Photo: AFP

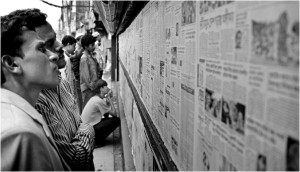

State of the fourth estate

Shahid Alam

We begin with a cliché, however familiar and jaded it may have become, because it is as near a cardinal principle of a liberal democratic state as the other similar attributes: universal suffrage, periodic election, competition for office, and the rule of law. Primarily for acting as a watchdog over any inclination to take recourse to excess of democracy that its innate liberalism opens the door to freedom of speech and the press has to be an integral part of a democratic state. The importance of the press did not escape the notice of British parliamentarian Edmund Burke, who is considered to be the philosophical founder of modern conservatism as much as he is regarded as a staunch representative of classical liberalism. He, as far back as in 1787, had recognized the importance and power of the press by anointing it as the Fourth Estate.

As 2010 drew to a close, what does the Fourth Estate in Bangladesh look like? By no means is it in the most robust health, although it is far from being in a sorry state. The print media is vibrant all right, although not always adhering to exemplary quality or lofty ethical standards, a phenomenon that has not infrequently placed it at loggerheads with political elements of various shades and status over the last several years, with the situation progressively getting worse with each passing year. Article 39 of the Constitution guarantees freedom of the press, but its application has fallen short of the ideal, crucially, both before, and since, the emergency interregnum. It comes as little surprise, then, that Bangladesh was ranked 138 (jointly with Liberia) out of 195 countries in a listing of global press freedom rankings for 2009, and, critically, was tagged with the status of its press as being 'not free'.

Going by what has transpired in the media arena since the 2009 report was published, it does not appear that this country will shed that tag when the 2010 assessment is made public, although, on the plus side, new daily newspapers have made their appearance on the national scene.

To go back to the topic of the state of media freedom in light of reports of annual increase in the number of media professionals being subjected to various forms of repression, harassment, and physical harm since 2007.

|

Photo: AFP |

According to the Bangladesh Journalism Review (BJR, Vol. 5, Issue 11, March 2009, p. 32), in 2008, 166 media professionals were subjected to various forms of repression, harassment, and physical harm. The state of affairs prior to 2008, as documented by the Bangladesh Manobadhikar Sangbadik Forum (BMSF), a human rights journalists association, was by no means satisfactory in the context of journalistic freedom. BMSF records that, in the 2006-07 period, political leaders and political party activists verbally abused journalists on various occasions. It documents at least 89 incidents of violence that were perpetrated by the BNP-led alliance in 2006. Significantly, plenty of media bashing and harassment of journalists took place when the press unearthed, and reported on, corruption and anomalies purportedly engaged in by government ministers, Members of Parliament (MP), local leaders and BNP activists.

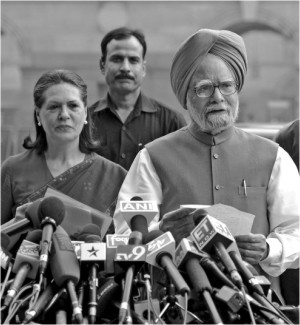

Soon after the proclamation of emergency on 17 April 2007, the military-backed caretaker administration issued a letter to all the country's media outlets, asking them to refrain from publishing or broadcasting ill-motivated, hurtful, or misleading reports about anybody. The expansive term “anybody” could serve as enough of a pretext to be used for curtailing press freedom. It could be expected that, during an emergency situation, normal activities could, and often would, function abnormally, but, based on the evidences of adversarial attitude of politicians of all stripes towards journalists the scenario has not changed for the better following the assumption of power by the AL-led grand alliance in 2009.

For a non-Bangladeshi perspective on the state of media freedom in Bangladesh, Vincent Brossel of Reporters without Borders, in an article written on 20 June 2010, presented a rather grim scenario obtaining in the country in the first half of 2010, while alluding to a similar situation that had existed before: “The recent developments in Bangladesh are like an old nightmare that is beginning again: arbitrary arrests, closure of news media, attacks on journalists by ruling party supporters, torture of detainees and intimidation.”

|

Photo: AFP |

The 2008 figures quoted earlier serve as the starting point of our post-2008 discussion. To underscore the position that repression, harassment, and physical violence committed against the media professionals increased since then, some actual figures are presented that could form the basis of extrapolation. In the first two months of 2009, 35 journalists fell victims to similar high handed acts (BJR, March 2009, p. 15).

Odhikar, another human rights organization in Bangladesh, in a report for January-March 2010, came up with the number of 97 instances of violence that is tantamount to creating obstacles to freedom of the press, while ASK has came up with the figure of 74 instances of journalist harassment during the period from April to June 2010. Although the variables used by the two organizations to arrive at their respective figures are slightly different from each other, their sum total would come to 171 for the first half of 2010.

