Inside

|

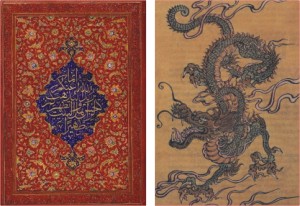

Islam now, China then: Any parallels?

"History is more or less bunk. It's tradition. We don't want tradition. We want to live in the present, and the only history that is worth a tinker's damn is the history that we make today."--Henry Ford On some days, a glance at the leading stories in the Western media strongly suggests that Muslims everywhere, of all stripes, have gone berserk. It appears that Muslims have lost their minds. In any week, we are confronted with reports of Islamic suicide attacks against Western targets in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, or Western countries themselves; terrorists foiled before they could act; terrorist attacks gone awry; terrorists indicted; terrorists convicted; terrorists tortured; terrorist suspects kidnapped by CIA; or warnings of new terrorist attacks against Western targets. Unprovoked, without cause -- we are repeatedly told -- Muslims everywhere, even those living in the West, are lashing out against the civilised West. Many in the Western world -- especially in the US -- are beginning to believe that the entire Islamic world is on the warpath against civilisation itself.

Expert commentators in the Western media want us to believe that the Muslims have lost their minds. They tell us that Muslims are inherently, innately, perverse; that never before has violence been used in this way, against innocent civilians. It is always "innocent" civilians. Other peoples, too, have endured colonisation, slavery, expulsions, extermination at the hands of Western powers, but none have responded with violence on this scale against the West. Certainly not with violence against civilians. Never have Aborigines, Africans, indigenous Americans, Hindus, Jews, or the Chinese targeted civilians. They never attacked Westerners indiscriminately. They never targeted "innocent Western civilians." Is this "insanity" slowly raising its head across the Islamic world really unique? Is this "insanity" a uniquely Islamic phenomenon? Is this a uniquely contemporary phenomenon? Is this "insanity" unprovoked? We cannot, of course, expect any history from the corporate US media on this Islamic "insanity." In order to take the moral high ground, to claim innocence, the rich and powerful -- the oppressor classes -- prefer not to talk about history, or invent the history that serves their interest. What is surprising, however, is that few writers, even on the left, bring much history to their analysis of unfolding events. Not being a historian -- of Islam, China or Britain -- I can only thank serendipity for the little bit of history that I will invoke to provide some background to the "malaise" unfolding in the Islamic world. A little history to connect Islam today to China in the middle of the nineteenth century. Implausibly -- perhaps for some -- the history I invoke comes from Friedrich Engels -- yes, he of the Communist Manifesto, friend of Karl Marx, revolutionary -- writing in May 1857, when the British were waging war against China, known to history as the Second Opium War. More implausibly, this history comes from an article published in a leading US newspaper, The New York Daily Tribune (available in Marx and Engels Internet Archive). Yes, in some remote past, a leading US newspaper routinely published commentaries by the likes of Marx and Engels. Today, the publishers of NYT, the <>Washington Post or LA Times<> would become apoplectic just thinking about it. During the First Opium War of 1840-42, when the British waged war to defend their "right" to smuggle opium into China -- Friedrich Engels writes: "The people were quiet; they left the Emperor's soldiers to fight the invaders, and submitted after defeat with Eastern fatalism to the power of the enemy." Yes, in those times, even enlightened Westerners spoke habitually of Oriental fatalism, fanaticism, sloth, backwardness, and -- not to forget their favourite -- despotism. However, something strange had overtaken the Chinese some fifteen years later. For, during the Second Opium War, writes Friedrich Engels: "The mass of people take an active, nay fanatical, part in the struggle against the foreigners. They poison the bread of the European community at Hongkong by wholesale, and with the coolest premeditation … They go with hidden arms on board trading steamers, and, when on the journey, massacre the crew and European passengers and seize the boat. They kill and kidnap every foreigner within their reach." Had the Chinese decided to trade one Oriental disease for another: Fatalism for fanaticism? Ah, these Orientals! Why can't they just stick to their fatalism? If only the Orientals would stick to their fatalism, all our conquests would have been such cakewalks! It was no ordinary fanaticism either. Outside the borders of their country, the Chinese were mounting suicide attacks against Westerners. "The very coolies," writes Friedrich Engels, "Emigrating to foreign countries rise in mutiny, and as if by concert, on board every emigrant ship, and fight for its possession, and, rather than surrender, go down to the bottom with it, or perish in its flames. Even out of China, the Chinese colonists …conspire and suddenly rise in nightly insurrection …" Why do the Chinese hate us? Friedrich Engels was not deceived by the moralising of the British press. Yes, the Chinese are still "barbarians," but the source of this "universal outbreak of all Chinese against all foreigners" was "the piratical policy of the British government." Piratical policy? No, never! We are on a civilising mission; la mission civilizatrice Européenne. It was not a message that the West has been ready to heed, then or now. Why had the Chinese chosen this form of warfare? What had gone wrong? Was this rage born of envy; was it integral to the Chinese ethos; was this rage aimed only at destroying the West? Westerners claim "their kidnappings, surprises, midnight massacres" are cowardly; but, Friedrich Engels answers, the "civilisation-mongers should not forget that according to their own showing they [the Chinese] could not stand against European means of destruction with their ordinary means of warfare." In other words, this was asymmetric warfare. If the weaker party in a combat possesses cunning, it will probe and fight the enemy's weaknesses, not its strengths. Then as now, this asymmetric warfare caused consternation in the West. How can the Europeans win when the enemy neutralises the West's enormous advantage in technology, when the enemy refuses to offer itself as a fixed target, when it deploys merely its human assets, its daring, cunning, its readiness to sacrifice bodies?

