Inside

|

Of Chaos, Confusion and our Constitution SHAKHAWAT LITON goes back in time, tracing the nation's history of constitutional adventures and misadventures.

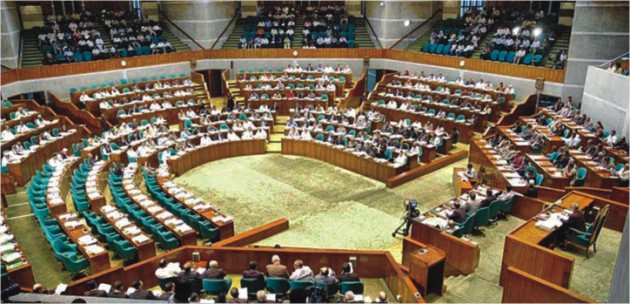

Justice ABM Khairul Haque, in the landmark verdict on the Constitution's Fifth Amendment case, said the modern republican form of democratic government is based on the concept of the right of the people to govern themselves through their own elected representatives. "Those representatives are the agents of the people. They govern the country for and on behalf of the people at large. But those very ordinary people are the owners of the country and their such superiority is recognised in the Constitution," asserted Justice Haque. Haque, now Chief Justice of Bangladesh, was a judge to the High Court Division at the time of delivering the historic verdict in 2005 declaring the Fifth Amendment Act illegal and void. Article 7 of the Constitution stipulates its supremacy and recognises people's power as it says: "All powers in the Republic belong to the people, and their exercise on behalf of the people shall be effected only under, and by the authority of, this Constitution." It also says: "This Constitution is, as the solemn expression of the will of the people, the supreme law of the Republic, and if any other law is inconsistent with this Constitution and that other law shall, to the extent of the inconsistency, be void." The preamble of the Constitution also stipulates its aims and objectives and speaks for its supremacy. "Unlike Preamble of many other countries, the Preamble of our original Constitution has laid down bare in clear terms the aims and objectives of the Constitution and in no uncertain terms it spoke of representative democracy, rule of law, and the supremacy of the Constitution as the embodiment of the will of the people of Bangladesh," the Appellate Division asserted in the case of the Fifth Amendment. About its supremacy, former Chief Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed in the Constitution Eighth Amendment case said that "validity of a law is tested by the touchstone of the Constitution: but there is no such touchstone to test validity of the Constitution. Its validity is inherent and as such it is unchallengeable." Unfortunately, both the political government and military usurpers disregarded the supremacy of the Constitution and undermined the people's sovereignty in the name of amendments since 1973. Of the total of 14 amendments made until 2004, only the eleventh and twelfth amendments got the consensus of both ruling and opposition parties. The most fundamental, and in some cases nefarious, of those changes were brought through the fourth, fifth, seventh, and eighth amendments. Many changes made with ulterior motives largely destroyed the basic structure of the Constitution and also damaged the parliament's power and pre-eminence. In bringing amendments, the political and military rulers did not pay heed to the true spirit of amendment of the Constitution. In fact, the purpose of the two infamous amendments -- fifth and seventh -- was to hide and legalise illegal acts of military dictators of the two martial law regimes. Therefore, the amendments contributed little for further advancement of the country's citizens and further refinements of their constitutional position. Rather, successive governments abused the parliament's authority in some cases to amend the Constitution. Article 142 gives power to parliament to amend any provision of the Constitution by way of addition, alteration, substitution or repeal. Legal experts state a constitution is meant to be permanent, but as all changing situations cannot be envisaged and amendment of the Constitution may be necessary to adopt the future developments, provision is made in the Constitution itself to effect changes required by the changing situations. "Addition, alteration, substitution or repeal are merely modes of amendment and if the act done does not come within the meaning of 'amendment,' it will not be valid, notwithstanding that all the procedural requirements have been fulfilled," said former attorney general Mahmudul Islam in his book titled Constitutional Law of Bangladesh. He said that, when a legislature, which is a creature of the Constitution, is given the power of amendment, it is a power given not to subvert the Constitution, but to make it suitable to the changing