Inside

|

The Future of Foreign Aid Fahmida Khatun The development of Bangladesh is still characterised by two parallel trends. The first is the mobilisaiton of concessional foreign aid, and the second is getting effective market access for exports from Bangladesh. Though the share of foreign aid in GDP has been halved during 1991-2007, the role of aid in dealing with critical issues, some of which are laid down in the MDGs, cannot be undermined. There is a need for adequate investment fund to implement the PRSP.

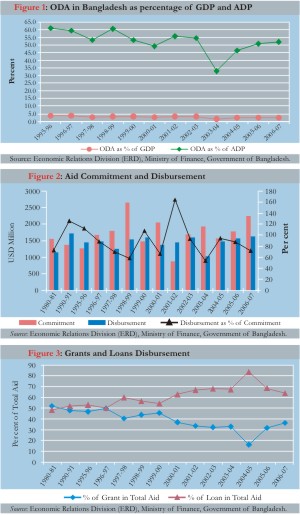

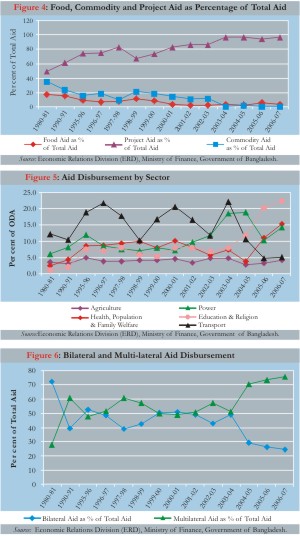

While the MDGs are halfway through the targeted fifteen years for achieving goals several areas are still lagging behind, with the likelihood that those targets may not be reached by 2015 without a big push in terms of both implementation and increased investment. Moreover, the threat of climate change, food crisis, fuel shortage and financial crisis may have an impact on the progress of MDGs and implementation of PRSP. Hence, aid as a source of financing for reaching the MDGs is still an important component of required resources. However, unless this aid can be made more effective, the objective of reducing poverty may remain a far-fetched goal. Increased effectiveness is particularly important in view of the fact that the demand for resources is on the rise, with an increasing number of countries facing conflicts. In addition to traditional recipients, the demand is increasing in conflict and post-conflict countries. Much of this aid is also used for debt cancellation in war-affected economies such as Afghanistan, Iraq, and Nicaragua. The aid scenario in Bangladesh has been undergoing changes during the last few years. The change is manifested not only in terms of sources and volume of aid, but also in terms of sectoral allocation and utilisation. A closer look at some of the macroeconomic aspects of aid to the Bangladesh economy reveals some of the changing trends. Coming out of aid dependency: During the last one and a half decades (1991-2007), Bangladesh has increasingly become integrated into the global economy. In 1991, less than a quarter of the Bangladesh economy was associated with the global economy, in 2007, the comparable figure is about 56 percent, implying that Bangladesh has gradually become a trade dependent economy from an aid dependent one. Foreign aid and exports were almost equal in 1991, but foreign aid flow was a little above 13 percent in 2007. Import coverage during this period has increased by 1.5 times while import coverage by merchandise and services export has increased from less than 75 percent to more than 100 percent. Share in the economy: Though ODA disbursement showed some volatility over the years (1996-2007) the share in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has remained constant at around 2.5 percent during the recent past. When compared with the Annual Development Program (ADP) the share of ODA is around 51 percent at present (Figure 1). Discrepancy between committed and disbursed ODA has always persisted as a significant amount remains in the pipeline. Except for a few exceptional years, the disbursement was much lower than commitment (Figure 2). Composition and sectoral allocation: The share of grants in total foreign aid is declining, from 46.9 percent in 1996 to 36.2 percent in 2007, while the share of loan increased from 53 percent in 1996 to 63.8 percent in 2007 (Figure 3). In