|

|||||||||

Editor's note Turning Forty In absence of decent middle cinema Searching for remains of a Martyr Constitutional rights versus reality Of Carnage and Krishnachuras When history took shape and substance The Unfinished Revolution: Women’s Empowerment Starting at home Mainstreaming Resistance? Bangladeshi Writing in English Is Patriotism Alive and Kicking?

|

|||||||||

Dhaka Friday December 16, 2011 |

|||||||||

Bangladeshi Writing in English Fakrul Alam

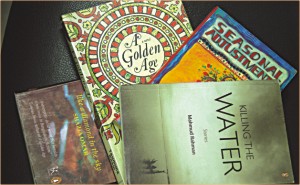

Why do we have so little Bangladeshi writing in English? And why aren't Bangladeshis taking to writing creatively in English in ever-increasing numbers as is the case with Indians, Pakistanis, Sri Lankans and, nowadays, even the Nepalese? Looked at qualitatively or even quantitatively, there isn't much to talk about as far as the literary pieces that have been written in English over the years by people from our country are concerned. In contrast, it is easy to see that not a few Indian writers took to the language with considerable enthusiasm soon after partition. One can of course argue that writers like R. K. Narayan and Mulk Raj Anand simply continued to write on in English after independence. What is clear, however, is that by the 1950s poets like Nissim Ezekiel emerged who simply opted to write in the language despite the provision of the Indian constitution adopted after partition that stipulated that English would be used for official purposes for only fifteen more years. What is notable, also, is that every decade in post-partition India has seen the emergence of new and distinctive English language authors. Salman Rushdie's masterpiece Midnight's Children (1981) simply confirmed not only the global presence of Indian writing in English but also the impact of diasporic Indian authors who have become celebrities in international literary circuits. The success of Rushdie's novel also apparently galvanized others and now there are quite a few writers joyfully offering their unique takes on life through it and in a few cases, even chutnefying it. Similarly, Pakistanis could take pride in the works of Taufiq Rafat, Zulfiker Ghose and Bapsi Sidhwa and Sri Lankans boast about the Booker prize winning Michael Ondatjee or the impressive Romesh Gunesekera well before the twentieth century ended. Noticeably, too, Indian Bengali writers such as Bharati Mukherjee and Amitav Ghosh to name only two, have made their presence felt in British and American writing by the end of that twentieth century. What is more, writers with Bengali links think of Arundhati Roy, Vikram Seth, Anita Desai and Jhumpa Lahiri -- had carved distinctive spaces for themselves in contemporary letters by the turn of the millennium. Noticeably, at least a few Indian writers were producing quality work in English as well as their mother tongues (Arun Kolatkar or Kamala Das are examples). Why was there, then, so little Bangladeshi writing in English in any form all this while and where were the diasporic Bangladeshis as far as English writing was concerned? It was not that the part of India that became Bangladesh in 1971 totally lacked people with the ability to produce quality English prose or verse. After all, Fuzlul Huq's rhetorical skills in the English language is on display in Bengal Today (1944), an impressive book based on his letters to the Governor of Bengal in which he articulates his protests against the British ruler eloquently. Buddhadev Bose, as we all know, had opted to write in Bengali even as a youth but his An Acre of Green Grass (1948) demonstrates that a writer educated in East Bengal could write lucidly and elegantly in English if he wanted to. And then there is the case of that splendid autodidact Nirad Chaudhuri who wrote wonderfully provocative English prose that seemed to have been originally stimulated by remote Kishoreganj! And yet the sad fact is that there has been very little Bangladeshi writing in English worth mulling over. Kaiser Huq has written enthusiastically about Syed Walliullah's Tree Without Roots, published in 1967 by Chatto and Windus in London as “the first novel in English by a Bangladeshi writer” (see his review of the Bangladeshi edition reprinted in The Daily Star Book of Bangladeshi Writing, but the book is essentially a “transcreation” of the Bengali version and has had no influence at all on subsequent Bangladeshi writing in English. Feroz Ahmed ud Din published a slim collection of poems called This Handful of Dust in 1974 that could undoubtedly be called promising at that time, but the work came out from Kolkata as a Writers Workshop book and very few people, I am sure, have any recollections of it now. Similarly, Razia Khan Amin's volumes of verse, Argus Under Anesthesia (1976) and Cruel April (1977) have real merit, but these books have left very little traces on anyone who aspired to write in English afterward. Mention may also be made of Niaz Zaman's short fiction, written over the years and collected in a few books, and Rumana Siddique's collection of poems, Five Faces of Eve: Poems (2007), but once again they have not led to anything much anywhere. Indeed, Kaiser Haq is the only English language poet from Bangladesh who has had any kind of presence not only in the country but also in the wider world and only he can be called a major voice as far as Bangladeshis writing in English from within Bangladesh are concerned. He has been a source of inspiration not only because he has published quality verse steadily over three decades now but also in the way he has kept evolving as a poet. Definitely, he has found his métier as a Bangladeshi poet writing