situations. But, nothing was able to prevent the political governments and particularly military rulers from undermining the supremacy of the Constitution. In doing so, military rulers followed the path of their predecessors of the Pakistan era. They did not hesitate to commit heinous crimes against the nation and people by destroying constitutional rule. "If the Constitution is wronged, it is a grave offence of unfathomed enormity committed against each and every citizen of the republic. It is a continuing and recurring wrong committed against the republic itself. It remains wrong against future generations of citizens," the Appellate Division stated in a watershed ruling upholding the High Court verdict on the Constitution's Fifth Amendment case. The basic structure of the Constitution On the question of basic features, Justice BH Chowdhury in the Eighth Amendment case listed 21 'unique features' of the Constitution and held that 'some' (without specifying which) of the said 21 features are the basic features of the Constitution. Justice ABM Khairul Haque in the Fifth Amendment case held that sovereignty of the people, supremacy of the Constitution, rule of law, democracy, republican form of the government, unitary state, separation of powers, independence of judiciary, fundamental rights and secularism are the basis of the Constitution. Haque also stated that the Constitution is the supreme law in Bangladesh, all functionaries of the republic are the creatures of the Constitution and the existence of the country as a republic is dependent on its Constitution. Questions have arisen on many occasions on whether the legislature, in exercise of the power of amendment granted by a constitution, can alter or repeal any basic structure or feature of the Constitution. Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed held that the structural pillars of the Constitution stand beyond any change by amendatory process. Amendment will be subject to the retention of the basic structure. The court, therefore, has power to undo an amendment if it transgresses its limit and alters a basic structure of the Constitution, he asserted. "I think the doctrine of bar to change of basic structure is an effective guarantee against frequent amendments of the Constitution in sectarian or party interest in countries where democracy is not given chance to develop," said Ahmed. Although Justice BH Chowdhury did not specify the basic principles of the Constitution, he stated that they are not amendable by the amending power of Parliament. In the Eighth Amendment case, Justice ATM Afzal accepted a limited and highly restricted concept of 'basic features.' He held that the word 'amendment' has a built-in limitation in that it does not authorise the abrogation or destruction of the Constitution or any of its three structural pillars -- executive, legislature and judiciary -- which will render the Constitution defunct or unworkable. Mahmudul Islam in his book wrote: The Indian Supreme Court also resolved the same question of whether the legislature, in exercise of the power of amendment granted by a Constitution, can alter any basic feature of the Constitution. In several cases between 1973 and 1987, the Indian Supreme Court held that Parliament in exercise of the power of amendment cannot alter the basic structure or features of the Constitution. Constitutional chaos: The Pakistan era Bengali rebels successfully fought many battles against the British forces during the second half of the 18th century. Finally, the great day came -- the Dominion of Pakistan formally came into existence on August 14, 1947. But the dreams of the Bangalees were shattered in no time and the history of Pakistan was writ with palace clique, deception and disappointment. The people of the then East Pakistan discovered that they were reduced to second-class citizens; the creation of Pakistan brought them only a change of rulers and for all practical purposes, East Pakistan had become a colony of West Pakistan. The process started with the delay in framing the Constitution of Pakistan, although in India the Constitution was framed and adopted by the Constituent Assembly on November 26, 1949. When the draft Constitution of Pakistan was ready for approval by the Constituent Assembly, governor general of Pakistan Ghulam Muhammad dissolved the Constituent Assembly in December 1954. Earlier, in April 1953, he unlawfully dismissed Khwaja Nazimuddin