spite of reduced dependency on foreign aid there is a need for ODA in development projects. Currently, more than 96 percent of aid comes as project aid, and the rest 3.7 percent as food aid (Figure 4). The contribution of ODA is still significant for critical sectors such as health, education and physical infrastructure (Figure 5). However, allocation for education and health is higher than for infras-tructure (power), which needs massive investment. Globally, the sectoral allocation of aid within coun-tries has shifted towards the social sectors from the productive sectors. There has been a significant increase in aid for the health and education sectors, with particular emphasis on HIV/AIDS and basic education in the poor countries of Africa and Asia. Agriculture and industry have experienced lesser allocation. Allocation for infrastructure has started to increase recently. While increased allocation for social sectors is important for increasing productivity (healthy and educated people can contribute more to the national production) and achieving MDGs, a decline in the productive sector will also have serious implications on the poverty reduction initiatives as there is direct linkage between poverty reduction and performance of productive sectors. These sectors not only contribute to the GDP of countries, but are also sources of employment and income for the vast majority in the developing countries. Investment in infrastructure improves connectivity, which has a direct positive bearing on productivity. Also, the needs and local conditions have to be the major criteria for aid allocation if the fight against poverty is taken seriously. The sectoral bias is a donor driven phenomenon resulting from a shift in emphasis at the headquarters level. It is not necessarily a response to the recipients' requirements, and individual donor decisions tend not to take account of the decisions of other donors, hence leading to the over-emphasis on certain sectors. This goes against the ownership and alignment principles of the Paris Declaration on aid effectiveness, which refers to giving priority to the needs of the recipient countries. Bilateral versus multi-lateral: At the global level currently, bilateral aid agencies contribute about 70 percent of total aid and multi-lateral agencies contribute the remaining 30 percent, indicating a clear preference of donors to channel their development assistance through bilateral rather than multi-lateral agencies. As opposed to the global trend, multilateral aid comprises the lion's share in the aid basket. Though the shares of bilateral and multi-lateral aid were close to each other during 1999-2004, the share of multi-lateral aid started to increase since 2005 (Figure 6). This is a positive feature of aid disbursement in Bangladesh as global experience shows that, for most bilateral donors, poverty and development are not the primary determinants for how aid is allocated although concerns about these issues make up the debate about aid. Rather, a whole raft of political and strategic objectives, combined with developmental objectives, drive bilateral donor allocation decisions, both between and within countries. One way to solve this problem would be to disburse a greater proportion of resources through the multi-lateral system. This brings the added advantage that there is also a scope for involvement of the recipient countries in the decision-making of the multi-lateral organisations.

