Inside

|

The Rights of the Rohingyas Ziaur Rahman and Mahbubul Haque urge more be done to help these refugees Any student of economics would quickly relate to the theory of scarcity, which starts with the premise that "the world will always be scarce in resources." There is no better way to reaffirm this theory than by looking at the global food and environmental crisis that is precariously pushing a large majority of people into extreme poverty. With significant climatological changes, bad harvests, and managerial inefficiency, many countries of the world are seeing their agricultural resources being depleted. These issues lead us to discuss matters of poverty, and the rights of the extremely marginalised. From a rational point of view, when a country suffers from a debilitating economic crisis, issues of ethics and morality are often trampled upon; however, at this juncture, as a nation, we need to revisit our vision of building an equity-driven, fair, and accountable environment for people of all colours and creeds. Bangladesh is home to about 45 indigenous communities, which make up a small but notable part of the population. In addition to our own indigenous (Adivasi) community, we have perhaps as many as 100,000 Rohingyas (30,000 as official count) who are considered stateless, which is an affront to civilised society by any count.

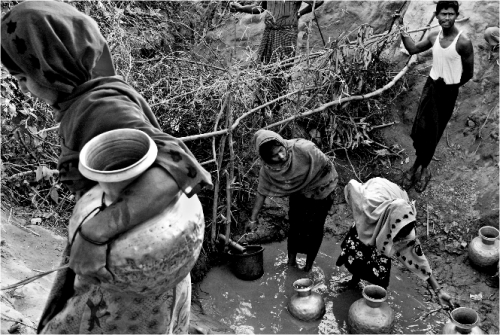

On September 13 last year, the United Nations adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of the Indigenous People, which marks the achievements of countless indigenous peoples and the organisations that have campaigned with them to establish these rights. Unfortunately, Bangladesh was among the eleven countries that failed to sign, on the pretext of not being properly clear on the definition of "indigenous" or "Adivasi." Being ethically sensitive citizens of Bangladesh, we believe this was counter-productive, especially when Bangladesh wants to brand itself as a nation of multi-party pluralist democracy where freedom of thought, speech, and association will unquestionably be availed. Now, let us draw attention to the culturally sensitive issue of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Rohingyas have their origins in Burma (now Myanmar). This ethnic community has been existing in a state of national limbo and has been severely affected by the abuses of the Burmese regime. Denied Burmese nationality, they are hemmed in within the areas of the country in which they live. Therein, they face tyranny against their rights to move freely within the country, and discrimination is rampant on account of their religion (the Rohingyas are Muslims in a Buddhist majority country) and ethnicity. In order to break loose from this long-standing oppression of the junta, many Rohingyas have fled as refugees into neighbouring countries. Due to geographic proximity, many Rohingyas living along the border of Burma and Bangladesh have entered Bangladesh. In addition, being more ethnically and linguistically related to the Bengali people of Bangladesh, the group was further motivated to seek refuge in Bangladesh as opposed to India, Thailand, and other regional countries, a point that the ruling junta seeks to exploit by emphasising the links between the Rohingyas and the Bengalis. The status of the Rohingyas in Bangladesh is, however, precarious. Living in non-sanitary and inhuman conditions in refugee camps not exceeding half a square kilometre, they have not been accorded any official status. The children and adults are mostly devoid of formal schooling, and thinking about Millennium Development Goals for their uplift feels like a dream. The Bangladeshi government considers them to be Burmese and pushes them back to Burma, from where they have been forced out because they are seen as Bengalis. The end result is that these people have no nationality, and no state protects them nor provides them services and rights. This political volleying is enfeebling their already desperate economic condition, turning them into "political prisoners" and "climate prisoners" as their movements are severely restricted and they are thus virtually unable to work in a free franchise and be economically productive. The system is making them completely dependent and, ironically, forcing them away from economic emancipation. In light of the events in Burma during September and October 2007, the uncertainty about the future actions of the regime, and the wider global politics of Islam and of human rights, the Rohingya issue is significantly neglected in relation to its importance for the region and for the Rohingyas, who have been subjected to decades of human rights abuse, and stand as a nationless, stateless people with no means of representation. While we, the Bengali-speaking community, are beating the drum for freedom to speak and freedom of rights, the duality of our behaviour is revealed when we accord next to no freedom for these Rohinghyas. It is a pressing moral prerogative for Bangladesh to introduce the Rohingyas into our society, whilst also promoting the human rights of the Rohingyas in Burma and advocating to all nations of the world to give credence to their rights to citizenship in the countries in which they are currently domiciled. Who are the Rohingyas? The strife of the Rohingyas can be followed back to particularities of the Burmese laws on nationality. "Approximately one-third of the population is made up of seven ethnic minorities who live in seven ethnic minority states. The state of Rakhine (historically known as Arakan) in Western Burma is where most of the Rohingyas live, a geographically isolated state characterised by coastal plains, rivers, and mountains (Amnesty International, 2004)." Most of the 700,000 to 1.5 million Muslims in the state are Rohingyas.

