Expanding

the Ekushey horizon

Muhammad

Zamir

........................................................

Despite

our glorious past, we are confronted today

with a crisis of confidence. Our identity

has become the source of debate. Intellectuals

of different persuasion argue endlessly

about aspects of our cultural ethos. This

inability to agree on a common identity

is casting its shadow not only on our socio-cultural

life but also on our approach towards politics

and international relations.

Although

we have an active cultural scene, the degree

of fluidity and the indeterminate nature

of our cultural background and its definition

have coalesced together to hamper a true

projection of our rich heritage.

Although

we have an active cultural scene, the degree

of fluidity and the indeterminate nature

of our cultural background and its definition

have coalesced together to hamper a true

projection of our rich heritage.

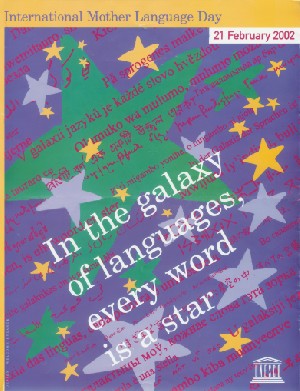

This

absence has assumed a significant dimension

given the fact that the sensitivity and

'chetona' of Ekushey have both received

international recognition. The national

language of Bangladesh and 21 February are

both today part of the world cultural inheritance.

The fact that UNESCO has declared 21 February

to be the International Mother Language

Day makes it incumbent upon us to be able

to project to the rest of the world an agreed

and basic culture that sets apart people

of Bangladesh from the rest of South and

South East Asia.

It

is time that we establish a matrix and try

to really agree on some fundamentals. We

cannot and should not continue debating

as to whether we are first Bengali and then

Muslim or the other way. Our exercise should

be to carefully examine the different elements

-- starting from the manner in which we

express our salutations to important factors

like language and literature, the philosophy

that encourages art, sculpture, music and

folk-lore. It is necessary to establish

a common ground.

Time

has now come for us to expand the horizon

of Ekushey. The facets that have contributed

so much to our national psyche need to be

projected abroad. We owe it to the rest

of the world in view of our international

responsibility. This has to be undertaken

carefully.

Our

Ministries of Foreign Affairs, Cultural

Affairs, Information and Science and Technology

should immediately set up a co-ordinating

committee to examine what steps need to

be initiated in this regard. A bi-partisan

approach will obviously help. If such a

policy can be implemented properly, it will

enhance our image and restore some degree

of credibility in the world stage.

The

Bangladeshi ethnic consciousness that has

inspired the gradual evolution of its culture

is based on a mosaic that includes the rural

background of its population. It is reflected

particularly in its pristine literary forms,

its poetry, its cuisine, its textile, its

music, its songs, its musical instruments

and choreography in dance forms. It is here

that we need to look for common links and

non-controversial elements in our nation's

cultural map. We can probably stress these

aspects at the time of the projection of

our culture. We need to work together without

politicising what we possess.

There

are musical expressions in Bangladesh where

there need not be any dispute. These include

rural poetic songs like <>Kabi gaan,

Jatra gaan and Baul gaan. These are extremely

popular forms of entertainment in the rural

areas of Bangladesh. They are particularly

liked because such art forms rely on inter-action

between more than one person. Consequently,

being practised in groups, they could form

the core for musical troupes going abroad.

These in turn could be constituted on the

basis of merit and not perceived political

affiliation.

We

need to also urgently consider whether there

can be expanded cultural cooperation with

our neighbours. We could possibly think

of entering into more intensive cultural

cooperation with other South Asian countries.

This can be done by organising cultural

festivals in these adjacent countries where

the cultural ethos of Ekushey can be highlighted.

Our own ethnic cultural diversity could

then be focused upon as is done by India,

Thailand and Indonesia.

The

next step should be directed at the western

group of countries, particularly those in

Europe, North America and Australia. Since

our independence, over the last three decades,

hundreds of thousands of people of Bangladeshi

origin have moved their residences to these

areas. In many cases they are full citizens

of countries in these regions, but they

retain their affection and linkage with

their motherland. It is important that we

evolve a national policy whereby we enter

into cultural framework agreements with

those countries where we have a fair representation

of Bengali speaking citizens.

In

today's electronic age, it should be possible

for Bangladesh to project its culture abroad.

It will require hard work and proper motivation.

This will enable us to expose the importance

of our language and our culture. If we are

to gain from UNESCO's decision and familiarise

the importance of Ekushey abroad, we have

to agree to work together.

Our

diplomatic missions will also have to shoulder

more responsibility in projecting more effectively

our traditions and ways of life. Each mission

should be asked to set aside a room where

regular classes could be held for teaching

Bangla not only to children of expatriate

Bangladeshis but also to children of the

host community if they so desire. Such a

measure would be similar to some of the

functions carried out abroad by the French

and German governments through their Alliance

Francaise and the Goethe Institut. People

abroad will then be able to associate themselves

with the importance of Bangla and Ekushey

as the International Mother Language Day.

