Inside

|

Manikganj revisited Marty Chen returns to find two villages thriving after thirty years

In mid-1975, at the request of Fazle Hasan Abed, I joined Brac to start its women's program. Abed and I had worked together with others in relief efforts after the November 1970 cyclone, and political lobbying for recognition of Bangladesh during the 1971 Liberation War. Started in 1972, to rehabilitate refugees who had fled to India during the civil war, Brac was a relatively small NGO in 1975: I was its 23rd. employee. In addition to the Sulla area of Sylhet district, its original area of operations, Brac had started activities in and around Jamalpur town in Mymensingh district and Manikganj town in Manikganj district. In November 1975, on a field trip to the Manikganj area, Brac colleagues and I met a group of women sitting in the shade of tree near a food-for-work site. The women had just been refused work at that site. Local officials turned them back, saying: "Women in Bangladesh should not work outside their homes. We have never hired women at food-for-work sites." The leader of this group of women was Saleha, the wife of a marginal farmer and mother of a young son and daughter. Over the next several months, Brac colleagues and I met other women who needed food-for-work in order to make ends meet: two of them were widowed mothers with young children, Boshiron and Shunabon. We also met a young deserted woman named Sufia who, presumably because she had studied to class 4, did not want to do manual food-for-work. From the end of June to early September 1974, Bangladesh had suffered severe floods. Reports of starvation began immediately after the floods, and grew in severity. The government of Bangladesh officially declared famine in late September. From early October to late November, the government operated langarkhanas (gruel kitchens) to provide free cooked-food to destitute people. Landless labourers (and their families) comprised the major share of those who were fed at the langarkhanas, or died of starvation. Estimates of how many people died in the famine vary greatly. What is clear is that, without the massive relief effort, the mortality would have been higher. By late November 1974, the government declared that the famine was over and closed the langarkhanas. But the effects of the famine dragged on. As one symptom of the lingering crisis, women continued to beg on the streets of towns and cities across the country. When the government (with international support) introduced food-for-work schemes throughout the country in late 1975 to provide additional relief, women came forward in record numbers. Women begging on the streets and seeking paid work outside their homes was uncommon in Bangladesh, where social norms have traditionally confined women to their homesteads or, if they need to seek paid work, to the homesteads of others in their villages. Bangladesh had a long history of food-for-work programs in lean employment seasons and after floods, drought, or other crises, but the participation of women was a new phenomenon. The government was simply not prepared to accept women into its rural works programs. Conditioned by tradition to believe women should not seek paid work outside their homes, local officials regularly turned them back. For the next five years, together with Aminul Alam and other Brac colleagues, I worked closely with Saleha, Boshiron, Shunabon, Sufia, and countless other women, organising local village organisations -- called Shramajibi Mahila Sangstha -- and promoting a set of livelihood activities -- including cow, goat, and poultry rearing; silk production; and embroidery and block printing. Since late 1975, much has changed for rural women in Bangladesh. The government of Bangladesh and food aid donors have promoted women's participation in food-for-work by recruiting them more actively, by reserving separate areas or tasks at all sites for women, by adopting separate payment norms for women, and by operating all-women sites. In addition, special food-for-work schemes for women, that involved less heavy lifting, notably roadside tree-planting and road maintenance schemes, have been introduced. Also, the World Food Programme and Brac developed a program whereby food aid was used to subsidise the start-up phase of poultry-rearing by women from poor households. Over the past three decades, hundreds of thousands of women have participated in the special women-only food-for-work schemes, and in the food-subsidised poultry scheme. More notably, since the mid-1970s, there has been a micro-finance revolution in Bangladesh, with rural women as the main clients. Over the past three decades, small loans have been extended to millions of poor persons and households in villages and slums: women represent the majority of the borrowers. Also notably, since the early 1980s, millions of rural women have been hired as workers in the export garment sector.

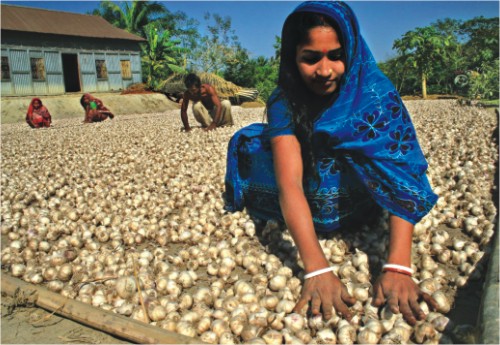

In late November 2007, with Aminul Alam of Brac, I revisited Manikganj to see how Saleha, Boshiron, Shunabon, Sufia, and the other village women we had begun working with in the mid-1970s, were doing. Some of the more dramatic changes in Bangladesh were visible on the drive from Dhaka city to Manikganj town: the urbanisation of the population marked by the massive expansion of Dhaka city in all directions, the industrialisation of the economy marked by the countless factories around the periphery of Dhaka, the construction boom marked by countless high-rise buildings, and the extensive sand dredging along the haurs and rivers to the west of Dhaka. As we left the industrial suburbs of Dhaka and Savar, the countryside became more rural and the drive more familiar: jute straw stacked near fields, jute fibre hanging to dry, fields-upon-fields in different shades of green interspersed, occasionally, with mustard yellow. Amin informed me that less-and-less mustard was being grown in Bangladesh, and that maize had replaced tobacco in the Manikganj area. After a quick cup of tea at the Ayesha Abed Centre on the edge of Manikganj town, where over 700 women (and some men) are engaged in block printing, screen printing, tie dyeing, embroidery, and tailoring for the Brac chain of Aarong stores. We turned off the main highway onto a country road. In the late 1970s, this road was roughly paved with brick. Horse carts and bicycles were the main modes of transport. Today, the road is surfaced with a tar composition. Motorcycles, bicycle rickshaws, and public buses are alternative modes of transport. In the late 1970s, there were no shops in the villages. Today, there are small grocery stores in some villages and small markets at some village cross-roads, with tailoring shops, and shops selling corrugated iron (CI) sheeting, food staples, and other daily necessities. In the late 1970s, most of the houses were made of mud and straw with thatch roofs -- CI sheeting for a roof was a luxury. Today, most of the houses are made of CI sheeting with cement floors; some are made of cement with CI sheeting roofs. In the late 1970s, all of the women wore plain blue or green saris with narrow woven borders, did not wear blouses, and went barefoot. Today, most of the women -- except very poor or widowed women -- wear colorful patterned saris with matching blouses and rubber sandals.

