Inside

|

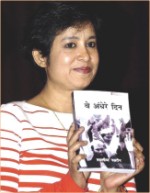

Taslima Nasrin: Woman in exile Agent provocateur or a bold voice of dissent against patriarchy? Rubaiyat Hossain re-examines Bangladesh's most controversial author.

Taslima Nasrin is a forbidden name in Bangladesh. No one likes her. Even the women's rights activists and female writers shy away from her. The validity of her political position as a woman, and the craftsmanship of her literary work have been questioned widely. I can understand the extreme resentment against her due to the strong oppositional position she has taken with regard to Islamic scriptures (or any religious scripture for that matter), but I keep thinking that there has to be something else in her writing, something else which has established her as an icon in the literary world. The iconification of Taslima Nasrin is covered with a negative hue. Her sexuality is always brought into question, and she is constructed as a thoroughly immoral woman who is doing crazy things just to get public attention. However, this is a very generalized, partial, and simplified understanding of Taslima Nasrin as a writer. When her recent book Dwikhondita (also known as Ka) came out I remember calling a book-store in New York in order to get a copy of the book. The store owner told me enthusiastically: "In this book, Taslima has named all the writers she has slept with." When I got the book and read it thoroughly, I was surprised when I reflected on the store owner's comment, since the book came across to me as nothing more than a very well-written emotional biography of a female writer trying to make it in a literary world mostly The book reveals Taslima's experiences of sexual abuse, and uncovers her relationships with prominent writers. It is the most accomplished of her literary pieces, but it still failed to draw any criticism based on literary lines. Almost all discussions of the book revolved around scandals, and Taslima's immorality as a woman. The wider level of reaction towards the book reveals the patriarchal double standards that reign over the culture of Bangla literature. It is very common for male writers to write about sexuality, in fact Sunil Gangopadhay's famous biographical travelogue, Chobir Deshey Kobitar Deshey, openly discusses his sexual experiences in the United States and Europe. Gangopadhay's biography does not bring into question his moral integrity because male writers are not only sanctioned to talk about sexuality, but writers like Sunil Gangopadhay, Shomoresh Boshu, and Buddhadev Bosu are acclaimed for talking openly about sexual experiences, thus ushering in a new state of modernity in Bangla literature.

It strikes me as a strange phenomenon, since most of Bangla literature, even pieces by Kalidasa, use women's bodies and sexuality as a prominent theme of rasa. The social approval for male writers to write about female bodies, and the imposed silence on women writing about their own bodies highlight the overall contour of Bangla literature where women are officially denied access to conceptualize, and write about, their own sexuality. When a woman writes, it is essentially different from a man writing, because women's personal experiences have a political implication. Women's personal experiences reveal the division, and implementation of patriarchal power through women's intimate experiences of sexual objectification. For example, the recent publication of Sylvia Plath's unabridged journals and unrevised version of her book of poems Ariel, with a forward by her daughter Frieda, informs us of Plath's extreme marginalization as a female poet, and her intimate experiences of sexual objectification in her marriage with poet Ted Hughes. Plath's work makes so much more sense when she is contextualized as a female poet fighting against the odds of 1950s patriarchal culture of the US and the UK. Virginia Woolf has pointed out that intellectual freedom depends on material things, and it informs women's psychological lives and their creative outcome. Esther, the protagonist of Sylvia Plath's novel The Bell Jar, sits down in front of her type-writer to write a novel and realizes that she cannot write, simply because she has "no experience." Domestic isolation, narrow social exposure, lack of access to material things to own a "room of their own" restrict women from writing about their unique experiences of objectification and marginalization. Woolf has also pointed out that telling the truth about one's experience as a body means "rejecting the ideal, pure image of woman." That is exactly what Taslima Nasrin has attempted to do in her literary work. Nasrin has flipped the use of womb from a place of reproduction to a place of resistance. The main protagonist of her novel Shodh uses her womb to give birth to an illegitimate child in order to take revenge on her husband. Whether or not this form of rebellion is desirable, or even empowering, is a separate debate. What I want to draw readers' attention to is Nasrin's alternative use of the female body, not only as a passive object, but as an active agent resisting an oppressive cultural code that masters women's bodies and reproductive organs.

It is a pity that men and women have shied away from benefiting from Nasrin's keen and sharp analysis of gender and power dynamics of women's sexual objectification. Her literary work creates a rupture in the episteme of patriarchal power-knowledge nexus, and opens up a space for the expression of female individuali but we have failed to take advantage of that space because the patriarchal media and literary circle have scandalized Taslima Nasrin to an extent that we do not even stop give her a second thought. We fail to acknowledge that Taslima Nasrin is actually a pretty good writer, and, in fact, she is the first one to openly speak up about issues of sexuality ranging from menstruation, sexual harassment, rape, masturbation, etc. It is not uncommon to read passages in Bangla literature about male masturbation, in fact a great literary link is established between the male sexual organ and his poetic exploration of imagery and emotions. Males are given the social approval to openly explore their sexuality and establish a link between their sexual experiences and the conceptualization of the world around them. Females, however, are totally condemned for writing about their own sexuality, which is symptomatic of the fact that society wipes out all agency from the hands of women in controlling their own sexuality, and puts it in the hands of the males. In order to claim one's space in society as a free agent, one must, primarily claim rights over one's own body. The NGO movements attempting to stop dowry, polygamy, or child-marriage do not cause a big stir in our social fabric, because those movements do not reach into the depths of patriarchal value and power system. Taslima, however, by claiming rights over her own body and sexuality, has shaken the core of our patriarchal value system. She has stepped out, and declared that she is not afraid to be called "fallen," because to be emancipated as a woman means in many ways to be recognized as "fallen" in our societal system. Rubaiyat Hossain is an independent film-maker and Lecturer at Brac University. |

You gave me poison.

You gave me poison. I want to argue that Taslima Nasrin is condemned, especially in the literary circle, because she is the first woman to talk openly about female sexuality in Bangla literature. She is also the first one to write openly about her sexual encounters with other writers (may they be true or fabricated). Whether Taslima's accounts in Dwikhondita were based on reality is an entirely separate debate, but from the ill reaction towards the book, we come to understand once again that when a female talks openly about her sexuality it is not well received.

I want to argue that Taslima Nasrin is condemned, especially in the literary circle, because she is the first woman to talk openly about female sexuality in Bangla literature. She is also the first one to write openly about her sexual encounters with other writers (may they be true or fabricated). Whether Taslima's accounts in Dwikhondita were based on reality is an entirely separate debate, but from the ill reaction towards the book, we come to understand once again that when a female talks openly about her sexuality it is not well received.  When Nasrin described a rape scene in Nimontron, many people found it to be completely obscene. In fact when I read it as a school-girl I thought it was a little too much, but now that I reflect back upon the book as a graduate student, I can finally find some relevance in actually spelling out the totally obscene, violent, and perverted lust that is being played out on women's bodies everyday. After all, why do we feel so uncomfortable reading a female writer writing about rape, when we are totally comfortable reading the newspaper reports on rape, mostly written by male reporters, which are sometimes not very far from being pornographic.

When Nasrin described a rape scene in Nimontron, many people found it to be completely obscene. In fact when I read it as a school-girl I thought it was a little too much, but now that I reflect back upon the book as a graduate student, I can finally find some relevance in actually spelling out the totally obscene, violent, and perverted lust that is being played out on women's bodies everyday. After all, why do we feel so uncomfortable reading a female writer writing about rape, when we are totally comfortable reading the newspaper reports on rape, mostly written by male reporters, which are sometimes not very far from being pornographic.