Inside

|

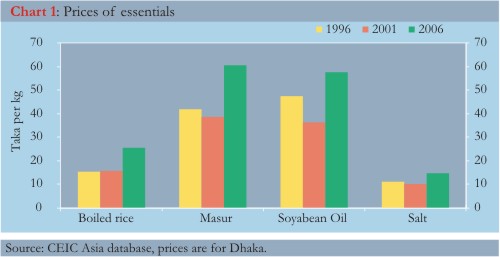

Food Prices and Food Security Jyoti Rahman “We will have to … reduce price hike and improve people's living standard," said the prime minister at her first news conference after the landslide election victory. Since then, she and her senior ministers have repeatedly stressed that bringing down the prices of essentials within people's purchasing power is a priority task for the government. This is not surprising given the importance most voters accorded to high prices in the lead up to the election.1 The Awami League capitalised on voters' concerns by pointing to its better record on this issue. Prices of essentials -- the proverbial rice, lentil, cooking oil and salt -- either remained virtually unchanged or fell between 1996 and 2001, while all prices rose under its rival (Chart 1). To put the price rises in context, a male farm labourer earned an average daily wage of 48 taka in 1996 (with which he could buy 3.1 kg of rice), 67 taka in 2001 (buying 4.3 kg of rice) and 95 taka in 2006 (buying 3.7 kg of rice).

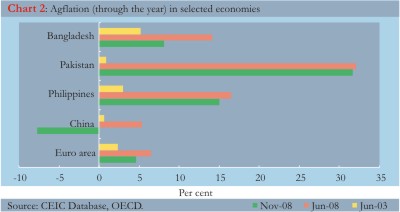

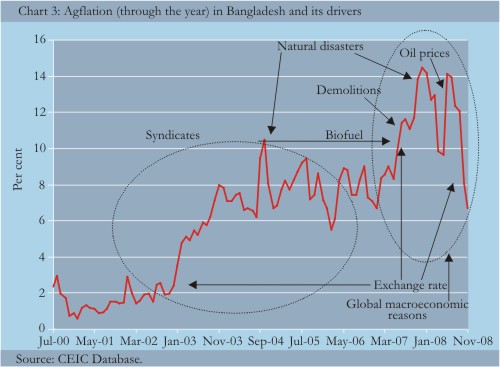

It is no surprise, then, that the voters have overwhelmingly turned to AL for lower prices. But will AL be able to bring prices down, or at least stem the rate at which prices have been rising? And in the longer term, what does the government need to do to achieve food security -- defined by the Nobel laureate Amartya Sen as access to food products, particularly by poor people.2 There are grounds for optimism as far as the near term outlook for agflation -- food price inflation -- is concerned. But drivers of agflation and food security are complex and multifaceted. This piece stresses that for food prices to stabilise, if not fall, and for us to achieve food security over the medium term, a lot more than "cracking down unscrupulous business syndicates" will be needed.3 What has been driving agflation in Bangladesh? As agflation is a global phenomenon, it follows that it has global drivers. One major driver has been the sustained rise in the pace of economic growth in large emerging economies over the past decade. This resulted in material improvements in the living standard of tens of millions of people. As people became more prosperous, their diet changed towards more poultry and meat, raising the price of those products. Of course, livestock has to be fed too, and as farmers switched to producing grains for the animals, prices of all grains rose. In addition, increasing demand from the energy-starved emerging economies such as China is a major reason why energy prices shot to record levels by mid-2008. And higher energy prices translated into higher prices of farm output through increased fertiliser and transportation costs. The increasing prosperity in the emerging economies is a gradual process, whereas agflation sharply increased around the world in 2007 and into 2008. Much of the rise in the global agflation in 2007 was a result of strong demand for subsidised corn-based ethanol as a fuel for cars.4

