving ahead and winning honour. The use of Bengali would have brought us closer and made it possible for us to be under a democratic system of social and political governance. Minimisation of class division would have made us culturally united, which unity would have made us a nation in the proper sense of the term. That we have failed to put the Pakistani war criminals and their local collaborators on trial has had a deep psycho-cultural impact. For one thing, it showed that the worst among the criminals can get away with impunity; for another it displayed an indifference toward establishing justice and vindicating national honour. That the rate of criminal offence has been continually going up and crime is being looked upon not as violation of human rights but as an accident is not unconnected with our tolerating of the genocide perpetrated by the was criminals. In the ultimate analysis, capitalism is anti culture. It makes people unsocial and encourages them to be self contred. Whereas culture believes in brining people together, in a relationship of mutual cooperation and understanding capitalism promotes exploitation of many by a few. Within the subjugation of capitalism trade flourishes at the cost of creativity. Men and women become consumer of commodities, which is supposed to be a sign of modernity. Education, health-care and even justice have become commodities, which have to be purchased and those who fail suffer. Culture itself has to look for a market. It is certainly not without significance that in Bangladesh today cultural programmes have become difficult to organise without the support of a commercial sponsor. To be fashionable one has to speak in either vulgar or pidgin Bengali, and the use of Bengali correctly sounds artificial and pretentious. The way political leaders, who are supposed to be role models, abuse those who oppose them would have been considered unimaginable before liberation. And of course in their anger they speak in Bengali. Women suffer. There is no denying that women's participation in all walks of life has increased, phenomenally. They are no longer under domestic confinement as in the past. But violence has entered domestic life itself, with women becoming victims. Sexual harassment continues unabated--not only in work places but also on the streets. Even teachers are found to be guilty of sexual misconduct. The so-called purdah was not unknown in the country. But never before had we seen young and smart women in such a large number moving about wearing burkhas as we do in these days of emancipation. Women cover themselves up to make their presence as inconspicuous as possible and also, at the same time, to declare their unconditional surrender to male hegemony. Bureaucracy remains; it has become an inseparable part of our culture. Bureaucracy is formal, artificial and not particularly human. Human relationship in Bangladesh tends to be bureaucratic, which is in no way helpful for the advancement of a democratic culture. Thus what is happening to culture is, to a large extent, attributable to political invasion. The state continues to be bureaucratic, and the material basis that culture needs is unapologetically capitalist. The state favours capitalist development and the rulers are firm believers in capitalist ideology. The pressure of population growth and unemployment are creating a new-anarchic situation in Bangladesh. To this politics seems to be indifferent, democratic culture hates anarchy, but the political culture of Bangladesh does not. Politics, therefore, has to be changed. For that what we need is an alternative political movement. And that movement has to be both patriotic and democratic. It would reject the current trend of politics and seek to build up a democratic state and society. The onus is on those who feel that a change is necessary. They must come forward. The collective dream of emancipation has to be revived and be made, once again, as it was in 1971, the basis of unity among the people. The political movement will need cultural components. Cultural activities are essential, and they should be ideologically oriented. The ideology has to be democratic and anti-capitalist. To begin with, we must put the Bengali language where it belongs, namely at the heart of nationalism and culture. Bengali has to be made the medium of education, communication and administration. It needs enrichment for which no effort should be spared. A deep and abiding attachment to the language would take us beyond class and help us to be secular in outlook. We have to cultivate rootedness in our culture to be truly international; and that internationalism would be based not on globalisation but on solidarity in a common struggle to improve the world in all respects. Capitalist politics must not be allowed to infringe on the rights of culture to follow freely and without pollution. The writer is Professor Emeritus, Department of English, University of Dhaka.

|

||||||||||||