in English. That his poetry has been anthologised overseas and he has been written about by others also make him stand out among those who have written in English while staying in the country. One could argue, however, that Bangladeshi writing in English hasn't done badly if we consider the writers of the Bangladeshi diaspora. After all, Adib Khan's Seasonal Adjustments won the Commonwealth Writer's Prize for the Best First Book in 1995 and his subsequent novels have attracted many reviews in Australia and elsewhere. Monica Ali's Brick Lane has been acclaimed by critics in both England and America and was even short-listed for the Booker Prize in 2004. Tahmima Anam's A Golden Age (2007) also attracted considerable attention on publication. This is no doubt an impressive list but these writers haven't had any impact on Bangladeshis aspiring to write in English. Also, they have not had the kind of influence Rushdie or Amitav Ghosh or Jhumpa Lahiri or even Michael Ondatjee have had. Noticeably, these writers have been feted globally but have also made their presence felt among their people. All the three Bangladeshi novelists mentioned above have followed up the success of their debut novels with works that have attracted some attention in the countries in which they reside in but except for Anam's The Good Muslim, which has just come out in a Bangladeshi edition, who in Bangladesh has had access to what they have published afterward? No, the conclusion is inevitable; there is very little Bangladeshi writing in English of value and not much to be excited about the work that has come out of our country or outside it in the language. Why hasn't Bangladeshi writing in English taken off? One can only come up with a few quick answers here. Linguistic nationalism, the raison d' etre of the country, had cornered English for far too long and though English has steadily made a comeback in schools, colleges and universities since the 1990s, it will take a long time to put the English language in good kilter again or at least bring it to the point at which people feel tempted to imagine the world through it. Indeed, it is not difficult to see from here that the complacency that we are a homogenous nation has cramped most of us in many ways. For far too long cultural nationalists have had a kind of superiority complex that led them to declare that there was no scope for writing creatively in any other languages in this country. As for the Bangladeshi diaspora, no doubt the first wave of emigrants has for too long been preoccupied with consolidating their presence in the countries that they had landed in. Most of them did not have the kind of education that would have encouraged them to write creatively. In all probability, they did not use English at home. Nor did they ensure that their children were not sequestered from the English language once they came inside the house. How, then, could their children grow up into adults who could write creatively about the “aloofness of expatriation” or the “exuberance of immigration” in English verse or fiction? (Bharati Mukherjee's words)? And the few that had the kind of education necessary to articulate their consciousness in English appeared to have opted to be doctors or engineers or bankers instead of daring to be writers afloat in a world where financial security was not the chief reason for living abroad. Also, very few of the new generation of educated Bangladeshis who were growing up abroad had decided to shuttle back and forth between the land they or their parents had left behind and the countries they had become citizens of, as did Rushdie (before the fatwa), Mukherjee, Ghosh or Lahiri. These writers had embraced a kind of mobility that allowed them to write about emigrant lives or return to lands left behind. Finally, until recently, very few of the Bangladeshis who had been educated abroad where they had begun their careers wanted to come back home to start businesses or begin careers and write creatively on the side. But is this situation going to change and will we be able to see Bangladeshi writing take off soon? The signs, lately, have been on the positive side. There are more and more poets and writers of fiction and verse following the paths pioneered by Razia Khan Amin, Kaiser Huq and Niaz Zaman. The publishing house writers.ink has now lasted for close to a decade even though it has decided mostly to showcase people writing creatively in English. The performance group Brine Pickles has been encouraging young writers to do experimental work in the language for a few years now. Last month the mostly Bangladeshi writers' collective based in Dhaka called Writers Block brought out a lively anthology called What the Ink? Surely the best word to describe the recently concluded Hay Festival in Dhaka is “vibrant”! Tahmima Anam has been coming back to Bangladesh again and again and is clearly bent on publishing a worthwhile trilogy rooted in the land she left behind as a child. Judging by her contributions to The Daily Star weekly magazine Sharbari Ahmed appears to be on the verge of publishing something noteworthy in English writing sometime soon. One must then continue to hope and look for the breakthrough work. Will Bangladeshi writing in English take off in an exciting way in the not too distant future? The answer has to be “yes”. Here is wishing that it will have the verve that has characterized works of Indians, Pakistani and Sri Lankan authors writing in English for some time now. Surely its time is coming! The writer is Professor, Department of English, Dhaka University. |

|||||||||

© thedailystar.net, 2011. All Rights Reserved