Feature

Learning from building with earth

Md. Shoeb Al Rahe

IT was while taking a Rural Architecture course in our fourth year at the Department of Architecture, BRAC University that I first realized that this was the area in our profession that interested me most. We were asked to go back to our own individual villages and study the socio-economics and architecture of the place. I discovered in my village that illiteracy, poverty and many other social problems were becoming a hindrance to progress and development for the people. I realized the scope of our work went far beyond the mere arrangement of space and functions. IT was while taking a Rural Architecture course in our fourth year at the Department of Architecture, BRAC University that I first realized that this was the area in our profession that interested me most. We were asked to go back to our own individual villages and study the socio-economics and architecture of the place. I discovered in my village that illiteracy, poverty and many other social problems were becoming a hindrance to progress and development for the people. I realized the scope of our work went far beyond the mere arrangement of space and functions.

Some months later, I met Anna Heringer for the first time. Anna Heringer and Eike Roswag, architects from Germany, and Dipshikha, one of the NGOs in Bangladesh had recently won the Aga Khan award for Architecture, 2007 for designing METI school in Rudrapur, a remote village in Dinajpur. Anna came to a lecture at Chetana, a group that meets weekly to talk about architectural issues and I went to listen to her talk about her work. Inspired and intrigued by the novelty of what she was trying to do, on an impulse I told her that I would like to work with her sometime. She said she would let me know if something came up. Only a few months later in September 2007, a group of student volunteers from the Department of Architecture, BRAC University, under the guidance of our teacher, Khondaker Hasibul Kabir, went to Rudrapur village in Dinajpur where the METI school complex was being extended. I went there along with my friends, Imrul Kayes, Omar Faruque, Gazi Md Fazle Rahim, Adrita Anwar, Majeda Khatun, Tanmay Chakrabarty and Shuvasis Saha and 5 Austrian architecture students. We began what would be one of the most defining experiences of my life.

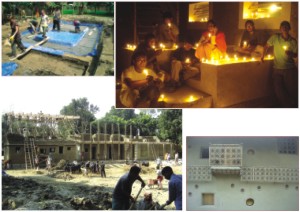

The work was very demanding. During the day we had to work with the labourers; cutting the earth and preparing it for construction, which was backbreaking work. In the evenings, instead of resting like the labourers, we had to work on the designs of the few houses we were building in groups. Coordinating the design process and the physical work was difficult to adjust as our work as students and in architectural practice here in the city was very different.

The five Austrian architecture student volunteers added another dimension to our communications. They came with their own concepts and ideas about what they wanted to do and were not always consistent with what we wanted. It took us a while to get on the same wavelength before we could all coordinate our efforts.

Once everything was organized between us there were problems in dealing with the clients - the villagers for whom we were designing and building the houses. They had fixed ideas about how houses should look and be built and it took some time to explain to them what would be ideal for us to do. Sometimes, when we designed a particular feature for one of the houses, for example, circular windows, and the client agreed with us, all the other clients wanted the same thing. They began to think that that was the best option for them, whereas our aim was to try something different at every one of the sites. Finally, when all was settled, our work was still heavily dependent on the all-encompassing factor- the weather. Once everything was organized between us there were problems in dealing with the clients - the villagers for whom we were designing and building the houses. They had fixed ideas about how houses should look and be built and it took some time to explain to them what would be ideal for us to do. Sometimes, when we designed a particular feature for one of the houses, for example, circular windows, and the client agreed with us, all the other clients wanted the same thing. They began to think that that was the best option for them, whereas our aim was to try something different at every one of the sites. Finally, when all was settled, our work was still heavily dependent on the all-encompassing factor- the weather.

Sometimes, when we had everything ready to begin work, we would be delayed by rain or a storm. This was disappointing but gave us a feel of how construction work was actually executed in the villages and the circumstances and situations that the builders have to deal with.

In addition to other duties, I had to oversee the smooth running of all processes on site, sometimes acting as interpreter between Anna and the workers, sometimes, finding ways to cut down the running cost of the work through time and resource management. We tried to stick to using local materials, sometimes even when they were not the best options in order to cut down on the carrying cost. For example, we opted for local bricks instead of good quality brick from Dinajpur town and local wood (Jam Kath) instead of Teak from the town. This saved a lot of time as well. The experiences taught me to not just work with earth and bamboo using local technology, as I had hoped, but also to work with people in real situations where sometimes our textbooks and formal education cannot come up with any answers. We have to then rely on sheer instinct and imagination.

While I was carrying out my work as manager in the DESI site the rest of my friends were carrying on with their own work on different sites. Omar, Mazeda and Shuvo were working on Hemonto's house, Imrul and Adrita on Shepal's house and Tonmoy and Gazi on Rohini's house. They were mixing mud constructing walls and floors. In our spare time we familiarized ourselves with the villagers, playing with the local children.

The METI School won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture and created an image that everyone was inclined to imitate. However, our objective was to learn from the first project and create different and even better solutions in the following projects. This was not always easy to follow given the impression that the METI School had already created an impression in the minds of all labourers, villagers and others concerned. In the METI School, nylon ropes were used to tie the bamboo joints. But it was found that scorching sun burns the nylon off the joints. So in the following project we used nylon along with coconut threads in the interiors as much as possible and used stainless steel wires for the exterior joints. We also gave considerable thought to landscape design which was also new to Rudrapur. We involved the DESI and METI school students in the process to give them a sense of ownership.

Through the project, we found the people of rural Bangladesh to be very simple minded, honest and receptive in nature.

Most of them have no formal education and learnt their skills through working with others in the trade and they are always open to new ideas, sometimes more than their educated, urban counterparts who are too aware of too many trends to take risks and explore new ones. If one can truly make these villagers understand the overall impact of the work on developing the villages or taking the place forward into the future, they are willing to put everything into their work to make it successful. Intermingling with the villagers, listening to their problems and learning from their experiences, without trying to impose our ideas on them made them comfortable to share with us their knowledge and skills and receive what we had to offer in design and thought. It is not a coincidence that Bangladeshi rural architecture has come to survive time, natural disasters and many other hurdles to come to a state of perfection, albeit a temporary one. The labourers, masons, wood workers, earth cutters, potters and bamboo workers of Rudrapur and Dinajpur have been working with these materials for generations on end and have gained an expertise that we can only hope to achieve someday. Their ancestors have designed the terracotta tablets of the Kantajeer Mandir. They have so far only known to work in a particular traditional manner but given the right direction and training, their skills could be developed to produce incredible results for the future. Most of them have no formal education and learnt their skills through working with others in the trade and they are always open to new ideas, sometimes more than their educated, urban counterparts who are too aware of too many trends to take risks and explore new ones. If one can truly make these villagers understand the overall impact of the work on developing the villages or taking the place forward into the future, they are willing to put everything into their work to make it successful. Intermingling with the villagers, listening to their problems and learning from their experiences, without trying to impose our ideas on them made them comfortable to share with us their knowledge and skills and receive what we had to offer in design and thought. It is not a coincidence that Bangladeshi rural architecture has come to survive time, natural disasters and many other hurdles to come to a state of perfection, albeit a temporary one. The labourers, masons, wood workers, earth cutters, potters and bamboo workers of Rudrapur and Dinajpur have been working with these materials for generations on end and have gained an expertise that we can only hope to achieve someday. Their ancestors have designed the terracotta tablets of the Kantajeer Mandir. They have so far only known to work in a particular traditional manner but given the right direction and training, their skills could be developed to produce incredible results for the future.

The writer is a graduate of the Department of Architecture, BRAC University.

Answer

|