With

love for all languages

Muhammad

Habibur Rahman

.......................................................

mori Bangla bhasa!

What

a wonderful Bangla language!

Lovers

of mother tongues all over the world express

similar views.

A

natural bias plays an important part in

likes and dislikes of languages. No one

will say, "My language is backward

and inexpressive." We often tend to

regard other people's language as we regard

their culture with disdain, if not with

downright animosity.

There

is no reliable way of measuring the quality

or the efficiency of any language.

In

The English Language, Robert Burchfield

writes : "As a source of intellectual

power and entertainment the whole range

of prose writing in English is probably

unequalled anywhere else in the world."

It

is most likely that Mr. Burchfield would

not have made that assertion had he been

a born Russian or German or Chinese.

Chinese

writing possesses one great advantage over

other languages. It can be read everywhere.

People can read their literature of 2500

years as easily as yesterday's newspaper,

even though the spoken language has changed

beyond recognition. It is has been said

,"If Confucius were to come back to

life today, no one apart from scholars could

understand what he was saying, but if he

scribbled a message people could read it

as easily as they could read a shopping

list."

The

French like to say that "what is not

clear, is not French." The Germans

are convinced that their language has mystical

powers of clarity of expression.

In

many countries people use more than one

language . In Bangladesh apart from our

mother tongue we use English in higher courts

and in communications with foreign countries.

Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists use Arabic,

Sanskrit and Pali respectively for religious

purposes. There are about twenty languages

spoken by our indigenous peoples. In East

Africa, apart from local languages and English,

a large number of people speak Swahili.

In West Africa apart from local languages

and English or French a large number of

people speak Hausa.

In

Luxemburg the inhabitants use French in

school, German for reading newspapers, and

Luxemburgish, a local German dialect, at

home. In Paraguay, people conduct business

in Spanish, but make their jokes in Guarani,

the native Indian tongue.

Charles

V of Spain once said that English was the

language for conversing with merchants,

German with soldiers, French with women,

Italian with friends, and Spanish with God.

Hebrew

was once considered the perfect language,

because it was "obviously the language

that God spoke". For more than a thousand

years Latin held a position of honor in

Europe.

Amongst

the Hindus Sanskrit is regarded as the devabhasa,

the language of the gods. The sudras, the

lowest caste, were even forbidden to hear

Sanskrit, the language of the Vedas. Punishment

was prescribed for the violators. Hot lead

would be poured in the ears of the careless

listeners .

The

ancient Greeks felt that any language but

Greek was nothing but mere babbling, the

literal meaning of word barbaroi,

"barbarian". During the heyday

of their Empires the English, the French,

the Spaniards and the Portuguese felt the

same way about their languages.

In

the present-day world American English speakers

outnumber British English speakers by almost

four to one and all speakers of English

variants around the world by nearly two

to one. American and not British English

has come to dominate the global linguistic

scene. Comparisons and contrasts of the

two versions of English have gone on for

years. To most Americans British accent

is "Highfalutin". To most British

American English is crass.

Language

conflict occurs when there is a competition

between languages for exclusive use in the

government or as the medium of instruction

in educational institutions. In countries

where two or more languages coexist confusion

often arises. In Belgium many towns have

two quite separate names, one recognised

by French speakers, one by Dutch speakers.

Language is often an emotive issue in Belgium

and has brought down governments. In Canada

the Anglophiles and Francophiles are fighting

a long drawn battle for identity and supremacy.

After

the demise of the Union of Soviet Socialist

Republics there has been a linguistic rejuvenation

in some of the former Soviet republics .

The languages like Armenian, Estonian, Georgian,

Latvian, Lithuanian and Ukrainian became

the source of inspiration and assertion

for the new nations. In central Asia Muslim

republics like Azerbaizan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan

and Uzbekistan abandoned the Cyrillic script

of Russian and opted for the Western script

of their Turkish kinsmen. Tajikistan adopted

the Arabic script.