and his cabinet although Nazimuddin commanded clear majority in the Constituent Assembly and made another civil servant, Muhammad Ali Bogra, the prime minister. Among others, General Muhammad Ayub Khan, commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Army, joined the cabinet as defence minister. This was the first constitutional mishap of Pakistan as governor general Ghulam Muhammad was only a constitutional head. He had to act on the advice given to him by the prime minister. Under the constitutional instruments -- Indian Independence Act 1947 and the Government of India Act 1935 -- he had no legal authority to dismiss the prime minister, Nazimuddin. In August 1955, Major General Iskander Mirza, the Minister of Interior, took over as governor general, forcing Ghulam Muhammad out of power. Iskander was sworn in as the first president under the 1956 Constitution, which was enforced in the country on March 23 in the same year. The Constitution of 1956 proved to be short lived as on October 7, 1958, in collusion with the commander-in-chief, Muhammad Ayub Khan, Iskander Mirza abrogated the Constitution and declared martial law. General Ayub Khan was appointed CMLA. Ayub Khan ousted Iskander Mirza shortly afterwards, banning political parties and declaring himself president. A new constitution was enforced in 1962 during the era of Ayub Khan. In the face of political agitation, Ayub Khan decided to relinquish the office of the president in February 1969. Muhammad Yahya Khan, commander-in-chief, who had taken an oath to be faithful to the Constitution of 1962 and to Pakistan, however, in disregard of his constitutional and legal duty, abrogated the Constitution and imposed martial law throughout the country by a proclamation issued on March 26, 1969. In the face of strong political agitation, Yahya Khan on March 30, 1970, promulgated the Legal Framework Order and under its provisions, elections were held in December 1970 to the national and provincial assemblies. It was the first general election in erstwhile Pakistan, held in 1970, though by that time, as many as four general elections had already been held in India. The latter had gained independence at the same time but did not experience constitutional misadventures like Pakistan. After much political maneuvering, Yahya Khan summoned the national assembly to be convened on March 3, 1971, following the December 1970 election. But shortly before that, he postponed the session indefinitely. Awami League, the dominant political party of East Pakistan, reacted to this decision very sharply. To meet the situation, the Pakistan army on March 25, 1971 unleashed a reign of terror. The genocide committed by them is one of the worst known in history. As a result, the struggle for political autonomy and economic parity transformed into a war of liberation, which started at the dead of night on March 25, 1971 and independence of Bangladesh was proclaimed. "…Because of unjust war and genocide by the Pakistan authorities, it has became impossible for the elected representatives of the people of Bangladesh to meet to frame a Constitution, although General Yahya Khan summoned the elected representatives to meet on March 3, 1971 for the purpose of framing a Constitution…" reads the formal Proclamation of Independence issued on April 10, 1971, at Mujibnagar. After independence, the Constituent Assembly of Bangladesh was created by the Constituent Assembly Order 1972 on March 22, 1972. The Constituent Assembly consisted of the elected representatives of this country, elected both in the National Assembly and the Provincial elections held in December 1970 and in January 1971 in erstwhile Pakistan. The Constituent Assembly completed its task in a remarkably short period of time and framed the Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh on November 4, 1972. The Constitution commenced on and from December 16, 1972. Considering the past history of constitutional misadventures by the civil and military bureaucrats in Pakistan, the framers of the Constitution felt it necessary to make some declarations in the Preamble and Article 7 and also in some articles, which brilliantly comprehends the entire jurisprudence of constitutional law and constitutionalism in Bangladesh, including the supremacy of the Constitution. But the legacy of Pakistan seemed renewed in the newborn country, destroying the Constitution, the supreme law of the nation.