Our

authors and artistes, be they involved in

music, poetry, novels, painting, sculpture

or cuisine must be made more easily recognisable.

This can be done through translations and

films which can be made available through

CDs and DVDs. These can be stored in libraries

in each of our Missions. Copies of important

Bangla publications in translation, traditional

Bangla music on CDs and posters with photographs

of our indigenous musical instruments could

also be distributed in important western

educational and cultural institutions.

Local

Bangladeshi Associations abroad should also

be encouraged to observe significant national

events jointly. The leaders and policymakers

of the host community could be invited to

these functions. Such an arrangement will

create greater respect for Bengali traditions,

folk-lore and rituals.

Bangladesh

stands marginalised today in the world cultural

scene. Yet, it is our language and the spirit

of Ekushey that have been chosen by UNESCO.

We are lagging behind because we are not

making full use of our potential. Gaining

wider respect and admiration for our literature,

art and music will require sincerity and

dedication. This can be done. We can start

with a careful examination of what we possess,

what we want to achieve and what we need

to do to get there.

There

is scope for us to benefit from international

cooperation in culture. The USA, European

Union, China, Korea and Japan and many other

countries, if approached, could become our

partners in this field. UNESCO has indirectly

opened the portal for us.

........................................................

Muhammad Zamir is a former Secretary

and Ambassador.

BANGLA IN PUBLIC OFFICES

Where

do we stand?

A

M M Shawkat Ali

........................................................

The

Proclamation of Independence and The Laws

Continuance Enforcement Order issued on

April 10, 1971 by the Government of Bangladesh

(then in exile) were in English. So was

the Provincial Constitution of Bangladesh

Order issued on January 11, 1972. However,

there is strong evidence that Ministers

started using Bangla in official files since

April 10, 1971. Foremost among them was

Tajuddin Ahmed holding the important portfolio

of finance besides being the Prime Minister.

A

civilian freedom fighter decorated with

Bir Uttom (BU) recalls how neatly and with

precision Tajuddin used to give his decisions

in Bangla in the official files. Once Tajuddin

turned down the request of a senior official

for return of a car which he claimed to

be his own. It was then in the custody of

Krishna Nagar police station in the district

of Nadia. The file was resubmitted for review

and decision to allot the transport. Tajuddin

gave his decision thus:

(Decisions

should not be changed frequently else one

would be guilty of deception. I don't want

to do it in this case also).

Bangla

was made the State language in the constitution

adopted in 1972. Most of the official notes

in the Secretariat as well as in the district

offices continued to be written in English

by the civil servants. The change could

not have come overnight. The first initiative

to break this trend was taken by no less

a person than the Prime Minister. This was

done as early as in February 1973.

On

February 1, 1973, the Prime Minister decided

that no files or other papers could be submitted

to him unless it was written in Bangla.

This decision was circulated to all Secretaries

to the government by the Prime Minister's

Secretariat. The other aspect of the decision

was that all forms and other documents of

the Ministries must also be translated and

printed in Bangla.

The

practical difficulties

The orders issued by the Prime Minister

did have its impact but difficulties were

being faced due to limited availability

of Bangla typewriters. More substantive

difficulty related to choice of words and

the style to be adopted i.e. whether it

should be in Chalti Bhasha (Spoken Bangla)

or Sadhu Bhasha (Polished Bangla). Both

the forms came to be used but the problems

associated with choice of words remained.

Initiative

by Bangla Academy

To overcome the problem of choice of words,

at the request of the government, Bangla

Academy took the initiative of bringing

out what it called Proshashonik PariBhasha

or Administrative Terms. This was published

on February 21, 1975. Some of the terms

suggested by the Academy proved difficult

and almost unintelligible. This is best

illustrated by a reallife story of a retired

Secretary who was, in 1974-75, Member (Administration)

in Bangladesh Water Development Board.

He

recalls that one day he got a call from

one of his senior colleagues who was a Director

in the Trading Corporation of Bangladesh

(TCB), later the Cabinet Secretary in 1996.

The Director asked his colleague to see

him immediately. As Member (Admin) entered

the room of the Director his eyes fell on

a small booklet titled Proshashonik PariBhasha

held in the latter's hand.

The

Director drew the attention of his colleague

to Bangla equivalent of the English term

civil service. The Bangla word was and still

is Jonpalok Kotrik. Both wondered if there

couldn't be an easier term such as shorkari

chakri or government service? At the other

end, the term 'Civil List' is shown to be

Bangla equivalent of rajpurshashuchi. Civil

List, the publication of which has been

discontinued since 1971, used to be a list

of civil servants with their places of posting

and the pay they drew. Why should it be

rajpurshashuchi and not jonopalonshuchi?

