Feature

An Architect's Dhaka

Part Nine

Dr. Mahbubur Rahman

THE Ahsan Manjil in Kumartoli, the most splendid architectural landmark in Dhaka besides the Sangshad Bhaban, crowns the river bank in the oldest part of the city. The building, aka Pink Palace because of its colour, caught the fancy of Alimullah who had a tendency to appropriate personal artefacts of the royalty and saw himself in the image of the majestically reposing Mughals. THE Ahsan Manjil in Kumartoli, the most splendid architectural landmark in Dhaka besides the Sangshad Bhaban, crowns the river bank in the oldest part of the city. The building, aka Pink Palace because of its colour, caught the fancy of Alimullah who had a tendency to appropriate personal artefacts of the royalty and saw himself in the image of the majestically reposing Mughals.

Sheikh Enayetullah, a zamindaar from Jalaldi, Faridpur, built a Rangmahal. The French merchants in Dhaka bought it from his son Motiullah and used it till 1830. Alimullah acquired it in 1838 to reside there. His son, Ghani Miah, who was later given the title of Nawab, among more to come, by the British mainly because of his stand against the 1857's Sepoy Revolt, engaged Martin and Co. of Kolkata in 1859 to make an extension to the mansion. The new structure, completed in 1872, was named Ahsan Manjil after his son. It became the Rangmahal and the older one the Andarmahal, connected by a covered wooden bridge.

In 1888 a tornado severely damaged and burnt down the buildings, which were rebuilt and the new one was crowned with a high dome. The 1897 earthquake badly damaged them, felling the dome. Once again these were repaired by the Nawab, while the family stayed at Dilkusha. As zamindari was abolished (1952), the family shifted to Paribag, and various low-income stakeholders rented the complex out. They even walled up many spaces and reduced it to a slum.

The Anglo-Indian styled Ahsan Manjil was influenced by the colonial bungalow in plan and a Neo-Classical facade. A lantern dome popular in England was added; the original roof was raised at the centre, along a small gable at the middle of the south facade. The older Andarmahal bears arched colonnaded and Palladian windows. Literature makes no reference to its original style; perhaps renovation completely stripped off the original features. The buildings stand as perfectly symmetrical rectangles after the modifications, their neo-classical facade harmonises the wings.

A rotunda with an octagonal drum supporting the dome over it is at the centre of the symmetrical rectangle plan of the Rangmahal on the upper level. On the west next to it are a wooden floor ballroom and a guest room. The east has an audience hall, followed by a guest room and a card room. A flight of steps leading from the south lawn into the upper lobby over the porch and through a three arched portal was added to provide access from the Buckland Bundh. Dignitaries taking this entry would be given Guard of Honour. At the lower level that looks like a podium, a billiard room and a dining room are symmetrically arranged. It has vehicular access from the north too. The first floor has arched colonnades with Corinthian capitals; the lower level pilasters are Ionic. The parapet is surmounted with kiosks.

The building deserved preservation because of its historic value, emotional attachment of the Dhakaites, prominence as a landmark on the riverfront, and due to the outstanding Ango-Indian style. The Manjil's historicity lies in its being the seat of socio-political leadership of Muslim Bengal and the centre of colonial urban development in Dhaka. Patronised by Nawab Salimullah, many activities leading to the emergence of Pakistan centred in Ahsan Manjil the cradle of all India Muslim League. Colonial rulers on Dhaka visit spent time here. Governor General Lord Northbrook attended a function in the mansion as he laid the foundation of the water works sponsored by Nawab Ghani (1874). Lord Dufferin enjoyed its hospitality (1888). Lord Curzon stayed in the mansion to drum support for the proposed partition of Bengal (1904).

In 1970, the government wanted to use the Manjil as a Children Hospital, but found the dilapidated structure unfit. But its heritage value was evident and the committee recommended it for conservation. Recognising the landmark building's historical importance, the Public Works Secretary revived the proposal in 1975, by requesting the DIT to explore the possibilities of acquiring the complex and set up a museum after preservation. He formed a committee comprising the DIT Chairman, the Chief Architect, the Director of Urban Development and the Museum Curator, and sat with the Manager of the Nawab Court of Wards, the Director of Planning and the Parjatan Corporation to prepare a project proposal. The group opined that the “Ahsan Manjil should become a tourist attraction showcasing the history, culture and life of the peoples in Bangladesh”.

Political changes got the project stalled for a decade until the President took a personal interest. The General who usurped to power had a romantic disposition. In November, 1985 acquisition of Ahsan Manjil and adjacent area was gazetted. The precinct had other properties, e.g. the Gol Talab (Louis's Nalla) an oval pond excavated by Ali Miah where members of the extended family lived, or the Andarmahal; yet the Rangmahal was restore first.

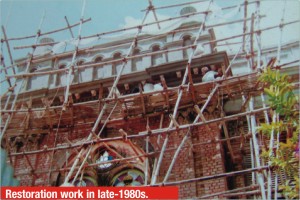

On March 16, 1986 the Government formed an Advisory Committee with the Education Secretary, Works Secretary, the National Museum Director, the Archaeology DG, the Chief Engineer and the Chief Architect; and engaged ASSO Consult to set up the exhibits following diorama, while the Department of Architecture carried out the conservation work; the site office was run by a principal architect. The premise had a number of private quarters for the ladies, later used as accommodations for less important nightly guests and essential staff. These and a stable were cleared out. The work was completed in July 1989 and the 23-gallery Museum was opened on September 20, 1992.