In former Yugoslavia the Serbs started to

call their language Serbian rather than

its earlier name Serbo-Croatian and opted

for the Cyrillic script of their Russian

kinsmen . Croats now call their language

Simplyn Croatian and is engaged in purging

itself of Turkish and foreign words. Bosnians

tried to avidly borrow Turkish and Arabic

words.

It

is for their intense love for their languages

that the Czechs and the Slovaks got themselves

separated.

In Turkey there was an attempt to cleanse

that language of Arab- Persian words. When

that plan was found to be difficult Kemal

Ataturk gave the Sun-God theory and explained

that the Turkish language like the sun was

the fountainhead of all languages and the

borrowed foreign words were Turkish in origin.

Professor

Joshua A. Fishman has suggested that a language

is more likely to be accepted as lingua

franca or a Language of Wider Communication

(LWC) if it is not identified with a particular

ethnic group, religion or ideology. Like

Akkadian, Aramaic, Greek and Latin English

has recently been de-ethnicised. Professor

Joshua has said, "It is part of the

relative good fortune of English as an additional

language that neither its British nor its

American fountainheads have been widely

or deeply viewed in an ethnic or ideological

context for the past quarter century or

so."

Samuel

P. Huntington in The Clash of Civilisations

and the Remaking of World Order said that

"English is the world's way of communicating

interculturally just as the Christian calendar

is the world's way of tracking time, Arabic

numbers are world's way of counting and

the metric system is, for the most, the

world's way of measuring. The use of English

in this way, however, is intercultural communication;

it presupposes the existence of separate

cultures. A lingua franca is a way of coping

with linguistic and cultural differences,

not a way of eliminating them. It is a tool

for communication and not a source of identity

and community."

There

is no reliable evidence to show that the

increasing proportion of the world's population

speaks English. Even today English is foreign

to 92 per cent of the people of the world.

Our Anglophiles must pay heed to the linguists

like Joshua. Fishman who has highlighted

the importance of local languages thus:

"Local tongues foster higher levels

of school success, higher degrees of participation

in local government, more informed citizenship

and better knowledge of one's culture, history

and faith….. the world's practical

reliance on local languages today is every

bit as great as the identity roles these

languages fulfill."

Fishman

did not forget to emphasise that "Nevertheless,

both rationalisation and globalisation require

that more and more of local languages be

multiliterate."

In

the Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger

of Disappearing,

Edited

by Stephen A. Wurm, published by UNESCO,

it has been pointed out that for various

reasons the fate of languages took a turn

for the worse in the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries. The geographical explorations

and the expansionist tendencies of some

European powers like Dutch, English, French,

Portuguese Spaniards and Russia and introduction

of new diseases like small pox in North

America, Siberia and later Australia were

responsible for the death and disappearance

of hundreds of languages over the past three

hundred years. According to one estimate

about half of the approximately 6,000 languages

in the world are now endangered to some

degree and other. According to another estimate

every two weeks a language is getting extinct.

Ethnicity

embedded in the love for a particular language

may be dangerously self-centred, intolerant

and malevolent and cause immense miseries.

There

are two views on the disappearance of languages.

One view is that the differences between

languages are only superficial as they are

ultimately saying the same thing in different

forms and that the disappearance of any

one language is a minor occurrence. The

other view is that different languages emphasise

and filter various aspects of multifaceted

reality in a vast number of different ways.

Every language reflects a unique world-view

and the linguistic diversity is an invaluable

asset and resource rather an obstacle to

progress.

There

is no primitive language any more than there

is any superior language. Every language

proves to be as sophisticated and complete

as any other. No language or dialect is

better or worse than any other. Each language

is much like a "linguistic ecology

"as it were. Since 1970s the latter

view is gaining ground and it has been reflected

in several international instruments.

Article

27 of the International Covenant on Civil

and Political Rights 1966 provides "

In those states in which ethnic, religious

or linguistic minorities exist, persons

belonging to such minorities shall not be

denied the right, in community with other

the other members of their group to enjoy

their culture, to profess and practise their

own religion, or to use their own language."