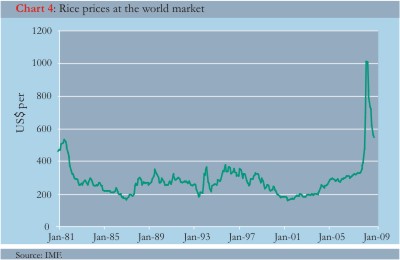

As oil prices rose sharply in recent years, the search for alternative fuels became a policy priority. American policymakers' alternative fuel of choice has been ethanol, whose production is subsidised by legislation. The artificial expansion of ethanol production created an increase in the demand for its main input corn, driving up its price. American farmers reacted by diverting productions away from other crop, raising their prices as well. Over half of the world's unmet need for cereals in 2007 could be accounted for by the American ethanol programme. By early 2008, various governments faced political heat from agflation, and one way they tried to tackle it was through restricting food exports. Ironically, these export bans then led to a shortage of food products available in the global market, raising their prices again. Indeed, export restrictions played a large role in the dramatic rise in rice prices in late 2007 and early 2008. The initial acceleration in rice prices began when India, the world's second largest rice exporter, imposed export restrictions on rice. Similar restrictions were then imposed by Vietnam, China, Cambodia, Indonesia, and Egypt. This in turn, sparked fears among importers, such as the Philippines, over the reliability of their suppliers, causing countries to increase stockpiles. As a consequence, rice prices rose rapidly, reaching over $1,000 a ton in April 2008. In Bangladesh, agflation started rising in 2003, much earlier than the rest of the world, suggesting that in addition to the global reasons, local factors were at play. The most important domestic shocks to food prices have been natural disasters -- floods of 2004 and 2007 and Cyclone Sidr. While natural disasters result in sharp rise in price levels, absent other reasons, as the crop production recovers, prices tend to return to their previous levels. For example, this was the case in the aftermath of the 1998 flood. But prices did not fall after recoveries from disasters in recent years. In addition to the natural disasters, two other factors have affected our domestic agriculture markets in recent years. Much has been made of the collusive behaviour of business syndicates and hoarders under the last elected government. In the early months of the caretaker regime, demolitions of local bazaars under the auspices of anti-corruption drive also pushed up food prices, particularly damaging the food security of the poor. While both syndicates and demolitions would have raised prices to levels higher than would have been the case otherwise, absent some other mechanism, it is hard to see why they would have resulted in continuously increasing agflation, as has been the case in Bangladesh for the past half decade. One such mechanism is the taka-rupee exchange rate.5 One Indian rupee cost 1.20 taka in late 2002. Taka depreciated to about 1.50 taka per rupee by early 2005. As the taka started depreciating in 2003 and 2004, Indian imports -- including food imports -- became more expensive in Bangladesh. In 2007, taka depreciated again, to be near 1.75 taka per rupee by early 2008. This set off another spike in imported food prices above and beyond the price rises in the Indian market. Underlying all these is the role market expectations play. Various participants in the market -- distributors, wholesalers, retailers -- expect prices to rise, and they try to increase their stock as much as possible before higher prices set in. Of course, this behaviour itself raises price. After skyrocketing earlier in the year, agflation abated across the world towards the end of 2008. As the global financial crisis hit and the world economy entered what is being feared as the worst recession since the 1930s, commodity prices tumbled globally. Meanwhile, taka appreciated to about 1.40 taka per rupee by the end of the year. And our farmers harvested back to back bumper crops throughout the year. What is needed for food security? Government policies have important roles to play when it comes to food prices, or more broadly food security. Governments typically rely on a number of measures to ensure food security when faced with adverse shocks. Some of these measures are, however, better than others. Governments try to directly lower food prices through price controls, or indirectly try to affect retail prices through export taxes or reduction of import tariffs. Price controls are typically difficult to administer, and usually lead to black markets and breed corruption. Taxes or subsidies, on the other hand, are easier to administer. That's why many developing countries resorted to these methods when agflation rose in late 2007. But such government interventions have unintended consequences. As we saw in early 2008, attempts to reduce prices by stopping exports led to an increase in rice prices in the global market. Even for food surplus countries, export restriction that lowers the domestic price can result in lower production and increased demand at a time of shortage, hurting poor farmers at the expense of urban consumers who may be far above the poverty line.

