Inside

Original Forum Editorial |

| What Works for the Extreme Poor in Bangladesh? --Roland Hodson and Azim Manji |

| An Extreme Poverty Manifesto-Joe Devine |

| Making the Invisible Visible --Sanjan Haque |

Working for the Devil? --Iresh Faruk

|

| Photo Feature: Black Water --Thomas Lekfeldt / Moment Agency |

| The Man with a Plan-- Adam Panetta |

| Understanding Multiple Realities in Bangladesh: A Play in 4 Acts-- Tom Zizys |

| Baader-Meinhof to Bin Laden--Nadeem Rahman |

| Justice Now-- Tazreena Sajjad |

| Catalysis for a New Dhaka --Kazi Khaleed Ashraf |

| The Green Passport --Zakir Kibria |

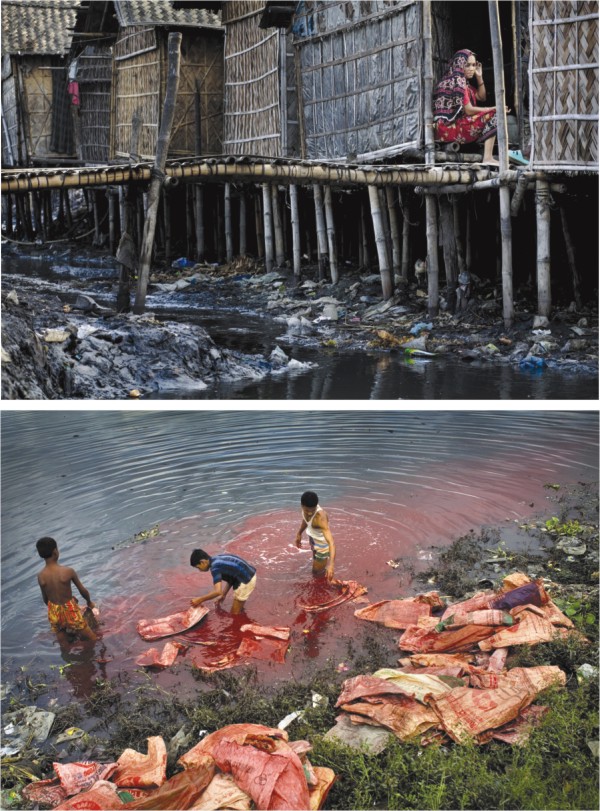

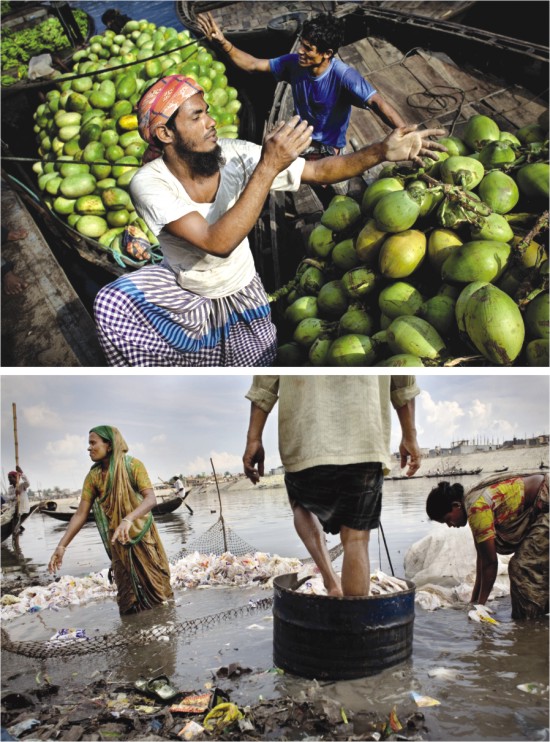

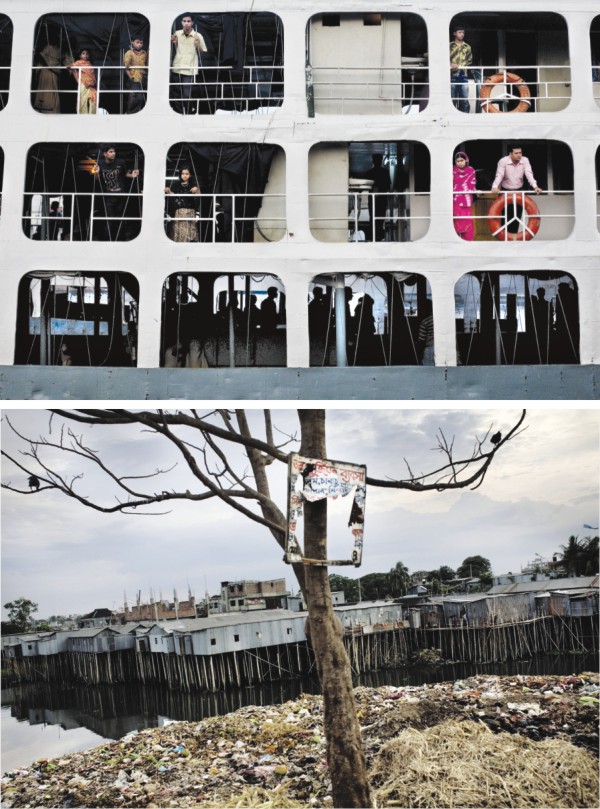

Photo Feature Black Water A photo feature by Thomas Lekfeldt / Moment Agency

The Buriganga River has for centuries been the lifeline of Dhaka. Everywhere you see small worn-out wooden boats that are rowed by weather-beaten men. They zigzag across the river as they fight an eternal battle to avoid freight ships, shuttles and ferries. Along the banks of the river people bathe, wash their clothes and unload goods from rusty ships. Innumerous crows in search for eatable leftovers fly along the pale black water of the river. It smells of sewage, of chemicals and of the garbage and untreated waste water that is poured into the river from industries and sewers. But far from everyone notices the dangers of the polluted black water. A 31 year old rickshaw driver is baths under the Babubazar Bridge every morning and evening. He has done this ever since he was a little boy. He does not think there is anything wrong with the river. “The water makes us strong,” he says before he dives below the surface to wash away the dust of the city from his body. This hardly sounds probable. But there have been no specific investigations into the effects of using the polluted water for bathing, washing clothes and other purposes. Some of the bathers at the Babubazar Bridge do complain of itching skin, eye problems and discomfort by bathing in the river. But they explain that they do not have anywhere else to go. They are poor - and without alternatives. The main part of the pollution comes from waste water from the many tanneries that are located in the Hazaribagh area of Dhaka. Every day at least 50,000 tons