Inside

|

The problem with evil: Addressing 1971 Tazreena Sajjad "The problem is why we can or should no longer speak of evil, and why who so seem to be increasingly suspect, self-serving and irrational; why to speak of evil is in a peculiar way to perpetuate it, but at the same time, to refuse to be contaminated by the word is to perpetuate what it denotes … the repertoire of evil has never been richer, yet never have our responses been so weak."

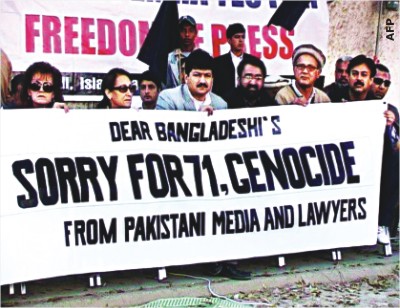

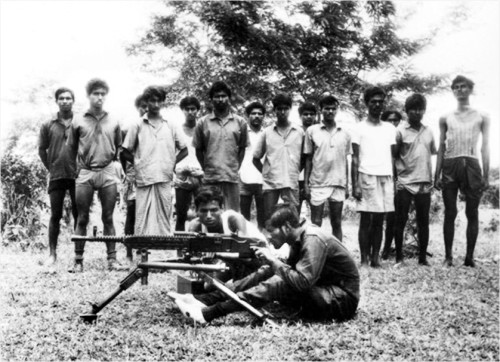

At a talk in Washington D.C. in January, I heard the following: "[T]here is talk in Bangladesh right now of trying the war criminals, you know, those who sided with Pakistan, having these tribunals, but I personally think it's not the time for Bangladesh to come up with policies that divide the people. It's more a time to improve our democracy, or to strengthen our institutions. It's not time to try people who … I mean at the time of the ci … liberation war, Bangladesh was East Pakistan before it became Bangladesh. And so we don't over here try people who supported slavery in the South. It was a civil war at that time. And so I think it's time for Bangladesh to move ahead. I think the country should focus on having elections rather than, you know, how do we beat up on our citizens." These words are neither new, nor the thoughts original. The population of every country transitioning out of war and with experience of mass atrocities comprises, roughly speaking, two camps -- those who want justice, and those who want to let bygones be bygones. I have come across similar arguments multiple times in the context of Bangladesh. They ran along the slightly (and I used the term "slightly" deliberately) similar vein of those in Pakistan who continue to define 1971 as a "civil" war, an unfortunate mistake which claimed a few thousand lives and was largely an Indian conspiracy. Before any reader takes offence, I am not suggesting that anyone with such sentiments necessarily fall in the camp of genocide deniers. But minimising the extent of the suffering of the victims -- those who died, those who survived, as well as those who resisted -- does appear to be the modus operandi of how we today deal with our own tragic history. Compartmentalise, minimize, and move on -- a convenient philosophy which greatly facilitates the focus on contemporary problems. The "peace now, justice later" echoes with the same refrain of "development now, democracy later" -- setting up both a false dichotomy and assuming these are mutually exclusive. Before analysing the problematic natures of these assertions, let me attempt to understand the logic that underscores this interpretation of our past. First, such pragmatists are present-centred -- the problems of the present take precedence over the past. Bangladesh has a host of severe challenges: poverty alleviation, economic development, women's emancipation, corruption, overpopulation, environmental degradation, health -- the list is both extensive and exhaustive. Why try to address events that happened "so long ago" when we have so much more to do in terms of the present? Second, there is an argument regarding resources -- why invest in tribunals, truth commissions, or any other form of mechanism to address crimes of the past, when the resources can better serve the population today? Third, along the same vein, the resources we do have regarding the judicial infrastructure is better put to use in addressing the crimes of today, not to prosecute crimes committed "so long ago." Fourth, there is the argument for stability -- we want peace at all costs, even if the definition of peace is based on the minimum requirement of the absence of violence. As eloquently stated by the speaker above, we do not wish to wish to "beat our own citizens on the head and divide a nation." Punitive measures will destabilise the country and create more hostilities when we can easily leave the past behind. And finally, and most controversially, there are those amongst us, who have not yet reconciled with the birth of Bangladesh and its divorce from Pakistan and who would have liked to see the entity continue as a whole. For them, a discussion of who did what to whom is at the least uncomfortable. Given both the tenacity and compelling nature of these arguments, what can someone say, sentiments aside (if that were indeed possible), about the dire need to start a war crimes tribunal? Let me begin with three general reasons why burying the past by deliberately forgetting is, simply put, not such a good idea. First, some may be able to forget; but they are never the victims or the survivors. A national policy geared on the principles of collective amnesia cannot obliterate individual memory. Second, if the government does not attend to the victims and their injuries, then it fails in one of its basic political duties -- protecting and upholding victims of injury is one of the basic raison dêtres of the state. Creating the space for survivors, liberators, victims to claim their right to remember and to ask for a national response to their trauma is within the premises of what a nation-state owes to its citizens. Bangladeshis are not unique in this demand. The state has both the responsibility to both protect and preserve. The survivors have a right to demand.