"What is an army to do," asks Engels, "Against a people resorting to such means of warfare? Where, how far, is it to penetrate into the enemy's country, how to maintain itself there?" The West again confronts that question in Iraq, Afghanistan and Palestine. The West has "penetrated into the enemy's country," but is having considerable trouble maintaining itself there. Increasingly, Western statesmen are asking: Can they maintain this presence without inviting more attacks? Friedrich Engels asked the British to give up "moralising on the horrible atrocities of the Chinese." Instead, he advises them to recognise that "this is a war pro aris et focis ["for altars and hearth"], a popular war for the maintenance of Chinese nationality, with all its overbearing prejudice, stupidity, learned ignorance and pedantic barbarism if you like, but yet a popular war." If we can ignore the stench of Western prejudice in this instance, there is a message here that the West might heed. Is it possible that the Muslims too are waging a "popular war," a war for the dignity and sovereignty of Islamic peoples? In 1857, the Chinese war against Westerners was confined to Southern China. However, "it would be a very dangerous war for the English if the fanaticism extends to the people of the interior." The British might destroy Canton, attack the coastal areas, but could they carry their attacks into the interior? Even if the British threw their entire might into the war, it "would not suffice to conquer and hold the two provinces of Kwangtung and Kwang-si. What, then, can they do further?" The United States and Israel now hold Palestine, Iraq, and Afghanistan. How strong, how firm, is their hold? On the one hand, they appear to be in a much stronger position than the British were in China. They have the "rulers" -- the Mubaraks, Musharrafs, and Malikis -- in their back pockets. But how long can these "rulers" stand against their people? What if the insurgency that now appears like a distant cloud on the horizon -- no larger than a man's fist -- is really the precursor of a popular war? What if the "extremists," "militants," "terrorists," are the advance guard of a popular war to restore sovereignty to Islamic peoples? Can the US and Israel win this war against close to a quarter of the world's population? Will this be a war worth fighting, worth winning? Shouldn't these great powers heed the words of Friedrich Engels? Shouldn't they heed history itself. After nearly a century of hard struggle, the Chinese gained their sovereignty in 1948, driving out every imperialist power from its shores. Today, China is the world's most powerful engine of capitalist development. It threatens no neighbour. Its secret service is not busy destabilising any country in the world. At least not yet. Imagine a world today -- and over the past sixty years -- if the West and Japan had succeeded in fragmenting China, splintering the unity of this great and ancient civilisation, and persisted in rubbing its face in the dirt? How many millions of troops would the West have to deploy to defends its client states in what is now China -- the Chinese equivalents of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Jordan, Egypt, Pakistan, and Iraq? If Vietnam bled the United States, imagine the consequences of a quagmire in China? Would the United States prefer this turbulent but splintered China -- held down at massive cost in blood and treasure, with bases, client states, wars, and unending terrorist attacks on American interests everywhere in the world -- to the China that it has today, united, prosperous, at peace; a competitor, but also one of its largest trading partners?

At what cost, and for how long, will the United States, Europe and Israel continue to support the splintering, occupation, and exploitation of the Islamic heartland they had imposed during World War I? At what cost -- to themselves and the peoples of the Islamic world? There are times when it is smarter to retrench than to hold on to past gains. That time is now, and that time may be running out. The most vital question before the world today is: Can the United States, Israel, or both, be prevented from starting this conflagration? M. Shahid Alam is Professor of Economics at Northeastern University. He is author of Challenging the New Orientalism (2007).

|