Last & Least

Heliopoetics

Dr Binoy Barman

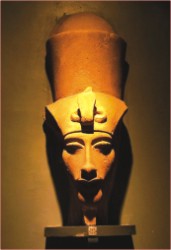

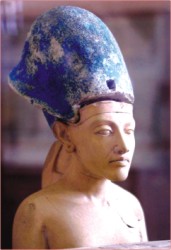

I love and respect Akhenaton, not because he is a king, but because he is a poet. He is in fact the earliest known king-poet in the history of the world. Akhenaton, better known as Amenhotep IV in the political history of ancient Egypt, ruled the land from 1379 to 1362 BC. He was an ardent worshipper of the god of sun (Aton) and changed his own name to 'Akhenaton', which means 'He who may serve Aton'. He brought about a religious revolution in Egypt, proclaiming that Aton was the one and only god, whose worship would be the national religion. He also built a new capital, Akhenaton (modern Tell-el-Amarna). He considered himself the son of Aton incarnate and the only human privileged to know the god. He explained the supremacy of Aton to his subjects, who used to worship their pharaoh. I love and respect Akhenaton, not because he is a king, but because he is a poet. He is in fact the earliest known king-poet in the history of the world. Akhenaton, better known as Amenhotep IV in the political history of ancient Egypt, ruled the land from 1379 to 1362 BC. He was an ardent worshipper of the god of sun (Aton) and changed his own name to 'Akhenaton', which means 'He who may serve Aton'. He brought about a religious revolution in Egypt, proclaiming that Aton was the one and only god, whose worship would be the national religion. He also built a new capital, Akhenaton (modern Tell-el-Amarna). He considered himself the son of Aton incarnate and the only human privileged to know the god. He explained the supremacy of Aton to his subjects, who used to worship their pharaoh.

As a pharaoh of Egypt, Akhenaton wrote poetry, devoted to his godfather, the sun-god. His poetry not only carries historical value but also immense aesthetic value. His verse lines were inscribed in hieroglyphs, which may still be read, in original, if one has the knowledge of pictographic script. However, one may also read them now in translation and derive the pleasure of poetry. His poetic genius is manifest in famous “The Hymn to the Aton”, in which he praises the sun for his support of life on earth. Here I will present a little analysis of the poem.

The poem makes its theme the glowing adoration of a devotee to his supreme lord. The speaker of the poems projects the echo of writer's voice. The writer, the king-poet, regards the god of sun as the protector and the savoir of earth and its dwellers. Aton has created all things, visible and invisible, animate and inanimate, in water, ground and air, in the universe. He is comparable to none. The poet says (as translated in The Ancient Near Eastern Texts edited by James B. Pritchard):

“How manifold it is, what thou hast made!

They are hidden from the face (of man).

O sole god, like whom there is no other!

Thou didst create the world according to thy desire,

Whilst thou wert alone: All men, cattle, and wild beasts,

Whatever is on earth, going upon (its) feet,

And what is on high, flying with its wings.”

We may extract the spiritual philosophy of Akhenaton from his poem. His religion is monotheistic in nature. But this 'monotheism' is a little different from what we know it to be at present. In modern sense, monotheism is the belief in one god, who is the creator of the world, all heavenly bodies including the sun. But Akhenaton's monotheism is heliocentric, i.e., based on the power of the sun. Here the sun itself is the creator of the world. We may deduce from this that during his time, the astronomical knowledge was in a primitive stage. The sun was considered to be the locus of the universe -- the most powerful divine entity, akin to God, as may be found in later-day scriptures. Akhenaton's monotheism can better be termed as 'Henotheism' (Greek term meaning 'one god'), which stipulates worshipping a single god while accepting the existence or possible existence of other deities.

We get a beautiful description of sunrise and sunset in the poem. When the sun rises, the earth smiles with light. The sun pours its beauty in all objects on earth. “When thou art risen on the eastern horizon, / Thou has filled every land with thy beauty.” Beauty witnessed by vision is possible because of the presence of light. “Eyes are fixed on beauty until thou settest.” When the sun sets, the world is filled with darkness. People sleep in their houses with the apprehension of various dangers lurking around. The nocturnal creatures come out from their hidings. “Every lion is come forth from his den; / All creeping things, they sting.” Their worries are over at the daybreak; they are enlivened again. “Awake and standing upon their feet, / for thou hast raised them up.”