Third, grievances without redress tend to fester. Festering leads to not only hatred for the perpetrators and their descendants, but also generates an endemic mistrust of a state that has failed in its duty to vindicate the past once before, and maybe ready to tolerate injuries in the future. In the context of Bangladesh, the movement for demanding accountability not only highlights the politics of the different camps with differing opinions about 1971, but also sheds light on certain misconceptions and assertions that can be bandied around in public rhetoric. It is important to point to some of these. First of all, the demand for justice can not only be minimised by pragmatists as being practically unfeasible, but also conceptually improbable, since they can argue that it is based on naïve sentiments. In reality, the demand for a trial for war criminals is based on legal proceedings; punishment is not being sought for, and neither can it ever be handed down by a court of law for ideological differences. Particularly, conflation of the terms "supporters of Pakistan" and "war criminals" is highly dangerous and misleading. Siding with Pakistan, or supporting the unity of Pakistan, although distasteful for many, is not a crime in legal terms; participation in the destruction of human lives and property is. The demand for trial is for those who directly or indirectly participated (organised, orchestrated, mobilised) in the killing, raping, torturing of civilians in the course of the war. Punishment is being sought for real crimes, not for political opinions. To distill this in layman's terms, the arms of law cannot punish an individual for thinking of a criminal act, but only for executing it. Furthermore, those who argue that any form of justice is unnecessary for 1971 basically suggest that a murderer who lives in your own neighbourhood, and has murdered your family member, ought not be tried because it will disturb the peace of the neighbourhood. Surely, even such a crude example captures the absurdity of the understanding of peace at all costs.

Second, what needs to be clarified perhaps is the demand for war crimes is a move towards a systematic appeal to address the issue of accountability. A focus on trials, whether effective or not, or whether they will come to pass or not, is secondary to a more critical issue. The desire amongst those demanding trials is for justice, not vengeance. This should be a move forward through an organised, highly transparent procedure, led by the state, through functional legal and hence legitimate mechanisms whether effective or not, or whether they will come to pass or not, is secondary to a more critical issue. The desire amongst those demanding trials is for justice, not vengeance. This should be a move forward through an organised, highly transparent procedure, led by the state, through functional legal and hence legitimate mechanisms and far removed from narrow political interests and motivations of individuals or groups. Third, the desire is for identifying individuals, not groups or political parties as a whole for crimes they committed in 1971. Being able to separate group identities and focusing on individuals for their role in causing suffering goes a long way to establishing individual culpability and exonerating those who have had to shoulder the stigma of being associated with collaborators. Fourth, there needs to be recognition that such a process will never be clean and easy. Serving justice is a messy business, and when it involves war crimes and crimes against humanity, the reality is messier. There is no pretty picture to paint for this reality. If the reliance is on punitive measures, and barring any possibility of a truth and reconciliation commission, then the country has to live with the "not guilty" verdict while it celebrates guilty verdicts. And finally, because these individuals who did not believe in Bangladesh are still citizens of the country, they deserve a fair trial, regardless of whether we can truly grasp the ramifications of such decisions. It is also important to note that those who suffered the least, are the most willing to forgive and forget, and some of those who have suffered the most, still hold out for some hope of justice. From a bird's eye view, the quiet resignation of many have implied that in general we had reconciled with our horrific past. I question this. With blanket amnesties provided for political reasons after the war, and incorporating purported war criminals into the political process, there has been little scope to discuss the issue of accountability and little hope that demands for justice will ever be heard.

Resignation, as has happened in many countries, has been mistaken for reconciliation. In turn, for thirty seven years, the state and those who are wary of the tribunals have basically asked rape victims, torture survivors, orphans, persecuted religious minorities, eyewitnesses, and those who have lost homes, families, identities to live side by side by those who have betrayed them as a demonstration that we as a nation have reconciled, and are ready to move on. May it be contemplated that we have punished our own, by making them relive the horrors of their experiences for 13,505 days and counting. 1971, a poor man's war, continues to be largely a poor man's burden. Finally, the pragmatists' focus on the present is interesting because it Forgive, forget, move on and reconcile within our own selves, the horrors we witnessed and the scars we bear, not just as survivors, but as a nation, that has been systematically denied its right to a continued, comprehensive history of its emancipation. Implicit in this call to forget, is the message that it is not yet time. Perhaps, according to some camps, a transitional society, with a weak, non-existent rule of law and a host of post conflict reconstruction challenges can offer this argument (although in some cases as in Rwanda, Bosnia, East Timor, Uganda, Liberia and Sierra Leone, the need to address justice has gone hand in hand with the necessity to deliver peace).

The question is, does this message apply to Bangladesh? Has this period of waiting -- thirty seven years of waiting with hope and resigning with despair -- been a sufficient period of time to hold out for demands for accountability? How much longer should a nation have to wait for deliverance, or at least an acknowledgement of their demands? Can the pragmatist look survivors in the eye and tell them what they mean by the "right" time and when it will come? Is there ever a good time, a right time, to prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity and crimes of genocide? Does waiting, and biding for the ideal moment to try systematic rape, torture, destruction of villages, slaughtering of civilians, massacre of intellectuals, forcing women to have children born of sexual violence, make the issue of seeking justice any easier? Waiting for the right moment can perhaps only mean one substantive reality -- the loss of more eyewitnesses, the loss of momentum in creating documentation for trials and truth commissions, and a continued fostering of a sense of resignation of survivors that the state will never hear their voices, because they were never important. Tazreena Sajjad worked in transitional justice and the rule of law in Afghanistan and is a member of the Drishtipat Writers' Collective. |