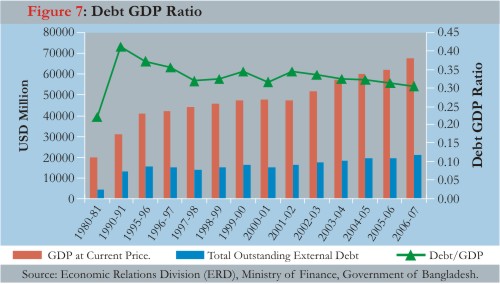

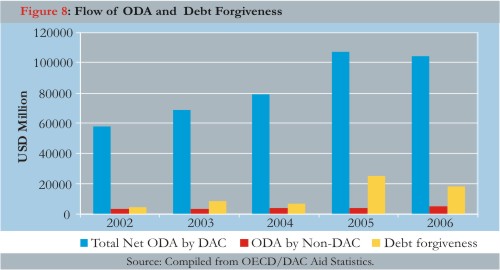

However, given the concerns about the dominance of the governance of the Breton- Woods institutions by rich countries, and the well-known failings of the UN system, multi-lateralisation of aid is in fact contentious. The experience of Bangladesh is one where the dominance of such multilaterals has been widespread, and pre-occupied with the state of governance and the nature of politics, which was far from welcome by the policy makers. Format of delivery: The global aid regime has also experienced a marked rise towards program-based approach from project-based approach. However, the OECD/DAC's baseline monitoring survey in 2008 shows that only 25 percent of the aid is program- based in Bangladesh (Table 2 in Section 3). While program-based aid is preferred to the project-based one, one important concern as regards the increase of program-based support is that it may undermine the importance of allocation for some important project type interventions. Debt obligation: The debt obligation per capita was $144 in 2007 compared to per capita ODA of $11.3. The debt-GDP ratio has been around 0.31 since 1998 (Figure 7). Though there has been huge debt relief in countries with social, natural and political problems, Bangladesh has not benefited from such programs (Figure 8). Increased aid to Afghanistan and Iraq, debt relief for Iraq and Nigeria, emergency assistance to countries hit by tsunamis do actually imply that fewer resources are available for poverty reduction and achievement of the MDGs in other countries. How aid can be made effective There have been opposing views as regards the necessary conditions in recipient countries for aid to be effective. Some suggested that good economic policy is a pre-requisite for the effectiveness of aid. This view has been challenged by many who find that aid is effective even independent of policy. Admittedly, the poorest countries are also those with the least capacity administratively, institutionally and in terms of policy making. This overall capacity deficit imposes a major constraint on their policy making and implementation ability, including the areas of aid negotiation, management and utilisation. However, correlating aid effectiveness with policy efficiency ignores several other factors characterising the failing aid system and puts the burden of responsibilities solely on the recipient country. As a result, issues such as revealed allocation priorities of the donors, mismatch between aid flow and national needs, predictability of flow, lack of balanced mutual accountability, and trends in global aid regime do not get necessary attention.

That not only the policies of the recipient countries but also the way aid is prioritised, channelled and processed are the main reasons for ineffective aid has been recognised in the Paris Declaration for the first time. Efforts to reach a consensus on how the issue of aid effectiveness can be pursued had started even earlier at several forums. The Monterrey Consensus (2002) emphasised that enhanced aid flows must be accompanied by efforts to improve aid effectiveness. The High Level Forum (HLF) in Rome (2003) was another step forward in drawing more attention to the issue. With the signing of the Paris Declaration in 2005, the issue of aid effectiveness has gained further prominence. The Paris Declaration is a commitment of the international community to key principles for aid reform. It was signed by over one hundred ministers, heads of agencies and other senior officials. It establishes global commitments for donor and partner countries to support more results-based aid in the context of scaling up, untying and monitoring a set of indicators. Countries and organisations have committed to continue to increase progress in the five pillars -- ownership, alignment, harmonisation, management -- for results and mutual accountability as set out in the Paris Declaration. The other milestones for evaluation and advancement of the agenda for aid effectiveness was the Accra High Level Forum 3 (HLF3) in September 2008 and Conference on Financing for Development in Doha in November 2008, where stakeholders within the aid relationship attempted to achieve a broader consensus through taking stock of the state of delivery of the Paris Declaration.

Aid effectiveness in Bangladesh First, capacity has been a major constraint. Traditionally, the donor-recipient relationship has been an asymmetric one involving a strong and a weak party, where political and economic structures of domination and exploitation provided little space for the latter to choose.

Furthermore, over the years the aid system has gone through various reforms, but with few inputs from recipients. Consequently, marginal participation of aid recipient governments in the global debate on international aid system has been a limiting factor towards effective reforms of the overall architecture. This has been partly due to low enthusiasm on the part of the donors to encourage recipient countries to be involved in the processes of the global aid system. The recipient countries remained largely engaged in debates at national level on the nature of impact. As some developing countries started to achieve success in boosting their merchandise and services exports, their enthusiasm regarding foreign aid has also dampened. However, it is also true that even when there was awareness of the national relevance of the global aid system, recipient countries faced serious capacity deficit in articulating their views. But capacity is not just lacking on the partner side, donors too lack capacity to implement their commitments. The monitoring process requires considerable capacity of both donors and partners as a result of the high transaction costs. Donors are not moving fast towards aligning more generally with country systems. There is a disconnect between headquarter rhetoric and policies and actions on the ground. Second, the level of participation of civil society in the global aid debate has been traditionally very low. Such participation should also be ensured at the national levels by the partner countries. Although the involvement of national governments is critical, this must be broadened out to include civil society, which is in many ways a real ally on a number of key issues within the discussions.

Third, aid effectiveness is not isolated from development effectiveness. In addition to improved capacity and inclusion of all stakeholders a good deal of political interests and commitment at the highest level is also required in order to achieve the goal of aid effectiveness. However, the ultimate aim must be development effectiveness, and this must be seen in broader terms, emphasising social justice and not just growth. Dr. Fahmida Khatun is an Economist at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). |

|||