The

difficulties associated with finding appropriate

equivalents of administrative terms are

many and varied. Foremost among these difficulties

relates to the propensity to use high-sounding

Bangla words at times in a literal sense

without any reference to the context. Most

tend to be pedantic rather than practical.

The framers of Paribhasha probably are more

impelled by concerns to protect purity of

Bangla than by recognising the need for

adaptation of words, which are more easily

understood by common men and women. This

pedantic attitude still persists.

The

law to use Bangla

Our first Prime Minister, Bangabandhu Sheikh

Mujibur Rahman, who passed orders in February

1973 to the effect that all files to be

submitted for his orders must be in Bangla,

was pragmatic. He did not opt for making

it legally binding. He probably wanted to

initiate and sustain a process whereby Bangla

would be used in public offices. The military

leader-turned-politician after 1975 maintained

status quo and did not show undue haste

in the expanded use of Bangla. It is said

that he would sign in Bangla all files submitted

to him for orders. It would be simply “Zia”.

The

military-leader-turned politician who came

to govern the country in 1982 thought otherwise.

He enacted a law in February 1987 making

it compulsory to use Bangla in all public

offices. The preamble to the law reads that

it is desirable and expedient to use Bangla

in order to fully implement the provision

of article 3 of the Constitution. It further

lays down that a breach of the provision

would entail departmental proceedings under

the relevant disciplinary rules for misconduct.

The law also provides for framing of rules

to implement the objectives of the law.

There is a regressive feature in the law.

It requires that if any person makes any

application or appeal in language other

than Bangla to any public office, in that

case such an application or appeal will

be unlawful and without any effect. Imagine

a foreigner seeking a redress of his grievances.

He or she will have to go to a Muhuri (deed

writer) to have an application in Bangla.

How will he/she communicate with Muhuri

is another matter. At the other end, are

the international -- multilateral or bilateral

-- aid giving agencies. For them, an exception

has been made later by an executive fiat.

The public servants are permitted to use

English in such cases. The law has not,

however, been amended.

The

second round of the Bangla administrative

terms

Prior to the passing of the law in 1987,

the Ministry of Establishment took the initiative

to have a more improved version of Bangla

equivalents of administrative terms. The

objective, as stated in the memorandum issued

on the subject, was to achieve uniformity

in the use of terms in Bangla. A Secretaries

Committee and an Implementation Cell for

the use of Bangla were set up in March 1986.

Some improvement is visible but how far

it helps common citizens not familiar with

English is another matter.

For

instance, if the purpose is to communicate,

it is better to use commonly understood

terms rather than stick to Bangla words.

The oft-repeated anecdote relating to a

rickshaw puller who understood the term

university and did not at all understand

its Bangla equivalent (Bishwabidyaloy) is

a case in point. When the passenger asked

the rickshaw puller if he would go to the

“Bishwabidyaloy”, the latter

pulled a blank face until the English term

was used. No one in rural Bangladesh would

understand the term Bhaprapto Kormokorta

(officer-in-charge) when referred to in

relation to a police station. They would

be more than comfortable with the word OC.

Why then hang on to terms that are not understood

by the common man. It goes to the credit

of the British colonial administrators that

they did not find any English equivalent

of the term Chowkidar or Dafadar. These

two terms, thanks to the breadth of vision

of the colonial rulers, have been in use

for nearly two centuries.

It

is relevant to refer to the fact that the

Bangla equivalent of the word 'traffic'

as noted in the Poribhasha is ‘porijan’.

It is totally incomprehensible to the common

men and women. They happily use the English

term. Why then try to burden them with such

words? At the same time most drivers use

it in a different way. When a driver finds

it difficult to take a turn in the absence

of a traffic policeman, he uses the words

'Sir, there is no traffic here'. What he

means is that there is no traffic policeman

on duty. There is perhaps need for correction

here but certainly not in all cases.

Since

independence, lot of progress has been made

in the use of Bangla in public offices.

All official correspondence is in Bangla

except those meant for foreign agencies.

This need not blind us to the substantive

objective of achieving better and meaningful

communication with the citizens for whose

welfare administration is meant. The purpose

of better communication would be achieved

by adopting a less pedantic approach than

has been the case. The official use of Bangla

should approximate the language that they

understand.

At

the same time, we should also pay equal

attention to train our younger generation

of civil servants in English language so

that they do not feel shy to face foreigners

specially those involved in international

aid business. The Prime Minister in her

address at the Bangla Academy on February

7, 2004, has drawn attention to this issue.

In yesteryears also the Leader of the Opposition

in her capacity as Prime Minister spoke

in similar terms. Acquiring skill in more

than one language is a necessity from which

there is no escape. It need not be viewed

as neglect to Bangla. That indeed will be

a narrow view which is inconsistent with

the demands of time. Finally, we should

desist from showing our concern for Bangla

only in the month of February. The efforts

should be throughout the year to enrich

the language for the benefit of common citizens

and just not for so-called intellectuals.

........................................................

The writer is a retired secretary.