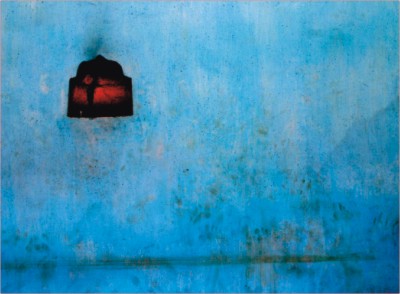

Inside

|

Essence and existence

Andaleeb Shahjahan compares and contrasts the joy inherent in Rabindranath's poetical mysticism with the transcendental despair of Western existentialism. Rabindranah Tagore in his lecture series titled Sadhana reminds us that: "From joy are born all creatures, by joy they are sustained, towards joy they progress, and into joy they enter." This belief is at the core of Eastern mysticism and philosophy. It recognizes ananda, or bliss, as the very foundation of human existence. Strictly speaking, this emphasis on the inherently joyous nature of existence is the hallmark of mystical Hinduism, of which the Kaviguru, as he was called by our national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam, was an ardent exponent. Even the teachings of Lord Buddha start off on a rather negative note, stating: "Life is suffering." Then he goes on to prescribe a dharma by which a human being can hope to escape this stranglehold. In fact, it is on this point, in the insistence on life as a suffering, as an absurdity, that Buddhism struck a sympathetic chord with many Western philosophers. Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus are two different voices of Western existentialism. However, Albert Camus, in his interviews, always objected to being put in the same category as Sartre, regardless of some of the common features they shared in their works. Camus, like Sartre, was an atheist, which made him ponder the miseries of human beings placed in a Godless world. But unlike Satre, he declared: "When I do happen to look for what is most fundamental in me, what I find is a taste for happiness. I have a very keen liking for people. I have no contempt for the human race […] At the centre of my work there is an invincible sun. It seems to me that all this does not make up such a sad philosophy." Indeed, it does not. It is this "happiness" that distinguishes him from Sartre's rather morbid philosophy. It is interesting to see that both start on the premise: "Existence precedes essence." Camus then veers off into a more positive direction. This premise is apparently the reverse of mystical Hinduism as epitomized by Rabindranath Tagore. But what unites them in the end is the struggle towards transcendence. Inherent in Rabindranath's mysticism is the idea of reincarnation, which Lord Buddha acknowledged, but Sartre denied. But the concept of reincarnation provides a clue as to what kind of circumstances a human being is placed in, in each lifetime and why. Since, for Sartre, this lifetime was the only one, his revolt against the unfairness of getting only one chance was that much more poignant. But in spite of all his "nausea" and "existential anguish," there was a willingness in him to transcend the crudity, the squalor, the apparent meaninglessness of life. After all, the bitterest critic, the cynic, and the satirist, although rather negatively, all assert the positive truth that life is supposed to be more beautiful than what it is. Otherwise, they would not rebel so vehemently against those elements of life that threaten peace, harmony, and joy. It is simply a negative way of saying that life is great. What glorifies their revolt is the fact that they refuse to be content with the easy happiness that comes with a certain amount of wealth and social status. Because they search for a deeper meaning, a more profound reason for living, they are philosophers. Both Satre and Camus thought human beings have to rise above the "mud," the "absurdity" into which they are plunged right from day one of their existence. Despair, in a world that is disconnected from God-consciousness, or sat-chit-ananda as Eastern mysticism calls it, is inevitable. The feeling of helplessness is almost paralyzing. Neither Sartre nor Camus could accept the handed down legacy of religion of their own times. Like our rebel poet, Kazi Nazrul Islam, they were rebels with a vengeance. Through their artistic creations, they exposed the hypocrisy of the society they lived in. When Christianity, as practiced in their society, failed to answer the deeper cries of their souls, they chose to abandon it with all their intellectual might. They did not wallow in despair, but rather used that all-consuming despair as an impetus to create a life of purpose, of meaning, and, finally, of transcendence. Camus said in an interview: "Accepting the absurdity of everything around us is one step, a necessary experience: it should not become a dead end. It arouses a revolt that can become fruitful." Unlike Franz Kafka, Camus's