Inspired

by the provisions of that article the Declaration

of the Rights of Persons Belonging to the

National or Ethnic , Religious or Linguistic

Minorities proclaims that States should

take appropriate measures so that wherever

possible, persons belonging to minorities

may have adequate opportunities to learn

their mother tongue or to have instruction

in their mother tongue.

In

the Draft Declaration on the Rights of the

Indigenous Peoples 1995 it was affirmed

that all peoples contribute to the diversity

and richness of civilization and cultures

which constitute the common heritage of

human kind.

Following

a proposal made by Bangladesh ,UNESCO created

International Mother Language Day in 1999.

Twenty- First February was chosen in commemoration

of the language movement in which five students

died on this date in 1952 defending recognition

of Bangla as a state language of the former

Pakistan, the eastern part of which became

Bangladesh after the war of liberation.

It is now acknowledged that a culture of

peace can only flourish where people enjoy

that right to use their mother tongue fully

and freely in all the various situations

of their lives. With love for all languages

we assert today that in the galaxy of languages,

every word is a star.

......................................................

The author is former Chief Justice and

head of caretaker government.

Preserving

and rejuvenating the heritage

Dr.

Syed Saad Andaleeb

....................................................

Each year February 21st arrives with a flourish;

and it awakens something special in many

of us. Some suddenly become conscious of

their distinct identity and proud heritage

of being a Bengali; some don the traditional

kurta or the taant sari to "feel"

Bengali; some prepare pithas and panta bhaat

for that fleeting Bengaliness. Others make

the effort to go to the Shahid Minar early

in the morning -- flowers or garlands in

hand -- to pay tribute to Rafique, Barkat,

Salaam, Jabbar and others who immortalised

a day that is, or should be, dear to Bengalis

all over the world.

Some

join the procession of men and women, young

and old singing a sombre Amaar Bhaiyer Rokte

Rangano…, while a few of the last

remaining stalwarts stand back from the

crowd remembering that special day, misty

eyed -- perhaps a teardrop rolling down

their cheeks to be briskly wiped away --

as they are overwhelmed with an emotional

surge for simply having been there as part

of a metamorphic event on that fateful day

that is now symbolised as International

Mother Language Day.

One

needs to sit back and think what it all

means: We Bengalis have carved out an entire

day by making the greatest sacrifice to

stand against oppression and injustice,

to stand for a distinct identity, and to

enjoy a freedom to bask in a soul -- the

Bengali soul -- that can be best understood

with the Bengali language. Any other language

trying to depict the Bengali soul would

certainly be weaker in that endeavour because

there is something about grambangla, matir

manush, godhuli logno or swarnali shondhya

that simply cannot be portrayed fully by

any other language. This very special language

is our heritage, our link to the past.

Today

this rich language -- rich in culture, religion,

history, absorbing stories, myths, struggles,

hopes and dreams, love and hate, family

and children, and so much more -- is under

attack. Like products and brands vying for

customer attention, the Bengali language

seems to be losing customers and market

share to its competitors. And if we allow

our competitors to gain ground, surely we'll

cast away our heritage as an obsolete product

in the stockpile of embattled products of

another era.

The

prognosis seems dire for when 21st February

will have come and gone most of us will

slide back into "reality." The

Bangla books we purchased during Boi Mela

will begin to gather the first microns of

dust, the Z-TV, Star Cinema, ATN, or Kasoti

will come back with a vengeance, the rush

to admit children to English medium schools

or Madrasahs will gather momentum (not that

learning another language is undesirable),

the desire to impress our foreign friends

in their language (Urdu included) will pick

up steadily although the reverse is most

unlikely to happen, and the desire to learn

about other cultures -- Delhi, Bombay, Bangkok,

Singapore, London, Paris, New York, or perhaps

even Timbuktu -- will take us away for the

weekend or an extended sojourn. And on our

return we'll have grand stories to tell

about the Louvre Museum, the Taj Mahal,

the Fontana Trevi, The Empire State Building,

St. Peter's Cathedral, or the palaces and

castles of Vienna and Scotland, and so on.

