Inside

|

Crime and Punishment Megasthenes traces the history of war crimes and bringing their perpetrators to justice Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus was a statesman of ancient Rome. In the historical context, he is not as pre-eminent as his illustrious son-in law Julius Caesar. A proverb or apothegm, the authorship of which is generally ascribed to him, has come down across centuries and is the motto of many courts and judges in different countries even today. Fiat justitia ruat coelum or "Let justice be done, though the Heavens fall." Administration or dispensation of justice is essentially -- but not exclusively -- the province of the judiciary; the executive or the government also has an important, if secondary, role to play. In criminal cases it is the executive which investigates and prosecutes; it has the discretion to commute sentences, and may even grant pardons. Piso's maxim should be appropriate for the judiciary rather than the executive; as no responsible government can equably ignore the consequences of the Heavens falling on an unwary populace.

War is an abomination, and war crimes are acts that are so unconscionable, so excessive and gross, as to be unacceptable even in war. Simply put, they are violations of the laws and customs of war. Such customs have existed since ancient times. In the epic poem of old, the Mahabharata, on the eve of the climactic battle of Kurukshetra, leaders of both sides met to draw up the rules of engagement. The laws of war have evolved over centuries, particularly since the middle ages. They serve to mitigate the horrors and rigours of armed conflict. The Hague and Geneva Conventions of the late 19th and early 20th centuries were the first formal statements of the laws of war and war crimes in international law. These clarified the customary laws of war, but essentially focused on the relationship between belligerent nations and military forces, without addressing the impact of war on the civilian population. There were no war crimes trials after World War I. Huge war reparations, though, were exacted from Germany. During World War II, and in the years leading to it, there was widespread and vicious abuse of human rights. These were not merely incidental to the purposes of war, but, in many instances, a deliberate policy and tactic. The Allied Powers agreed in the Moscow Declaration of October 1943 that members of the German armed forces responsible for atrocities would be brought back to the scene of their crimes and judged on the spot by the people they had outraged. It was also stipulated that major war criminals whose offences had no particular geographical location would be punished by a joint decision of the governments of the Allies. By that time the outcome of the war was not in serious doubt. Pursuant to the Moscow Declaration and other similar pronouncements, the Allied Big Four concluded the "Agreement for the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the European Axis Powers" in August 1945 in London. It provided for an International Military Tribunal in accordance with a charter that would regulate its constitution, jurisdiction and functions.

The Tribunal's jurisdiction, as defined in the charter, covered three categories of distinct but not unrelated offences: (1) Crimes against peace -- namely, planning, preparation or waging a war of aggression, or a war in violation of international treaties, agreements or assurances, or participation in a common plan or conspirsacy for the accomplishment of any of the foregoing. (2) War crimes -- which included violations of laws and customs of war, murder, deportation of slave labour, ill-treatment of civilian populations in occupied territories, wanton destruction not justified by military necessity, etc. (3) Crimes against humanity -- which included murder, extermination, inhumane acts