To the extent that Bangladesh is -- and given our extremely high population density, will likely to remain -- a net importer of food products, liberalisation of trade in food products benefits us. This is not to say that we should forget about increasing farm productivity or stop investing in agriculture. Of course we should seek to boost our own agricultural output. But there are limits to how much we can produce, and regardless of our output, trade in agriculture benefits us. Ensuring a functioning global market in food products should be a priority in our foreign policy. While global liberalisation of agriculture trade may be a long drawn task, our government can engage in two specific initiatives. Bangladesh should lead a global campaign against the damages wrought by inefficient subsidies to the bio-fuel industry. In this, the government can enlist the help of activists at home abroad. Plus, Bangladesh should explore an Asian agreement on rice trade that stops counterproductive export bans. In 2007, nearly three-quarters of global rice exports came from Thailand, India, Vietnam, China, and Pakistan. We have friendly relations with all these countries. An Asian Rice Trade Agreement should therefore be an achievable objective. In the meantime, the unfortunate reality is that the global food market is likely to be beset by government interventions, self-defeating or otherwise, in the medium term. Given this, what else can the government do to ensure food security? The government can try social-safety-net approaches such as cash transfer, food for work, food ration/stamp, school meals for the poor. This can, in principle, be targeted to those most in need. Further, safety nets can help whether or not the problem arises from domestic or international causes. Of course such safety nets cost money, and in the context of a large budget deficit, these safety nets would have to come at the expense of other tasks.

Another approach would be to use public stockpiles. This however requires a well-oiled administrative mechanism. For example, the government would need to know about the quantity of stocks required and the amount to release at any stage. Importantly, food stocks in the granary are not by themselves enough to ensure food security -- the key is ensuring that poor people have access to food. As it happens, the previous AL government, building on the work of its predecessors going back to the late 1970s, did successfully use both social safety nets and public stockpiles to reduce food prices after the devastating flood of 1998. Like much else, these programs suffered under the last elected government (with tacit donor encouragement), and restoring them to working condition should be a priority for the new government. What about the syndicates? Measures will be taken to reduce the unbearable burden of price hike and keep it in tune with the purchasing power of the people. After giving the highest priority to the production of domestic commodities, arrangements will be made for timely import to ensure food security. A multi-prong drive will be made to control prices along with monitoring the market. Hoarding and profiteering syndicates will be eliminated. Extortion will be stopped. An institution for commodity price control and consumer protection will be set up. Above all, price reduction and stability will be achieved by bringing equilibrium between demand and supply of commodities. The manifesto appears to put a lot of emphasis on price control and busting of syndicates. This may well be a popular political rhetoric, but unless implemented in a well thought out manner, syndicate busting or other law-and-order approach to food security will likely to prove counterproductive. After all, the caretaker regime's attempts at similar approaches as part of its much-touted anti-corruption drive did end in higher agflation. This does not mean that there is no need to worry about "unscrupulous businessmen." There is. Adam Smith, the founder of market economics, noted this over two centuries ago. People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices. … though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary.6 There is a clear need in Bangladesh for a government agency to regulate the supply side of the market in the form of competition policy that ensures new businesses can enter the market, and demand?side interventions, in the form of consumer policy, that protects the consumer from substandard products and services. This is an important task. And the government should establish such an agency.

However, it is important to realise that this agency, by itself, won't reduce prices of essentials to the purchasing power of individuals if other factors are ignored. Food security is a complex, multifaceted issue. "It is all due to syndicates (or foreigners, or some other villain)" may be politically popular rhetoric. But with the election behind us, it is time to deliver, and one hopes that the government will take "multi-pronged" actions to honour its promise. 1. According to a Daily Star/AC Nielsen poll, for example, 41 per cent of those surveyed noted high prices as an important issue facing the incoming government. For details, see here: http://www.thedailystar.net/ suppliments/2008/opinion%20poll/o_poll.htm. 2. Sen, Amartya, 1981, Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. 3. The newly appointed finance minister talked at length about price control and syndicates in his first meeting with journalists after taking office. 4. See Rahman, J., Of food and fuel, Forum, February 2008. Photo: AFP Jyoti Rahman is an applied macroeconomist. |