I first came to know about Ahsan Manjil possibly in the early 1970s when Bichitra did a story on it, urging for evicting the squatters and restoring the mansion. However, when it actually was happening in the late-1980s I was out of the country pursuing higher studies, and only returned to find a magnificent Pink Palace on the river. However, we architects soon got engaged in debates as to who should be credited with the Gold Medal that the Architects' Regional Council of Asia awarded the project in 1992, or whether pink was the right colour! The original lime-plaster finish of the building surface was replaced with sand-cement-lime plaster giving a reddish-pink lustre that monsoon rain washed away in a year; the weather beaten grey was ever present. Efforts were made more on giving the originally reddish-pink hue to the exterior, obtained by mixing the plaster with cement bound water based paint.

North South architecture students organised a workshop and month-long exhibition of measured drawings where the government Architecture Department presented their conservation efforts that renewed my interest on the building. I had long talks with the architects and consultants which were tapped by a colleague, and transcripts prepared by a student. Meanwhile at a party I met a Nawab family member who suggested I check a website on the Nawabs, full of rare photographs, history, biography and a fascinating family tree that connects thousands of people related to the family! My interest was heightened when the grandson of last Nawab Hasan Askari, studying at Berkeley College in Manhattan, defended a Jew from a

gang of ten thugs on the New York subway, who gave a Hanukah salute; Mayor Bloomberg handed down a crystal apple by Tiffany's as Foundation for Ethnic Understanding recognised Askari's altruism and bravery.

The Principal Architect who retired two years back thought he was chosen as the project required lot of on-site freehand drawings, and he was good at that. Yet before completion, he was transferred to Rajuk to undertake work on Ambar Shah masjid. Since there was no conservation architect with formal training in the country, there was a lot of amazing trials and errors. Books, references to the building, photographs and community elders were consulted to draw an image of the building during the time of the Nawabs. Some rare photographs were located at the British Museum which helped to reconstruct the interior.

The Nawabatkhana was moved near the east gate to be used as a souvenir shop. After measured drawings of the total building were prepared with details re-constructed from the parts that existed then, mock-ups of wooden details, mouldings, column capitals and decorative elements were made to test materials and craftsmanship in the PWD workshops, and then subcontracted to various manufacturers and/or suppliers.

Walls were redone in brick and damp proof courses were inserted, often by taking out a major part of it. Roof draining was introduced by adding tiger head gargoyles on roof drains to prevent dampening of the wall. Interior walls were originally finished with wall paper; new papers in matching pattern were imported from abroad.

Marble floors were replaced by locally available materials; sandstone was imported from Jaipur in India to replace the flooring in the verandas, driveways and the grand Chinitikri design was reconstructed in one of the bedrooms with the help of very old craftsmen. The main dining hall floor was originally done in a biscuit pattern; modern tiles matching the colour and design were cut to match their shapes and replace them.

The original roof and floor of the Ahsan Manjil was constructed with wooden joists covered with burnt clay tiles sealed with lime concrete. These were replaced with concrete floors and the ceiling was redone. The ballroom and the living room both had decorative false ceilings; these were preserved by carefully removing the lime terrace and inserting a layer of concrete cast with imported admixture. The surface was coated with sand and cement slurry to seal the pores and the entire surface was covered with concrete tiles. The false decorative ceilings were saved intact.

The missing metal railings and light posts were reconstructed by following community elders recollection of the design. Local shops were hired to replicate the cast iron models. The toilets with no plumbing used to be emptied by janitors, accessing by cast-iron stairs; remains of one such spiral stair was repaired and used.

Replacing wooden stairs from the northern veranda by cast-iron spiral stairs raised controversy as the original feature was removed to satisfy modern aesthetics, though many colonial period buildings show the presence of similar wooden staircases, confirming that these could be a part of the period design.

Coloured printed glass works were done in the companion metal doors of the main hall. Closest matching local coloured glasses were used to replace some of these damaged panels even though the difference between the existing original glass work and the later day additions is noticeable.

For the purposes of a Museum, concealed electrical wiring was installed in the interiors; exterior flood lights were set up to illuminate the building at night, as part of a lighting plan compatible in character with the old building. The boundary walls in metal railings were redone. The eastern gate was renovated and added with a brick paved road forming the main entrance, which originally was from the north that was marred by the construction of a market. The existing road from the north was replaced with a grassed landscape. Another illegally built shopping mall sprung up opposite the east entry of the complex.

The north gate eventually collapsed from encroachment on July 20, 2008. The Dept. of Archaeology listed this structure as heritage which they failed to protect. They however did not list the main complex as it was used by the Museum authority. Recently I was talking to a friend of mine who is the foremost conservation architect in Bangladesh. He thought leaving out the gate was wrong as a conserved gate would have opened up the whole complex to the city with far-reaching consequences, which now only faces the river!!

|