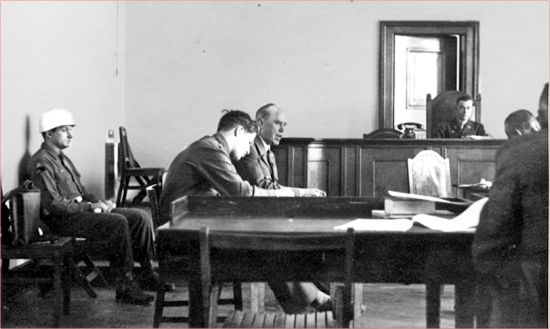

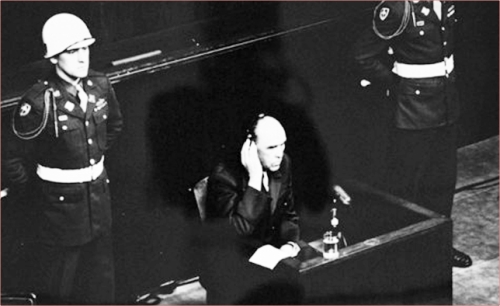

against civilian populations, enslavement, persecution on political, racial or religious grounds. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East was established by a separate proclamation in 1946. The object of the London Charter was, of course, to fortify and adequately equip the existing international framework for the war crimes trials. Some eminent individuals, learned in the law and who emphatically did not condone the Axis atrocities, however, were not comfortable with the form and procedure of the trials. Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court, Harlan Fiske Stone, felt that Justice Robert Jackson, the chief US prosecutor at the International Military Tribunal for Germany, was conducting a "high-grade lynching party in Nuremberg." Stone was not concerned about the fate of the accused Nazi leaders. He, however, considered the "pretense" that the Tribunal was a court conducted in accordance with the common law to be "too sanctimonious a fraud." In a similar vein, Justice William O. Douglas thought the Allies had substituted "power for principle" at the Nuremberg Trials, that unprincipled laws had been created ex-post facto to suit the passion and clamour of the time. Senator Robert Taft, whose father had served as president and chief justice of the US, was assured that the Nuremberg Trials represented "victors' justice," that they were a violation of the most basic principles of American justice and internationally accepted standards. Justice Radhabinod Pal of the Calcutta High Court was a member of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. His was a dissenting judgment; he found all defendants not guilty of Class A crimes, or crimes against peace. Pal had no illusions about Japanese war-time conduct. He simply was not prepared to apply laws that were created ex-post facto. Judgment of the vanquished by the victors, even if clothed in the garb of law, he felt, would not be impartial justice, but mere retribution. Justice Pal would later serve on the International Law Commission. The International Military Tribunals in Nuremberg and Tokyo tried the major war criminals, some fifty top echelon political, military, and economic leaders of Germany and Japan. Pursuant to a UN General Assembly resolution, the International Law Commission subsequently formulated the principles of international law that were recognised in the Charter of the International Nuremberg Tribunal and in its judgment. The Nuremberg Principles are a set of guidelines that determine what constitutes a war crime. There were thousands of war crimes trials, mostly by military tribunals in more than twenty countries of Europe, Asia, Australia, and the Pacific, for lesser war criminals. The four powers occupying Germany agreed that trials should also be held in each of the occupation zones. The London Charter did not provide for trials for alleged war crimes by Allied forces. There is perhaps a natural enough tendency not to apply the law for excesses against the enemy -- combatants and non-combatants -- too vigorously to one's own side in times of conflict. The Allied force had its share of "gung-ho" general officers. General Curtis LeMay was in charge of strategic air operations against Japan. The operations included incendiary attacks on cities and the fire bombing of Tokyo in the waning months of the war. LeMay fully expected to be tried as a war criminal if the outcome of the war had been different. War crimes trials were held in many tribunals in different countries. In retrospect, it would seem that the quality of justice meted out was not uniform, and that the severity of a sentence imposed was related as much to the enormity of the crime committed, as to the timing of the offender's capture and trial. Field Marshal Albert Kesselring (top, extreme left) was tried by a British military court in Padua and sentenced to death in 1947. The charges against him were ugly. He was accused of terrorising the local population by executions of hostages and civilians as reprisal against operations by partisans. The most infamous episode was the Ardeatine massacre: 335 Italian hostages were shot after an attack by the resistance, in which 33 German and Italian soldiers were killed.

Contrary to the Moscow Declaration, he was not handed over to Italian justice. Winston Churchill (top, middle), by that time the leader of the opposition, interceded with Prime Minister Attlee and sought clemency for Kesselring, as did an old adversary Field Marshal Alexander. Much earlier, Churchill, as prime minister, had mulled the feasibility of summary executions of top war criminals, which was legitimised subsequently by an Act of Attainder. War-time passions, however, had cooled, and Cold War considerations perhaps had begun to intrude. There would have been the realisation also that after conflict, reconciliation was the only constructive option. Kesselring's sentence was reduced to life imprisonment. He was in fact released in 1952. Field Marshal Von Rundstedt was charged as a war criminal by the British, for involvement in mass murders in Soviet territories. He never faced trial, ostensibly because of ill health. He was released in 1948 and died in 1952.2 Then there was Field Marshal Von Manstein (top, left). He was tried by a British Military Court in Hamburg in 1949 and sentenced to 18 years imprisonment, which was reduced to 12 years. He served 4 years before he was released for medical reasons. He had followed scorched earth tactics, denying food to the local population in occupied Soviet territories, and had failed to protect civilian lives.