The Burmese military government, known as the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), which has been in power since 1968, recognises 135 national races in Burma through its 1982 Burma Citizenship Law. This creates three classes of citizens, known as full citizens, associate citizens, and naturalised citizens (Amnesty International, 2004). The rights that associate and naturalised citizens may or may not enjoy are determined by the "Central Body," also created by the 1982 Law, which Amnesty reports has "wide ranging powers." The Rohingyas are not considered to be one of the 135 national ethnic groups, and so are not entitled to be full citizens. To qualify for associate citizenship, an individual must be eligible under the preceding 1948 Citizenship Act, and have applied for citizenship under that. Few Rohingyas are in this position. For naturalised citizenship, one must be in possession of documentary evidence of residence in Burma prior to independence on January 4, 1948. Birth lists do not show place of birth, and, consequently, the Rohingyas cannot usually produce the evidence required. In legal terms, the Rohingyas do not have Burmese nationality and do not have ethnic nationality status. The SPDC does not accept the existence of an ethnic group known as Rohingya. History is fraught with grave injustices, and the history of the Rohingyas is strewn with monumental and deliberate fabrications, causing them institutionalised mistreatment. It is assumed that Muslims arrived in Burma as a consequence of the Anglo-Burmese wars of the early 19th century, launched from British-controlled India.

History's brutal pages did not allow them to live in peace. Many Rohingyas were forcibly evicted, or willingly chose to leave, during the oppressive regime of the Burmese King Bodawpaya after his 1784 conquest of the Rakhine kingdom. They settled around the vicinity of Chittagong. The British allowed resettlement of these displaced people after the defeat of this regime. It is this return that is often distorted to be seen as a first arrival of Rohingyas by the Burmese government and those who deny the Rohingyas citizenship, and is, unfortunately, accepted even by Amnesty International (2004). History is always written by the victors, and is unkind to the vanquished. In this case, the Rohingyas were the vanquished and settled for a history that only time can change to its true turn of events. Rohingya culture and society In addition to Bengali influences, there are Urdu, Hindi, and Arabic words, reflecting the Indian and Muslim tradition of the group, and also Bama and English words as a result of the British colonial occupation and the interaction with Burmese majority groups. Unlike the majority of the Burmese population, they are Muslims. Mosques and religious schools are ubiquitous in the region, and women often wear the hijab. Treatment of Rohingyas in Burma Forced labour remains a major concern of human rights groups among Rohingyas. Burma is known to use forced labour widely, especially from ethnic minority groups. Although it is a signatory to the Convention on Forced or Compulsory Labour, Burma has been known to practice forced labour in spite of it being made illegal as per ILO conventions. However, whilst the ILO has concluded that the numbers employed in forced labour has in general fallen across the country, there has been little change in the Rakhine state. The confiscation of land is also a major concern for human rights groups. The SPDC has a policy of relocating non-Rakhine people to the region in new "model villages," which are often populated by the NaSaKa and their families, former insurgents, plains people and non-Rohingyas from the state. This sorry state of affairs mirrors the scenario where the government of Bangladesh had relocated Bengalis to the CHT regions over the last few decades without understanding the harmony that needed to be blended between the indigenous community people and the Bengali people, causing tensions and brewing distrust among different communities. In conclusion, the time has come to allow the Rohingyas to live their lives with the proper dignity of human beings. As a progressive majority-Muslim state, Bangladesh needs to show resolve by coming full circle and give serious thought to the full assimilation of the Rohingyas as Bangladeshi citizens while allowing them complete and unequivocal rights to associate and speak their own mother tongue and offering them freedom to own property. Let us also raise global consciousness at the civil and national levels so that other countries also offer Rohingyas citizenship in their respective countries; and most importantly, unequivocally denounce all harassment of Rohingyas in Burma and any other part of the world. Ziaur Rahman is CEO, IITM, and Mahbubul Haque is Director, Neeti Gobeshona Kendra. Photo: MAHBUB ALAM KHAN/ DRIKNEWS.

|

The annexation by Britain in 1824 is, therefore, seen by many elements as the dividing line between "indigenous" pre-colonial peoples and the arrival of Bengali Muslims and Hindus from India as the new territory was incorporated into the growing empire. While others were settlers, the Rohingyas were "beyond any shadow of doubt, indigenous people of Arakan. They did not settle during the British occupation of Arakan (post-1824)," writes expert Habib Siddiqui.

The annexation by Britain in 1824 is, therefore, seen by many elements as the dividing line between "indigenous" pre-colonial peoples and the arrival of Bengali Muslims and Hindus from India as the new territory was incorporated into the growing empire. While others were settlers, the Rohingyas were "beyond any shadow of doubt, indigenous people of Arakan. They did not settle during the British occupation of Arakan (post-1824)," writes expert Habib Siddiqui.