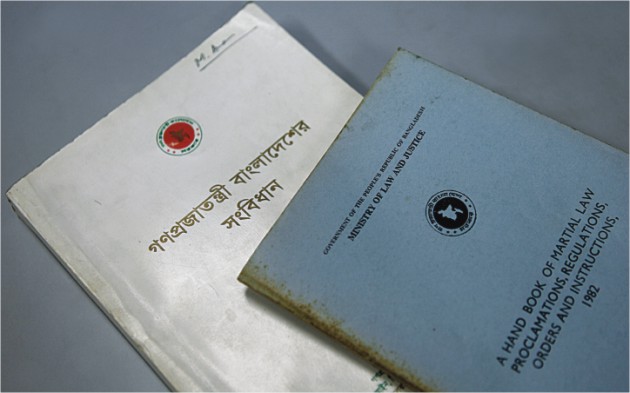

The first cruel attack: 1972-1975 The same year, the same parliament passed the second amendment act in September, introducing a provision for declaring a state of emergency by the president, which was not included in the original Constitution. The amendment also empowered the president to suspend fundamental rights during emergencies. Soon after the second amendment, the then president Mohammad Mohammadullah issued a proclamation of emergency in December 1974, and suspended many fundamental rights of citizens, on advice of the then Prime Minister Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The emergency was lifted five years later in November 1979. In November 1974, the first parliament brought in the third amendment as well, changing Article 2 concerning the territory of Bangladesh. The amendment was made to implement the treaty signed between Bangladesh and India in July 1974 on demarcation of border areas and exchange of enclaves. The first Jatiya Sangsad constituted through the maiden parliamentary election in the newly independent country in 1973, also launched the first cruel attack on the Constitution through passing the fourth amendment act in January 1975. "The first three amendments do not appear to have altered the basic structure of the Constitution. But the fourth amendment of the Constitution clearly altered the basic structure of the Constitution," the Appellate Division of Supreme Court observed in the case of Hamidul Huq Chowdhury v Bangladesh. Analysing the impact of the fourth amendment, former Chief Justice Mustafa Kamal in his book titled Bangladesh Constitution: Trends and Issues, said the amendment changed the basic structure of the Constitution. He said the fourth amendment introduced a presidential form of government led by an all-powerful president, abolishing the parliamentary form of government. "The fourth amendment made a drastic inroad into the independence and jurisdiction of judiciary. A one-party state was established," Justice Kamal added. It also forced elected members of the first parliament to join the only national party within a time specified by the president to save their memberships. One could not even contest in presidential or parliamentary elections if he or she was not nominated by the national party titled Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BKSAL). The fourth amendment also empowered the president to issue an order to dissolve all political parties in the country, and take necessary steps to form the national party, including determining all matters relating to the nomenclature, programme, membership, organisation, discipline, finance, and function of the party. The amendment also allowed the executive branch of the state to control the lower judiciary. The then government however did not get much time to enforce the fourth amendment, as on the morning of August 15, 1975, new president Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated and his government was overthrown. The newborn nation plunged into a disaster and constitutional crisis just over three and a half years into the bloody struggle which put it on the world map. A dark episode: 1975-1979 By a proclamation issued by Moshtaque on August 20, 1975, the Constitution continued to remain in force, but was made subject to the martial law proclamation and martial law regulations, which were totally out of the ambit of the Constitution. Thus, the supremacy of the Constitution was fully ignored and it was made subservient to the martial law instruments, starting a legacy of military rule in sovereign democratic Bangladesh. The then chief justice MA Sayem, who was bound by oath to preserve, protect and defend the Constitution, assumed the office of president on November 6, 1975, by disgracing the Constitution. Two days later he also assumed the powers of chief martial law administrator (CMLA). The first parliament had already been dissolved with effect from November 6, 1975, by the extra-constitutional usurpers of state power. Sayem handed over the office of CMLA to the then chief of army Major General Ziaur Rahman on November 29, 1976, and handed over the presidency to him as well on April 7, 1977. The HC in the Fifth Amendment verdict observed that it cannot be believed that Khandaker Moshtaque Ahmed, Justice Sayem and Major General Ziaur Rahman did not know that under Article 48 of the Constitution, they were not eligible to become the president of Bangladesh. In defiance and violation of the Constitution, they seized the office of president, the highest position in the republic, by force, thereby apparently committing the offence of sedition. The verdict also said it cannot be believed that they were not aware that the Constitution or the laws of Bangladesh do not provide for martial law or the office of the CMLA. They in violation of the Constitution merrily assumed such position and continued to issue proclamations of martial law, martial law regulations and the martial law orders as if Bangladesh was a conquered country. They did not stop by grabbing state power by assuming the office of the president; they even began amending the Constitution at will through martial law proclamations. Changes made to the Constitution in around four years after the August 15, 1975 changeover altered the fundamental principles of state policy, destroyed the secular character of the Constitution and allowed politics based on religion and replaced Bangalee nationalism with Bangladeshi nationalism. Article 8 of the original Constitution, which speaks of the four fundamental principles of state policy -- nationalism, socialism, democracy and secularism -- was amended with the omission of secularism and insertion of the words "absolute trust and faith in Almighty Allah". The amendment omitted