In the late 1970s, when Brac started its poultry programme, women raised local-breed chickens on a free-ranging basis. Today, many women raise improved breeds of chickens, both in coops and free-ranging, and there are poultry farms scattered throughout the villages. What has become of Saleha, Boshiron, Sufia, and Shunabon? The economic status of all of them has improved -- but to varying degrees. All of their homes are made from CI sheeting with cement floors. All of them have or had (until they became too old or frail to work) multiple sources of income, mostly Brac-sponsored productive activities. Saleha was an active -- indeed charismatic -- leader of her local women's association. Although she raised poultry and silkworms, Saleha remained more interested in political power and social status than in entrepreneurial activity, perhaps because she was married and her husband tilled their small plot of land until he died. Today, Saleha's married son, who lives next door, works in a Brac horticulture nursery; her married daughter lives nearby. Still strong and active, although in her 70s, Saleha laments the decline of her political power and social status when Brac shifted a local production center from her household to a larger plot elsewhere. Boshiron, widowed as a young mother with four young sons, was the most entrepreneurial -- taking up various Brac-sponsored productive activities, including poultry and silk rearing; investing her earnings in land to augment what she and her sons inherited from her late husband; and sharecropping out her land. She also became a leader, not only of the local women's association but also in her village. Now thin, frail, and in her 70s, Boshiron was once recognised as a female equivalent of the traditional elder (matbar), and called upon to give advice and settle conflicts. Two of her sons are rickshaw pullers, another works as a local program officer with Brac. The fourth son has twice migrated for work, first to the Middle East and then to the Maldives. Both times, Boshiron had to sell or mortgage land to pay the fees and bribes required for him to get a job abroad, yet both times her son did not send or bring home much of what he earned. Instead, he brought a burqa for his mother -- something, as a working poor woman in Bangladesh, she had never worn -- insisting that Muslim women in Bangladesh (like those he had seen in the Middle East) should wear burqas. Sufia, deserted as a young woman with a class four education, was in the first batch of block-printers trained by Brac. Today, she is remarried and supervises a Brac production center with 120 women block- and screen-printers. She was elected, and served one term, as a union council member, but did not stand for re-election as she found it too demanding to do both her Brac work and the union council work.

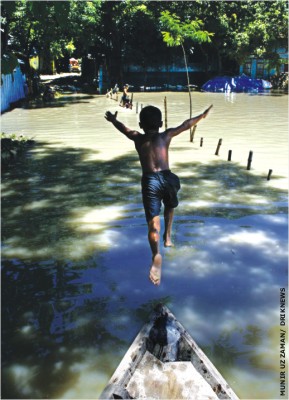

Clearly, life has improved in many ways for these women. But the chronic risks of rural Bangladesh persist: there were two major floods and a major cyclone in Bangladesh during 2007. The Manikganj area was flooded twice, but, fortunately, fell outside the trajectory of cyclone winds that destroyed crops across wide stretches of inland Bangladesh. Also, clearly, the fortunes of rural women in Bangladesh still depend on social norms and social ties. Although both were widowed with young sons, and both were entrepreneurial, taking advantage of what Brac had to offer them, Shunabon has fared better than Boshiron over the years -- in large part because her sons earn a steady income and maintain her. While social norms restricting women's mobility had eased, they appear to be tightening up again. Men who have migrated for work to the Middle East are now asking their female relatives back home -- like Boshiron -- to observe purdah and wear burqas. What this will mean over time for the ability of such women to work outside the home and play leadership roles in their villages is not clear. Marty Chen writes from Harvard University. |

I

I

When her husband died, leaving her with two young sons and a small plot of land, Shunabon sharecropped out the land and returned to her mother's village. She became active in Brac, serving as both a health worker and a poultry extension agent, and engaging in Brac-sponsored poultry rearing. She educated her two sons, who now jointly run a successful grocery store, and support her in her old age. Of the four women, Shunabon appears to have prospered the most, economically and socially: her dress and bearing suggest that she has become a lower middle-class woman with a degree of social status.

When her husband died, leaving her with two young sons and a small plot of land, Shunabon sharecropped out the land and returned to her mother's village. She became active in Brac, serving as both a health worker and a poultry extension agent, and engaging in Brac-sponsored poultry rearing. She educated her two sons, who now jointly run a successful grocery store, and support her in her old age. Of the four women, Shunabon appears to have prospered the most, economically and socially: her dress and bearing suggest that she has become a lower middle-class woman with a degree of social status.