existentialism, and to a lesser extent Sartre's, was not one of total despair. But for both Camus and Sartre, this despair of life was an inevitable step. Camus wrote, rather optimistically, in one of his essays: "There is no love of life without despair of life." It is the sort of saying that one can truly appreciate the comfort of being safe and dry only after one has swum across a sea of troubles and tribulations. Sartre did not abandon hope completely, as is often supposed, but rather he abandoned the easy faith in God and a harmonious society. His vision was strong enough to penetrate the ugliness, the inanity, the banality of human existence, which like a veil, covers the emptiness, the nothingness inside every existence. Like a true individual, although still in a state of rebellion, he strove to create himself anew over and over again. Hence his famous saying: "I never stopped creating myself." This is the authentic voice of existentialism, at war against blind faith, the ready-made euphoria of the common man, but at the same time trying to transcend such hopelessness. However, Rabindranath's mysticism allowed him to see human beings, not as creatures thrust into the "mud," as Sartre believed, but as finite expressions of the Infinite. In his works of art, this is the keynote around which all other notes find their rightful place. For Rabindranath, essence precedes existence. He did not believe, like the existentialists, that human beings are empty slates at the time of birth, a tabula rasa. He, like so many other poets, believed in a transcendental reality from which we came and to which we will return after a brief sojourn on Earth. In fact, that is the core belief of Islam, Christianity, and Hinduism. But what gives an added beauty to this belief is Rabindranath's creative rendering of it. English romantic poets like Wordsworth, Coleridge, Blake, and Shelley (one of Rabindranath's favourites), or even American transcendentalists like Emerson and Walt Whitman, also struck the same note in their creative endeavours. This faith in a transcendental reality stems from a keen sensitivity to beauty all around us; beauty, which is the heart of creation. It is superior to any blind faith, because it recognizes evil as a legitimate reality, however impermanent. According to Rabindranath, evil is evil as long as it remains a fragment, disconnected from the totality of creation, and the source of creation. He, unlike the religious fanatics of our times, does not show the audacity to "uproot" evil simply because it too is part of God's plan, His lila. Where there is imperfection or fragmentation, there arises the need to strive towards perfection and a creative unity. That is the role of evil in human existence. Without darkness, there is no true appreciation of light. His mysticism is again superior to Sartre's existential freedom, because he realized freedom in bondage. To mystics, human beings are eternal souls who journey from lifetime to lifetime to arrive at the perfect knowledge of God, the Underlying Unity of all creation. Unless that knowledge has been attained, not through books or scriptures, but through personal experience, human beings feel "compelled to be reborn," to modify Sartre's declaration: "Human beings are condemned to be free." The eternal souls have to find their way back to freedom, not by denying bondage, because the soul encaged in a body will always experience a certain measure of bondage, but by learning to live with it. Within that bondage it is our freedom to be the best that we can be. Also without bondage, freedom has no positive meaning. Finally, Sartre, being skeptical of the mystical notion of ananda from which all creatures come into the world, always strove to create his individual identity in reaction to forces that threatened to crush his individuality. Cessation of his individuality meant "nothingness" to him. But for Rabindranath, cessation of personality meant the complete and final absorption into the Infinite, the eternal bliss. Absorption into bliss meant transcending a realm of duality, of alternating hope and despair, and entering the realm of the Absolute, the greatest of all mysteries. It is from this heightened awareness of human existence that our poet sang: "Ashbo jabo chirodiner shey ami (The eternal in me will forever appear and disappear)." He attained that pinnacle of human consciousness, like many prophets and rishis, where existence is not bondage, but a song of the Infinite, an endless play of appearance and disappearance. Andaleeb Shahjahan is a Copy Editor, The Daily Star. |