Looking back and ahead

Serajul Islam Choudhury

With hindsight our political history looks both spectacular and curious. Valiantly we have fought for independence, liberation, emancipation and the like, but we have also allowed ourselves to be led into despicable quagmires. One of the worst disasters in our history has been the partition of 1947. To the understanding of many it stands next only to the Battle of Palassey. The consequences of the partition of the subcontinent, particularly that of Bengal, continue to be felt by us even now.

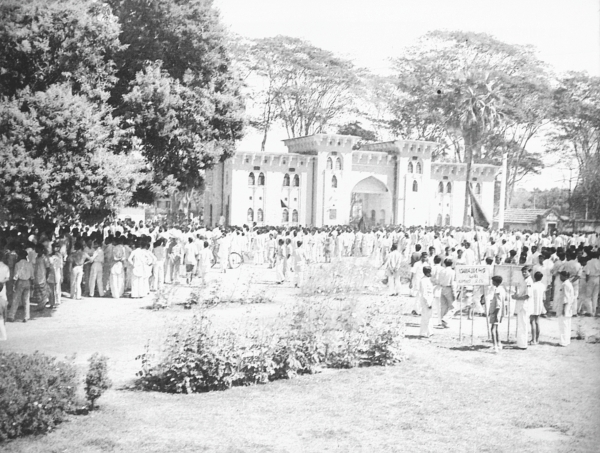

Archive

Archive

But we have not surrendered. The protest against the tragedy of 1947 began almost as soon as it had happened. The people's uprising in 1952 was manifestly in demand of Bengali as one of the state languages of Pakistan, but its significance lay much deeper. Indeed, it was the first spontaneous public revolt against the newly set-up state itself and signified not only resistance to the design of foisting Urdu as the state language of Pakistan on the people of Bengal but also, and more importantly, rejection of the unnatural two-nation theory which formed the very foundation of the state. The goal was not clearly pronounced at the beginning, but it was there inside the movement itself. It would be said that we were demanding provincial autonomy, and perhaps, as some did suggest, the urge was for the implementation of the Lahore resolution demanding not one but two separate states within a federal union. But the rejection of the two-nation theory and the turning to Bengali nationalism had within itself a clear-cut objective declaration which was that Bengali had no reason to be one of the two state languages but every reason to be the only language of the state.

Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who was known for his clarity of vision, was peculiarly unclear about the implications of the nationalism of which he had become the only spokesman. He wanted India to be divided, but declared that he would fight by the inch against the partitioning of Bengal and the Punjab. He was not prepared to admit that the very argument he was putting forward for the division of India supported a 'surgical operation' of the two Muslim majority provinces that the Congress leadership demanded. One of Jinnah's declarations at that historic moment is memorable. Finding that the partition of the two provinces was inevitable, he wrote to the Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, on 17 May 1447: "The partition of Bengal and the Punjab cannot be justified -- historically, economically, geographically, politically or morally". Of course, he was right. But what he said on that occasion was precisely the argument the Congress leaders were putting up against what they called the vivisection of India.

There is no reason to doubt that Jinnah knew that the people of Bengal and the Punjab were united because of their language and that the Bengalis and the Punjabis considered themselves to be separate nations as did the other linguistic communities in India. He was not unaware that the people of the two important provinces knew themselves to be Bengalis and Punjabis first and Muslims afterwards, but he was unable to accept that to be true, because to do so would mean the destruction of the very basis of his claim for Pakistan. He was opposed to the partitioning of Bengal and the Punjab because he expected the two provinces to be part of Pakistan in their entirety.

And yet he was obliged to admit, as soon as Pakistan came into existence, that a state based on the two-nation theory was not viable. He had seen for himself the misery in terms of loss of life and property together with the exodus of the minorities from both sides of the artificially created border. He is known to have shed tears privately at least on one occasion at the sight of the sufferings of the refugees at a camp in Karachi. Jinnah did not, of course, live to see the subsequent disasters, the ugliest of which was created by his favorite Punjabi army in 1971 in East Bengal. He had realised that religion could not be the basis of Pakistani nationalism for the simple reason that there were a large number of non-Muslims within his state who could not be driven out, nor could the Muslims he had left behind in the Indian Union be brought in and accommodated in Pakistan. He had to find a new bond to unite his citizens and thought, very wrongly, that Urdu would serve the purpose.

The dream of giving the Muslims of India a happy homeland having turned into a nightmare, Jinnah attempted to create a new dream of achieving unity through the imposition of Urdu as the state language of the new state. In reality, a more undemocratic course of action would have been difficult to conceive, for 56 percent of the population of the state were Bengali-speaking and Urdu was not the mother tongue of even five percent of the West Pakistanis. The move would certainly have created another nightmare had the Pakistani rulers decided to stick to their guns.

Well, we have fought and driven the Pakistani rulers away. The price has been heavy, but the achievement is great. The most evident signpost to our gain is that for the first time in our history Bengali has become the state language. Underneath that glory there was the expectation that the entire nation would be emancipated from economic hardship and misery, and that we would now have our honour established in the international world, and that, in a word, there would be a total improvement in the quality of life itself. Needless to say that the expectation has not been fulfilled. To be precise, we hoped that there would be a social revolution in independent and sovereign Bangladesh, which social revelation had been made impossible by the colonial rule of the British, and later, by the semi-colonial repression of the Pakistanis. What has happened over the years is that the gap between the rich and the poor has widened; chaos and even anarchy have become visible in all walks of life and society. The Bengali language itself, the advancement of which we think should be the signpost to our progress, has been denied the place it should have been given in the interest of our own prosperity.