Article 12, which contained secularism and freedom of religion. Socialism and freedom from exploitation in Articles 9 and 10 were substituted by the concepts of promotion of local government institutions and participation of women in national life. The principle of socialism was also given a new explanation, saying, "socialism would mean economic and social justice." "These changes were fundamental in nature and changed the very basis of our war for liberation and also defaced the Constitution altogether," the HC observed in its verdict on the Fifth Amendment case. The changes transformed secular Bangladesh into a "theocratic state" and "betrayed one of the dominant causes for the war of liberation of Bangladesh." Omission of the proviso to Article 38 of the Constitution, which banned politics based on religion, radically altered the nature of political activities in the country. It led to the rise of religion-based political parties, which were Constitutionally banned immediately after the independence for their anti-liberation role. The Constitutional bar on war criminals convicted under Bangladesh Collaborators (Special Tribunal) Order 1972 from becoming voters and contesting parliamentary elections was also lifted. Some other fundamental changes to the Constitution were also brought. The preamble to the Constitution was preceded by "Bismillah-ar-Rahman-ar-Rahim" (in the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful). The preamble also underwent two changes -- the words "a historic struggle for national liberation" were replaced with "a historic war for national independence", and "nationalism, socialism, democracy and secularism" were replaced with "absolute trust and faith in Almighty Allah, nationalism, democracy and socialism meaning economic and social justice". Justice Kamal observed that the first martial law regime destroyed and damaged some basic features of the Constitution, while also dismantling the effects of the fourth amendment brick by brick. Ziaur Rahman founded a political party, BNP, which came to power through a general election in 1979 with over a two-third majority in the second parliament, and passed the Fifth Amendment act ratifying all orders and actions made or taken under martial law proclamations, regulations, orders, etc., during the first martial law regime between August 15, 1975 and April 9, 1979. "Thus, in enacting the Constitution (Fifth Amendment) Act, 1979, a colourable legislation, a fraud was committed upon the people of Bangladesh," the HC observed in the Fifth Amendment case. A country without a constitution: 1982-1985 Hilaire Barnett, reader in law, Queen Mary, University of London, in her famous textbook styled Constitutional and Administrative Law, analysed Paine's definition of constitution. She wrote: from this definition, it can be discerned that a constitution is something, which is prior to government, or, as Paine expresses it, 'antecedent' to government, giving legitimacy to the government and defining the powers under which a government may act. What Paine believed over 200 years ago or eminent British public law expert Hilaire Barnett explained in recent times did not mean enough to a Bangladeshi army general, HM Ershad, to prevent him from seizing state power and suspending the country's Constitution. The then chief of army staff seized state power, overthrowing elected president Abdus Sattar in a military coup and imposed martial law throughout the country on March 24, 1982. He declared himself the CMLA, suspended the Constitution -- the supreme law of the land, dissolved the parliament and the council of ministers appointed by Sattar. He also proclaimed himself commander-in-chief of the armed forces -- a constitutional position always held by an elected president. CMLA Ershad announced that the martial law regulations, orders and instructions to be made by him would be the country's supreme law and sections of other laws inconsistent with them would be void. Ershad had installed Justice Abul Fazal Mohammad Ahsanuddin Choudhury as the president on March 27, 1982, as if the general had conquered the office of the president. Ahsanuddin did not have any authority as the martial law proclamation categorically said the president would not exercise any power or perform any function without advice and approval of the CMLA. Ershad vested the executive power in the CMLA through a regulation on April 11, 1982, paving the way for him to exercise power either directly or through people authorised by him. The April 11 regulation also vested legislative powers in the CMLA. He took the authority to revive the Constitution fully or partially. But, if the Constitution was revived, its enforcement was subject to the martial law proclamation, regulations and orders made by the CMLA. However, the general was not satisfied with the power and office he held. He forced president Ahsanuddin to resign on December 11, 1983 and assumed the office of the president the same day in addition to the post of CMLA. The Supreme Court ceased to derive any power from the Constitution which was suspended following the March 24 proclamation. People's fundamental rights were suspended. They were not allowed to go to court seeking remedy against violation of any right. Through an amendment to the martial law proclamation, Ershad seized the power to make appointments to constitutional posts of the chief justice and judges of the Supreme Court, the chief election commissioner and commission members, comptroller and auditor general, the chairman and members of the Public Service Commission. A person appointed to any constitutional post would have to take oath to perform duties with honesty in accordance with the March 24 martial law proclamation. After ruling the country for over three years, with the Constitution completely