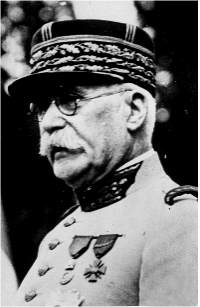

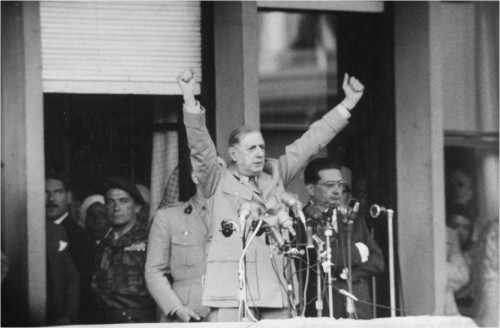

A particularly notorious outfit of war was Unit 731 of Japan. It conducted bacteriological research on humans, mainly Chinese and Russian prisoners, who were subjected to vivisection after being infected with various diseases. There were other grisly experiments. Thousands died. The object was to develop chemical and biological weapons. General MacArthur ensured immunity to those involved in such research, in exchange for valuable germ warfare data they had gathered. A number of Nazi doctors accused of human experimentation were, however, tried in US Military Courts; some were awarded capital punishment. Major Colin Powell was serving in Vietnam at the time of the infamous My Lai massacre in March 1968. Decades later, talking to Larry King on CNN, Secretary of State Powell observed that: "In war these horrible things happen every now and again, but they are still to be deplored." War crimes cannot perhaps be altogether separated from war. The term collaboration may be applied to actions ranging from urging the local population to extend support to an occupying power, to "traitorous cooperation with the enemy, criminal deeds in the service of the occupying power, complicity in murder, persecution, pillage, participating in a puppet government and economic exploitation." After World War II, collaborators were judged by their own countries and courts, often more harshly and with less ceremony than were Nazi war criminals. Many suspected collaborators received rough and ready summary justice. Thousands were charged with collaboration-related offences in countries like France, Norway, and Denmark. Marshal Petain (top, middle), a hero of World War I, was the head of state of Vichy France. After the war he was condemned to death for treason. General de Gaulle (top, right) commuted his sentence to life imprisonment, on account of both his advanced years and his past services to France. There were people to whom Petain was no collaborator, but the shield to De Gaulle's sword. Pierre Laval, the prime minister of Vichy France, had also held high political office before the war. He was found guilty of high treason after a hurried trial, and executed. Paul Touvier was found guilty of collusion and treason, and sentenced to death in absentia in 1946. He remained in hiding until pardoned by President Pompidou in 1971, a decision which incensed many Frenchmen. Fresh charges of crimes against humanity were leveled against him in 1973. Again he escaped and was not apprehended until 1989. In April 1994 he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Maurice Papon was a Gaullist politician. He was vested with the Legion of Honour by de Gaulle in 1961. In 1981, there were media reports that he had deported Jews to internment camps during the Vichy regime. Following a long investigation and legal battle, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison for crimes against humanity in 1998. He was released at the age of 92 for health reasons in September 2002. Robert Brasillach was a writer of promise, who, as the editor of a hard line fascist weekly, used his considerable skills to support Nazi policies and collaboration. He was tried in January 1945 for collaboration and condemned to death. A group of 59 eminent writers, including Camus, Mauriac, Paul Valery, Collette Cocteau, and Jean Anouilh, addressed a petition to Gen. de Gaulle seeking clemency for Brasillach. They did not share his politics, but felt that a civilised nation should not shoot its writers, more so when others more directly responsible for atrocities were treated lightly. De Gaulle declined to intervene. There were a few trials in Britain too. John Amery's father was a cabinet colleague of Churchill. The two were at Harrow at the same time. John was stridently anti-communist and pro-fascist. It was his brainchild that British POWs be recruited for a volunteer force to fight communists. He also made propaganda broadcasts over radio from Germany. He was found guilty of treason in 1945 and condemned to death. But Churchill did not seek clemency for the son of an old colleague. The story of William Joyce is similar. He had made propaganda broadcasts to Britain from Germany, and had also tried to recruit POWs for the so-called British Free Corps. He was executed for high treason in 1946.Certainly, the treatment of Brasillach, Amery and Joyce, differed greatly from that of Field Marshals Kesselring, Von Rundstedt and Von Manstein.