The poem not just expresses the emotions of a meditative poet but also enunciates the practical aspects of the relationship between life and nature. Sun is, in reality, the prime source of light on earth -- the basic energy which makes it possible for all living things to exist. “When thou risest, they live, they grow for thee.” Without support of the sun, the earth will be devoid of life. Having realised this fact, the intelligent beings must feel obliged to the sun for their survival. It is the most practical thought, the most practical philosophy. It is the evidence of scientific mind. In Akhenaton's time, the concept of 'one god' had not yet started to be abstract; it was still concrete. Abstraction is the story of later days when the preachers concealed god -- omniscient, omnipotent and omnipresent -- behind impenetrable mysticism. The tendency probably started with King David (1010-965 BC), who wrote many sublime psalms in praise of one abstract god, initiating the dominant Judaeo-Christian canon. With this abstraction, humans lost direct relationship with nature, for ever.

The poet categorically acknowledges the contributions of the sun to the sustenance of life, in all its diversity, on earth. The sun has a soothing effect on the atmosphere and its nature. All enjoy the blessings of light. Thus comes the merry utterance:

“All beasts are content with their pasturage

Trees and plants are flourishing

The birds which fly from their nests....

They live when they thou hast risen for them....

The fish in the river dart before thy face

Thy rays are in the midst of the great green sea.”

It becomes clear that life is too much dependent on the sun. Human propagation is possible as there is sun. “Creator of seed in women, / Thou who makest fluid into man.” The cycle of birth is maintained. Likewise, the cycle of seasons also takes place, thanks to the sun. “Thou makest the seasons in order to rear all thou hast made, / The winter to cool them, / And the heat that they may taste thee.” Sun is the pivot of life and all forms of activities.

The poem is rich in imagery and symbolism. The readers' mind forms vivid images of cosmic phenomena in all their hues. The senses are stirred with the lively description, by virtue of the musical quality of diction: “Thou art gracious, great, glistening, and high over every land.” “Rising in thy form as the living Aton, / Appearing, shining, withdrawing and approaching, / Thou madest millions of forms of thyself alone. / Cities, towns, fields, roads, and river -- / Every eye beholds thee over against them, / For thou art the Aton of the day over the earth.” One may just close the eyes and the total scene gets alive with sunny or starry sky. The readers cannot miss the beauty of metaphorical language: “Darkness is a shroud, and the earth is in stillness.” Nor can he fail to feel the nuances of symbolism: “When the chick in the egg speaks within the shell, / Thou givest him breath within it to maintain him.” Chick is the symbol of life and egg is that of the world. The poem is rich in imagery and symbolism. The readers' mind forms vivid images of cosmic phenomena in all their hues. The senses are stirred with the lively description, by virtue of the musical quality of diction: “Thou art gracious, great, glistening, and high over every land.” “Rising in thy form as the living Aton, / Appearing, shining, withdrawing and approaching, / Thou madest millions of forms of thyself alone. / Cities, towns, fields, roads, and river -- / Every eye beholds thee over against them, / For thou art the Aton of the day over the earth.” One may just close the eyes and the total scene gets alive with sunny or starry sky. The readers cannot miss the beauty of metaphorical language: “Darkness is a shroud, and the earth is in stillness.” Nor can he fail to feel the nuances of symbolism: “When the chick in the egg speaks within the shell, / Thou givest him breath within it to maintain him.” Chick is the symbol of life and egg is that of the world.

The poem makes use of some geographical, political and religious allusions, which however does not make it too heavy a burden for the readers. Two Lands (Upper and Lower Egypt), Syria and Nubia (Ancient Syria included present-day Syria, Lebanon, Isreal and Jordan; Nubia was an ancient kingdom in northern Africa that included parts of modern Egypt and Sudan), Nile (the main African river, thought to be divine for its contribution to the fertility of Egyptian land), Re (the original Egyptian sun-god), Nefer-kheperu-Re Wa-en-Re (another name of Akhenaton, meaning 'the son of Re') and Nefertiti (the wife of Akhenaton, the queen) -- all appear essential, not causing any opacity in reading. Akhenaton uses such lofty epithet 'Lord of eternity' to address Aton, who is his father. Akhenaton turns mystic when he says, “Thou art my heart, / There is no other that knows thee.”

From time immemorial humans have aspired to establish a direct relationship with God. This aspiration manifested itself in different patterns like establishing kinship with God (e.g. filialness), transcendental communication with God (e.g. dhyan or nirban), and the incarnation of God (e.g. abatar). In the Eastern traditions including that of Indian subcontinent, the last two phenomena are observed more than the first one, which is common in Middle Eastern traditions, making way to the West. Akhenaton adopted the first strategy by default of tradition. He proclaimed himself as the son of Aton the God (“who came forth from thy body”). Through this, he wanted, firstly, to elevate his status from human to god and secondly, to be immortal through mass worship. His first desire remained unfulfilled, but his second desire was fulfilled albeit in a different way. He has become immortal as a poet, through his everlasting work of art (“living and flourishing forever and ever”).

(The writer is Assistant Professor and Head, Department of English, Daffodil International University.)

|