Bengali has not become the medium of education at all levels. Its place at the level of higher education is not at all honourable. The three systems of education are widening the class division instead of uniting society, as education should do. Bengali has not become the language of the higher judiciary.

Every language has a standard of its expression, usage and pronunciation established through the efforts and contributions of writers, speakers and users of the language. Bengali has also its own standard, and it is this standard which has been subjected to continual attack not by the illiterates but by the rich and educated classes. Very often their speeches are a hodgepodge of English words, phrases and expressions mixed up with rural, local and vulgar terms and words. They use it with reckless abandon, basking in the sunshine of the freedom acquired for them by the millions who had fought for their own emancipation.

The electronic media and FM radios think they are doing their audience a favour, but what they deliver through their advertisements and presentation is nothing short of an organised assault on standard, normal Bengali. The young are being given by them an idea of smartness which consists in wrecking the standard. Through the hospitality offered to the Indian TV channels the Hindi language manages to enter our quarters, including the bedrooms, causing irreparable harm, particularly to children. We had resisted the encroachment of Urdu, which it has to be admitted is a richer language than Hindi, but we have opened our doors and windows to this new guest, who is in no way a friend of ours.

The literacy rate has gone up, but literacy is no indicator of education. The semi-educated do not know the use of proper Bengali, the educated do not care for it. In the educational institutions linguistic errors -- written as well as spoken -- are not corrected by teachers, who themselves remain indifferent to the need for promoting standard Bengali.

The language situation can never be separated from the state of the nation as a whole. That we should rank among the most corrupt nations in the world, that our share market should be called the worst in the world, that our streets should be the most dangerous the world has known, that we should be the most vulnerable country to climate change, that our international border should be among the bloodiest in the modern world, that we should allow our scarce mineral resources to be taken away by foreign companies and that we should fail to map the area of the Bay of Bengal that belongs to us need not surprise us. What is necessary, however, is to note that all these are of a piece with the sufferings that our mother tongue has been putting up with in this sovereign land of ours. There is no denying that what the face is to an individual, language is to a nation.

But a nation's language is more than a mirror, for it is as much part of the superstructure as of the basic structure of a society. It is a means of communication, and is even more important than the mechanical methods of contact. It connects the present with the past and looks forward to the future. Language stores and makes available the knowledge and wisdom that generations of great men and women have created both at home and abroad. As a medium of education its value is incalculable. Education can never be natural, deep enduring and universal unless and until it is given through the mother tongue. Creativity itself suffers when the mother tongue is denied opportunities to forge ahead. It unites a people and gives it a sense of collective identity and honour that nothing else has the capacity to do. Today Bengalis are a large group of people, comprising 26 to 27 crores in number but they do not also enjoy the pride of place they should have because of their failure to cultivate and enrich their mother tongue. We have not been as serviceable to our language as we ought to have been. The liberation of Bangladesh offered us an opportunity as never before; but we have failed to make use of it, and have remained as marginalised as we have been in the past, although personally many of our men and women have established themselves in different fields of activity, bringing honour to their own selves as well as to all of us.

But who is to blame for our collective failure? Not the people, but the class that rules the country. Bengali is a provincial language as far as West Bengal is concerned. The hope lies in Bangladesh. But that hope has been betrayed by our rulers. In the past state power has never been an enthusiastic promoter of the Bengali language. The British were indifferent, the Pakistanis hostile. But in independent Bangladesh we have a ruling class whose patriotism is on the decline. This is manifest in many areas, including their attitude to the Bengali language. It is only natural that their children should go to English medium schools and they themselves should travel abroad on all possible occasions. The affiliation of the ruling class, which comprises politicians, business persons and professionals, is to the capitalist world and they consider their knowledge of English to be an asset. Some of them do not think that Bangladesh has a future and that feeling inclines them to send their children abroad, transfer money and even buy accommodation outside the country.

Language unites, but it can also separate. It is typical of rulers everywhere that they would use a language suitable to indicate their distance from those whom they rule. Those of our rulers who came from outside had the advantage of having their own language. Our local occupiers do not have that privilege. In their deprivation they have forged their own lingo. Political leaders are expected to act as role models to the public. The models the leaders in Bangladesh hold up have nothing to make them feel proud. And yet because they are known, visible and powerful they have their impact on the public. As far as the use of language is concerned, their influence is in no way less harmful than the examples of their activities in other fields of life. Parliamentary debates enrich a language; they contribute to the creation of a standard language. But the Bangladeshi politicians find themselves incapable of doing that. To hear them speak in the National Assembly as also in public meetings is to be aware of how far away they are from the educated norm. The fact that the ruling class in Bangladesh is a hindrance to progress in all fields, including that of the Bengali language, can hardly be exaggerated.

What we need is people's democracy, for which we have been fighting for ages, and we must continue to do so without losing heart. Nightmares created by the rulers have been disrupting our collective dream. Those who are patriotic have to carry forward the struggle for the realization of the collective dream of emancipation, enrich our mother tongue and discard the idea that independence means a mere change of rulers. Meanwhile, it is important for us to realise that the enemy of the people's language and the enemy of the people are identical.

Professor Serajul Islam Choudhury is an academic, scholar and social critic