Time to light the lamps

Syed Badrul Ahsan

These are thoughts that well up from somewhere deep in my soul. They rise, they gather in the core of the heart in me, to remind me that there was once a time when pride and tradition came together to let me know that I was a Bengali. In July 1971, as my parents, my siblings and I prepared to leave what is today Pakistan and make our way to an occupied Bangladesh, my teachers and my friends told me in something of a polite whisper that they hoped conditions would return to normal in 'East Pakistan' and that we could remain brothers for all time. I was in my teens. I had heard of the atrocities Pakistan's army was carrying out in Bangladesh. I had, with something of macabre happiness, watched army trucks transport, along the road before my school, coffins carrying the bodies of Pakistan's soldiers killed by the Mukti Bahini in Bangladesh. My friends looked morose, naturally.

|

|

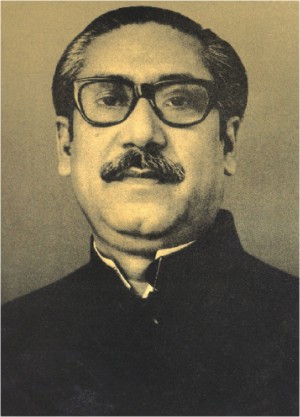

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman whose historic March 7 speech ignited nationalistic zeal in the hearts of Bangalees. Photo: Star Archive |

For me, those sombre vehicular movements by the army were intimations that Bangladesh would be a free nation someday. Like millions of other Bengalis, I had no idea when that day would dawn, but that Pakistan would someday become a bad memory best forgotten was a truth we held on to. And so, as the time drew near for my family to board the train to Karachi and then a long, circuitous Pakistan International Airlines flight to occupied Dhaka, I told my teachers and my friends that the next time I found myself in Pakistan it would be as a citizen of a free Bangladesh republic. They looked at me, aghast, as horrified as they had been on a day a couple of months earlier when I had refused to acknowledge Mohammad Ali Jinnah as the father of the nation. Predictably, a complaint made its way to the office of the school principal. I had not only rejected Jinnah but, challenged by a Punjabi classmate to demonstrate my courage, also ripped out Jinnah's photograph from my history textbook and flung it to the ground. The principal, a Dutch missionary, aware of my need for safety, simply wanted to know why I had committed such sacrilege. I told him I honoured my father of the nation. And it was not Jinnah. It was the imprisoned Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He looked at me for long seconds, before simply advising me, 'Be careful.'

It was on a cold, blustery January day close to a quarter of a century later that my English language and literature teacher, he who had advised me in the late 1960s to take up teaching or journalism as a profession (I have done both), recalled that moment a free Bangladesh beckoned me as I prepared to make my way out of (West) Pakistan. I was back in Quetta, no more a Pakistani but a happy, free and secular Bengali. For about a week I moved around that garrison town, walked along the old familiar streets, remembered that Colonel Taher too had walked those same streets post-March 1971 pondering his role in a gathering war of Bengali liberation. And I felt happy, meeting old friends, trekking down to the shops I had often visited with my father as he bought bread for the family every morning, feeling that certain sense of pride which comes of being part of a free nation. Back in school, for years I had led my platoon at the march past organised by the local authorities every time Pakistan's independence day was observed on 14 August. It was a story I recalled as I walked past the field where we had marched, saluting before a dais where a dignitary stood ready to enlighten us on the sacrifices that had been made in the struggle to achieve Pakistan. It snowed as I stood there, before that desolate field, wondering at the sacrifices my own fellow Bengalis had made in 1971 in their war to be free of a menacing Pakistan. Three million of my own people had died at the hands of the Pakistan state. Tens of thousands of Bengali women had been molested and raped by the Pakistan army, which had pillaged and burnt Bangladesh's villages for nine terrible months. It was these realities I remembered on that winter day. I felt no bitterness. I only tried understanding the mysterious ways in which history took shape at seminal points in the stories of nations. The universe was a strange place.

This morning, as we observe yet one more anniversary of Bangladesh's freedom, it is that secular spirit of Bengal I go back to. In 1971, as Pakistan's soldiers stopped Bengalis on Dhaka streets and peered inside their lungis to ascertain their religious affiliation, we wondered long and hard if we could ever free ourselves of that communal dispensation. And yet there were the men who instilled courage in us. The incarcerated Bangabandhu was, and remains, our hold on history. It was that season of darkness when the principles the Father of the Nation had left us with, before he was carted off to prison, lighted up the pitch dark before us. There was the Mujibnagar government, to let us know day after day that only freedom mattered, that out of the strife and all the debris around us we would reclaim our heritage and transform our geographically small land into an ideal democratic state. It was a dream that saw fulfillment on a December afternoon. Six days into liberation, as twilight descended on the country, the men who had given shape and substance to that government, the first in Bengali history, arrived home. Nineteen days after that homecoming, it was Bangabandhu's turn to come back to a land that had freed itself on the moral strength of his political leadership. For three and a half years thereafter, we lived in sheer enjoyment of liberty. We went hungry, we joined those long queues for rations, we went looking for the bones of those the Pakistanis and their local henchmen had murdered. And yet we looked upon that era as a stirring period in our history, for it spoke to us of the flavour in which freedom manifested itself in the lives of people who possessed the courage to dream.

These are the thoughts that course through me today. The thrill I lived through as a teenager is the thrill I would love to go through again in my fifties. But then come the thoughts, brooding if you will, which throw up images of the nightmares that supplanted our dreams only three and a half years into freedom. You and I can count on our fingers the numbers of all the brave men of freedom we lost in the years after liberation. Does a revolution invariably claim its heroes? Do counter-revolutionaries, lurking in the bushes, always push patriots aside and commandeer what would have been a society of enormously talented, decidedly dedicated men of patriotism? Reflect on the answers, if you can, to these questions. Dwell too on what all the good men calling themselves the Sector Commanders' Forum have lately been trying to do these past many years. Of course the elements of darkness who engaged in criminality in 1971, through dispatching our patriotic Bengalis to unnecessary and unfortunate death, should pay for their heinous acts. But should that job not have been done years ago, when Zia let these bad men in through his so-called multi-party democracy, when Ershad retrieved a collaborator and turned him into a minister?

These questions re-ignite the old pain in us. We have seen criminals murder the founding fathers of our free nation. Our war heroes, having waged long, twilight battles on the fields of 1971, died in internecine conflict in their liberated country. Our democracy, our socialism, our nationalism and our secularism were all done in by men we thought were the vanguard of our freedom back in 1971. Our soldiers have died on the gallows because a dictator had decreed thus. Yet another dictator sought to tamper with the judiciary and then put a communal cap on this Bengali state, to our undying shame.

It is time, then, to renew the old pledge. Despite this glaring absence of enlightened Bengali nationalistic leadership today, it remains for us to light little lamps in our homes and sing songs in our villages, to pass the message on that our struggle for emancipation goes on. The old dream refuses to die.

The writer is Executive Editor, The Daily Star.