suspended, the general seemed to have understood the legal philosophy of Thomas Paine and Hilaire Barnett as he desperately tried to give legitimacy to his regime. He held a farcical public referendum with a said voter turnout of 72 percent on March 21, 1985 which claimed that Ershad obtained 94.14 percent "yes votes" in favour of his rule. But the outcome of the referendum could not ensure legitimacy of the military government led by Ershad. Therefore, he started reviving the Constitution from mid-1985 in phases, exercising his power as CMLA. The total revival of the Constitution came on November 10, 1986 when martial law was withdrawn by a proclamation. But before the final revival, the military ruler left no stone unturned to ensure legitimacy of his rule. In August 1986, he stepped down as chief of army staff and formally joined the Jatiya Party (JP), which was floated under direct patronisation of the then military government. The regime organised the third parliamentary election on May 7, 1986 and the government-sponsored JP won majority in the poll widely criticised for electoral irregularities. In October of the same year, 1986, the military regime organised the presidential elections in which Ershad contested as JP candidate and emerged victorious from the polls boycotted by all major political parties. The Jatiya Sangsad constituted through the third parliamentary election passed the Constitution's Seventh Amendment Act on November 10 of 1986, ratifying the March 24 proclamation and validating all orders and actions made under the proclamations, regulations and orders. Like the Fifth Amendment Act, the seventh amendment also precluded the court's jurisdiction from reviewing any action of the military regime led by Ershad, violating the basic structure of the Constitution. For the good of some . . . "Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Father of the Nation, shall become, and enter upon the office of President of Bangladesh and shall, as from such commencement, hold office as President of Bangladesh as if elected to that office under the Constitution as amended by this Act," reads the special provision of the Fourth Amendment Act. With this amendment to the Constitution, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman became president on January 25, 1975. Mohammadullah, who was elected president on January 24, 1974, and took oath of office as president on January 27 of the same year, had to resign on January 25, 1975, to clear the way for Bangabandhu to become the president. Another special provision of the Fourth Amendment Act extended tenure of the first parliament -- which was constituted through elections held at the end of 1973 for five years -- by at least one year, allowing members of parliament (MPs) to remain in office for one year longer than their original tenure. The Constitution's Sixth Amendment Act was passed by the second parliament in July 1981, allowing the then vice-president Justice Abdus Sattar to contest in the presidential elections held in November of the same year, while in office. Justice Sattar, who became the acting president after the assassination of President Ziaur Rahman on May 30, 1981, contested the presidential elections as a Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) nominee and was elected to the office of president. The third parliament passed the Constitution's Ninth Amendment Act in 1989, introducing the office of vice-president. After the amendment, the then president HM Ershad appointed Moudud Ahmed as vice-president. It is said that the office of vice-president was introduced only for Moudud Ahmed. Military ruler-turned-president HM Ershad resigned from the post on December 6, 1990, in the face of a tumultuous mass upheaval against his government, appointing Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed, the then chief justice, as the vice-president, since the incumbent vice-president had resigned earlier. The newly appointed vice-president exercised the powers and performed the functions of the president, and a parliamentary election was held under his supervision in February 1991. The fifth parliament, constituted through the 1991 elections, passed the Eleventh Amendment Act in August the same year, to ratify Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed's appointment as the vice-president, and the powers exercised and laws and ordinances made during the tenure. The amendment, which was made on consensus of both ruling and opposition parties, also allowed him to resume the duties and responsibilities of the chief justice after a new president would be elected under the Constitution. The eighth parliament, dominated by the BNP-Jamaat alliance, passed the Fourteenth Amendment Act in 2004, increasing the number of women's reserved seats in parliament from 30 to 45. The amendment, however, generated controversy as it also increased the service age of Supreme Court judges by two years. The then opposition parties alleged that the government increased the service age of judges to make it legal for the then Chief Justice MA Hasan to lead the upcoming caretaker government that would assist the Election Commission to hold the ninth parliamentary elections. The opposition camp vehemently refused to accept Justice Hasan as the caretaker chief. The political situation became volatile by the end of 2006. The latest constitutional misadventure took place when the then president, Iajuddin Ahmed, assumed the office of the chief adviser to the caretaker government in violation of the Constitution. A state of emergency was declared in January 2007, leading to suspension of the ninth parliamentary elections scheduled for January 22. The eventful and prolonged emergency regime ended through holding of the ninth parliamentary elections on December 29, 2008.