of untreated waste water run into the river from the industries in the area, mainly from the tanneries. Emdad Hossein grew up in Dhaka but now he lives in southern Bangladesh and often he comes to Dhaka on the ferry. Every time he arrives in the capital he is confronted with the worsened condition of the river. He tells that in the end of the 1970's he often swam across the river with his friends. The river had at that time already begun to show signs of pollution but it was not nearly as bad as it is now. Back then the river was not black and the water did not smell the way it does now. Often fishermen were sailing out on the river in the mornings to catch shrimp and different types of fish. Every day Emdad Hossein's family bought fresh milk in Keraniganj by the river. He tells that the milk sellers sometimes cheated and diluted the milk with river water, which sometimes left shrimps in the milk.

It is improbable that something like this could happen today. The river is more or less dead and there are no shrimps in the water anymore. Only organisms that can survive in waters with almost no oxygen have a chance of making it in the river. The death of the river is caused by waste water that drains the river of oxygen. The organic waste products are broken down in the water and this process consumes oxygen which results in a very low level of oxygen. The waste water from the tanneries also contains residues of chemicals, such as chromium. This can cause a number of diseases, such as cancer, skin and lung diseases. Emdad Hossein is angry because of the condition of the Buriganga River and because nothing is done about it. He thinks that it is sad that the water is so extremely polluted. “We are proud of the river the same way that people in London are proud of the River Thames. But the way the river is now is terrible. The pollution is very harmful to the animals and to us, especially to poor people who have no alternatives. This is a man-made problem. We have to save the river,” he says. The problems are to some extent seasonal. When the monsoon hits the country the higher water levels help dilute the waste water, and some animals are able to live in the river in this period. Until the dry season returns and the river, the lifeline of Dhaka, once again dies. A member of the Save Buriganga Movement puts it this way:

|