This trend is disturbing, especially as the confrontational situation between the media professionals and the politicians seems to be taking a turn for the worse with each passing day. This is a state of affairs that requires rectification, for democracy to function better.

Following the Information Minister's announcement in July that the government was contemplating the introduction of legal measures to target yellow journalism, we were treated to a diatribe by the country's legislators against the press for real and perceived wrongs committed against them by that institution, to be followed soon after by a verbal salvo against a prominent news daily and its editor by the prime minister's health and social welfare advisor for supposedly indulging in yellow journalism. This just will not do, if liberal democracy in its true spirit, where two of its bastions work without considering each other as inveterate enemies, is to function vigorously in this country.

|

Photo: George Marks |

In Bangladesh, notwithstanding the vendetta at times waged by politicians in power against real or perceived opposition media professionals and establishments, we have seen examples that are a microcosm of a growing trend in yellow journalism over the years, worryingly during the stretch of parliamentary democracy that had begun in 1991. The present grand alliance government is evidently worried enough about the phenomenon for its Information Minister Abul Kalam Azad to announce plans to introduce new law to target yellow journalism because “newspapers and television and radio channels that are making false and misleading news to tarnish the image of ministers, lawmakers, the government and the country are in fact doing yellow journalism.” Similar complaints were heard during the previous three democratic administrations. Although Azad mulled over introducing a new law against "yellow journalism" he has not raised the issue any more in the face of sharp reaction from the jounalist community.

In Bangladesh, one would find instances of journalists quite regularly reporting negatively on the government, big business, institutions, legislators, and even the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition in Parliament (who was the previous head of government). Such criticism of the head of government, although intermittent and often sharp occurs in spite of the provision of Section 99A of the Code of Criminal Procedure that stipulates imprisonment in case of defamation.

The instances of highly critical reporting and commentary related to the government, et al, are almost exclusively restricted to the print media; the broadcast media is conspicuously docile, preferring to chart safe waters that will not ruffle too many important political feathers, or to be generally supportive of government policies and programs. The state-controlled television and radio channels, Bangladesh Television (BTV) and Bangladesh Betar, respectively, like many other similar government-controlled institutions in other countries, only toe the government line, with little news of opposition political parties and their leaders, and even fewer that is positive. In this context, it might be noted that (as well as being instructive on the nature of democratic practice and mindset in this country), for all the sanctimonious pronouncements of the major political parties prior to national elections professing to grant full operational autonomy to the state-owned media institutions, they invariably fail to do so on assumption of the reins of government.

|

Photo: Thinkstock Images |

The realistic scenario is that the print media professional has been known to pursue his/her own brand of critical journalism, which may, on the face of it, indicate the existence of a free and vibrant press, but, on closer inspection that requires an entirely separate study, will reveal several qualifications that will present a more circumspect picture. Keeping this whole context in perspective, it is precisely what passes for reporting on seemingly everything and everyone without fear that often lands Bangladesh's journalists in trouble, placing them at loggerheads with mostly politicians, who have both clout and muscle power, and use them as retaliatory measures, as well as with ordinary citizens, who do not possess such power, and usually vent their anger and frustration to anyone willing to listen to them.

2010 saw several strident criticisms of the media coming from the direction of important political figures, including inside Parliament. The state of affairs got to the point where the prime minister got irked about the disparaging comments made by a couple of her ministers and a few lawmakers in the legislature. Largely because of the nature of politics and that of the media, a degree of friction may be expected between politicians and media professionals in any society, except the totalitarian systems. This is not necessarily an unhealthy state of things; on the contrary, it can contribute to a healthy, vibrant democratic system by a responsible watchdog media keeping errant politicians in check from unwarranted and uncalled-for transgressions from their functional parameters. They key word is “responsible”.

I will take a holistic view of this unsatisfactory state of affairs existing as 2010 was drawing to a close, and state that this unhealthy situation is a reflection of a general lack in sections of both the groups of a key ingredient of liberal democracy: a mindset for its essential elements, and which has become a part of each person's persona. That incorporation will, crucially for the two groups (but probably applicable more to the political elements), take in tolerance of other opinions, however repugnant to one's own, and responsibility.

|

Photo: AFP |

This last attribute should lie at the very heart of first-rate, objective (not necessarily impartial) journalism, something that is absolutely essential for the spirit and practice of liberal democracy. Bangladesh needs to permanently establish the ideals of liberal democracy in its letter and spirit.

The media, howevert, cannot think itself to be omnipotent, and still proclaim itself to be a catalyst of a liberal democratic system functioning in the country. The politician, because of the inherent attribute of leadership that comes with his/her vocation, will have to lead by example in developing the mindset for the democratic spirit within him or herself. The media professionals will have to do the same in order to be able to spread the democratic spirit through their writings and commentaries. The Fourth estate is too important an institution to come under negative scrutiny through being treated in a cavalier fashion by the politicians and a section of its professionals.

The author is Head, Media and Communication Department, Independent University, Bangladesh.