The loss of parliamentary power Some reasonable restrictions were however imposed on members of the parliament, to prevent floor crossing, for the stability of the government. The legislature was also empowered to remove constitutional officers such as the judges of the Supreme Court, the chief election commissioner, election commissioners, the chairman and members of the Public Service Commission, and the comptroller and auditor general -- on grounds of misconduct and incapacity. According to the original Constitution, the country was to always have a functioning elected parliament. But over the years, many of the powers of the parliament were curbed and it has largely lost its pre-eminence due to some changes brought to the Constitution by the fourth, fifth, twelfth and thirteenth amendments. The amendments brought by both military rulers and elected governments, not only eroded the parliament's power, it also made the House subservient to the chief executive in some cases. The process of undermining the parliament's supremacy began with the fourth amendment brought by the Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman-led government in 1975, imposing one-party rule and switching form parliamentary to presidential form of government. Although the parliament remained in place, its legislative authority became a captive of the president's veto power. After his death in 1975 to 1990, the country was governed by military rulers either directly or indirectly under cover of civilian rule, who also opted for the presidential form of government. Although democracy and the parliamentary system were restored in 1991 through the twelfth amendment, the House did not get back its original power and status. The fourth amendment took away the parliament's power to remove constitutional officers, and bestowed the authority on the president instead. The first military regime changed that through a martial law proclamation, and introduced a new procedure for removal of such officers by the Supreme Judicial Council, a system that exists in Pakistan.

While the Supreme Court recently declared illegal and void the Constitution's fifth amendment which ratified all actions of the first military regime between August 15, 1975 and April 9, 1979, the judgment condoned the introduction of the Supreme Judicial Council in order to prevent revival of the relevant provision of the fourth amendment. In defence of its move, the apex court said that the Supreme Judicial Council is a more transparent procedure for removal of constitutional officers, which safeguards the independence of the judiciary. The fourth amendment tightened the restrictions on MPs, making them unable to play their due role in the parliament freely. It also instructed for only two parliamentary sessions in a year, in contrast to the original Constitution's direction allowing only a maximum of 60 days' gap between the end of a session and the beginning of the next one. The subsequent military rulers did not bring any change to these fourth amendment clauses. The twelfth amendment in 1991 brought back the original provision of the Constitution regarding the matter, but at the same time it increased the restrictions on MPs some more. "[Original] Article 70 puts a reasonable restriction on the function of a member of parliament, but the amended article 70 makes him a prisoner of his party," the Supreme Court observed in a verdict on April 27, 2006. Due to the restrictions on MPs, the parliament's ability to ensure accountability and transparency of the executive branch has been reduced, although the cabinet is Constitutionally collectively responsible to the House. Lawmakers of the treasury bench cannot cast votes against any government decision, and no lawmaker can abstain from voting unless his or her party decides to do so, nor can he or she cast votes when the party decides to abstain from voting.