The British Raj considered members of the INA to be collaborators or war criminals, a view not shared by countless Indians. For them, the INA soldiers were patriots and heroes. There was a rare unity of views between the Congress and the Muslim League on the joint court martial of INA commanders Shahnawaz, Sehgal and Dhillon at the Red Fort. All three were found guilty, but the sentence of deportation for life was never carried out. In the waning phase of the Raj, such a sentence was neither feasible nor politic. Many believe that the INA trials, and its political effects, contributed significantly to a shift in British colonial policy in respect of India. War crimes trials for massive human rights abuses during the Liberation War in 1971 are not simply an academic or emotive issue for Bangladesh. The secretary general of Amnesty International, during her last visit to Bangladesh, expressed the view, in course of a talk, that such trials would be a vindication of human rights. The foreign affairs adviser, in a meeting with the UN secretary general earlier this year, broached the subject of war crimes trials. On December 16, 1971, the Pakistan Eastern Command surrendered unconditionally to Lt. Gen. J.S. Arora (right), the GOC of the joint Indian and Bangladesh forces in the Eastern theatre. Of the 93,000 Pakistani POWs, following thorough investigation, 195 were identified for trial on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The India-Pakistan Agreement of August 28, 1973, which addressed the humanitarian issue of repatriation of POWs, civilian internees and stranded persons, provided for the question of the 195 POWs to be discussed and settled at a tripartite meeting between Bangladesh, India and Pakistan. A foreign minister level The salient points of the agreement were: (2) The Pakistani foreign minister said that his government "condemned and deeply regretted any crimes that may have been committed." (3) The ministers noted that the prime minister of Pakistan had accepted an invitation to visit Bangladesh, and had declared that he would "appeal to the people of Bangladesh to forgive and forget the mistakes of the past, in order to promote reconciliation." (4) The ministers recalled the declaration of the prime minister of Bangladesh that "he wanted the people to … make a fresh start … that the people of Bangladesh knew how to forgive." (5) In the context of the foregoing, in particular the appeal of the prime minister of Pakistan to the people of Bangladesh to forgive and forget the mistakes of the past, the Bangladesh foreign minister conveyed the decision of his government "not to proceed with the trials as an act of clemency." It was agreed that the 195 POWs could be repatriated to Pakistan with other POWs who were being repatriated under the Delhi Agreement. (6) The ministers reaffirmed that the people of the three countries had a vital stake in peace and progress, and stressed the desire of their governments for normalisation of relations, and a durable peace. Incidentally, some friendly development partners -- who most certainly did not condone the war-time atrocities -- had been tepid to the idea of war crimes trials. Trials, they felt, would prolong tensions, make for complications and could also undermine Pakistan's newly revivified democracy. Instead a forward-looking policy, to promote and underpin cooperation and peace, would be to the benefit of all. In November 1973, Dr. Henry Kissinger went on his sixth trip to China. Extracts of declassified transcripts of his discussions with Prime Minister Chou En-Lai on November 11 afford some insights into the issue of war crimes trials in Bangladesh: Trials of collaborators are not linked to trials of war criminals, although the two are not unrelated either. If there is persuasive evidence that a person is guilty of criminal deeds, is involved or complicit in war crimes or crimes against humanity, he may certainly be subjected to the due process of law. In July this year, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, applied for an international arrest warrant against the president of Sudan (top) on charges of crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide in Darfur.

The pre-trial chamber of the ICC will consider the application. This is the first time such a warrant has been sought against an incumbent head of state. The responsibility of sitting in judgment is heavy, especially so in trials with political undertones. There can be huge complexities to contend with. The process of justice has to be credible and transparent, justice must be done and seen to have been done, and there should be allowance for the common weal. The UN secretary general has aptly stressed, in respect of the situation in Sudan, the need for a balance between the pursuit of peace and the duty of justice. A character in a Somerset Maugham short story made a very telling comment on the burden and dilemma of sitting in judgment. After recounting a particularly convoluted tale of human perversity, involving a very personable and companionable couple, he said wearily, somewhat cynically and even impiously: "I'll tell you what, there's one job I shouldn't like … God's at the Judgment Day … no sir." Megasthenes is an eminent Bangladeshi columnist. |

tripartite agreement between India, Bangladesh and Pakistan was concluded on April 9, 1974.

tripartite agreement between India, Bangladesh and Pakistan was concluded on April 9, 1974.