All the while the keeper of the Bengali

soul, its very own language, once vibrant

in its classy character and pristine beauty,

will languish and diminish in stature, impoverished

for want of attention and nurture.

Is

this what we want -- to lose such a rich

heritage? Do we want to cast this glorious

language among the endangered species, perhaps

soon to become extinct? I do not know, but

we certainly need answers. At the same time

we need to preserve our heritage, foster

its revival, and see it flourish for our

sake, for our children's sake. How are we

going to accomplish this?

First

and foremost, we must "preserve"

what we already have before we lose it to

time and relentless competition. That, by

itself, is a monumental task and needs a

small but dedicated army. I cannot help

but observe with envy how the younger generation

from neighbouring India -- many of them

born outside the country of Indian parentage

-- is returning to the land of their ancestors

with a burning desire to learn about their

own heritage and to preserve what they believe

is being lost to time and lack of attention.

One such project explores how the Vaisnava

thinker -- Ramanuja -- transformed the Vedanta

system into a theistic system called Visistadvaita

Vedanta. Another explores how Indian women

are rewriting history by confronting the

legacy of women's silence and voicelessness.

A young man is busy researching and creating

a series of illustrated children's (comic)

books based on indigenous Hindu folktales,

while a young woman is busy collecting and

documenting Jain miniature paintings in

Jaipur from the homes of rich families and

private collectors.

Through

various scholarship programmes from the

Indira Gandhi Foundation, the Fulbright

Programme, funds from the University of

Chicago, and other sources, India is also

encouraging non-Indians to pursue projects

such as collecting the works of Sir Syed

Ahmed Khan, especially how he worked to

improve the status of Indian Muslims during

the British rule.

We

must learn from these initiatives and inspire

our own youth to engage in similar journeys

to re-discover the Bengali soul, for they

are our next generation and will have to

become the guardians of the Bengali soul

and heritage.

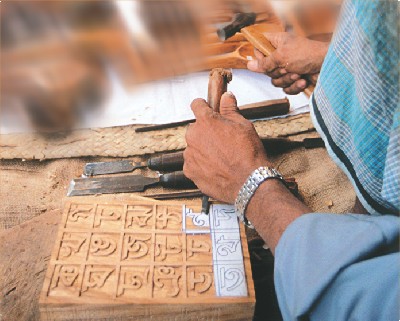

Preservation

of what we have, however, is the first step;

rejuvenating the language and seeing it

flourish so that it can withstand the competitive

onslaughts is clearly another vital need.

For this to happen we need a clear vision

from an enlightened and visionary leadership

backed up by a firm commitment to engage

in and do what is realistically possible.

The vision must include our cultural ambassadors

-- the poets, the painters, the scholars,

the singers, the musicians, the bards, the

artisans, the curators, the librarians,

the photographers, the linguists, the historians,

the archaeologists, the cinematographers,

the playwrights, the actors, the media men

and women, the teachers, and related others

-- whose stature in society must be upgraded

by their own doing and societal intervention.

And they must discard petty politics of

their own and all that comes with it to

form a true partnership to "preserve

and enrich the heritage."

Resources

will also be needed for such a grand project

that ought to be raised from both home and

abroad. In India today there are many heritage

sites that are being revived by foreign

funds "interested" in their preservation

or by NRIs (non-resident Indians) intent

on "giving back" to their roots.

These strategies can be emulated, albeit

on a smaller scale initially.

All

we need now to begin the preservation and

revitalisation project is a leadership that

understands the priorities, sets the vision,

and implements it in a manner that harnesses

all Bengalis in a spirit of cooperation,

harmony, and a burning desire to reclaim

the stature of a language from a region

about which it was once said, "What

Bengal thinks today, India thinks tomorrow."

......................................................

The author is Editor of the Journal

of Bangladesh Studies, and a Fulbright Scholar

at East-West University.