The provision gave rise to an all-powerful prime minister in the parliamentary form of government, who, according to critics, turned into a "parliamentary dictator". The premier, usually the chief of a ruling party, simultaneously holds the office of the leader of the House. In this capacity, the premier picks MPs of his or her choice to lead the parliamentary standing committees, which are assigned to ensure the executive branch's accountability to the parliament. The prime minister's absolute control over the treasury bench makes it impossible to bring a no-confidence motion in the House against the cabinet. The fourth amendment, on the other hand, had made the then president all-powerful, empowering him or her with the authority to veto any bill passed by the House. The Appellate Division of Supreme Court in its recent judgment, nullifying the fifth amendment, observed that the fourth amendment had reduced the parliament's power. Although the first martial law regime dismantled many provisions of the fourth amendment, it kept the president's sweeping power intact. In some cases, changes to the Constitution during the regime increased the already too powerful president's authority. The Supreme Court observed that the changes made the parliament subservient to the president. It said that, under the fifth amendment, if the parliament failed to make grants or to pass an annual budget, or refused or reduced demands for grants, the president could dissolve the parliament at his or her pleasure. Thus the president and CMLA of the first martial law regime, Maj Gen Ziaur Rahman, became an all-powerful chief executive without any check either from the parliament or any other state apparatus, the apex court observed. Following Zia's assassination, Gen Ershad grabbed state power and declared himself the president, enjoying similar sweeping authority during his entire tenure up to December 6, 1990. Although the twelfth amendment in 1991 restored the parliamentary system of government replacing the presidential form, it kept intact the fifth amendment-ratified martial law regulation that allowed the president to promulgate ordinances when the parliament stood dissolved. And the retention of that fifth amendment provision kept the parliament's exclusive legislative power still a distant dream. The original Constitution did not allow the president such a sweeping legislative authority, except for promulgation of ordinances on urgent financial matters, while parliament would stand dissolved. It also allowed the president to promulgate ordinances on any urgent matter when a functioning parliament would not be in session. The president's sweeping legislative power, allowed by the fifth amendment, was declared illegal and void by the apex court's recent judgment. Finally, the thirteenth amendment in 1996 introduced the caretaker government system, against a backdrop of agitation by Awami League (AL) and an electoral stalemate between AL and BNP, making the parliament non-existent for at least three months prior to a parliamentary election. During this period, the state does not function as a republic, as an un-elected government runs the country without any parliamentary scrutiny. The original Constitution had provisions for holding a parliamentary election within 90 days prior to normal dissolution of a parliament. But the thirteenth amendment introduced the provision that the caretaker government would assist the Election Commission in holding parliamentary polls within 90 days following a parliament's dissolution. The road ahead The Supreme Court in the Fifth Amendment verdict strongly denounced martial law and suspension of the country's Constitution, and recommended meting out suitable punishment to the perpetrators. "The perpetrators of such illegalities should also be suitably punished and condemned so that in future no adventurist, no usurper, would dare to defy the people, their Constitution, their government, established by them with their consent," said the Appellate Division upholding the High Court Division's historic ruling of 2005 that had declared the fifth amendment to the Constitution illegal. It also said that military rule was wrongly justified in the past, and it should not be justified in future on any grounds. "Let us bid farewell to all kinds of extra Constitutional adventure forever. It is up to the parliament to enact laws to prevent martial law," it observed. Following the cancellation of the fifth amendment, the government moved to bring necessary amendments to bring back the spirit of the original Constitution. A parliamentary special committee was formed to examine the Constitution and prepare proposals to this effect. People expect the special committee to work efficiently to establish supremacy of the country's Constitution, which is the embodiment of the people's will. In line with the apex court's observation, the special committee is considering recommendations which include a stringent provision in the Constitution to prevent extra-constitutional takeover in future. However, political parties and politicians must understand that constitutional provision alone cannot prevent extra-constitutional takeover. Pakistan is a glaring example of this. Even in independent Bangladesh, the supremacy of the Constitution could not prevent military rulers from grabbing state power by declaring martial law. Only by strengthening democratic practice everywhere can this be ensured. As Abraham Lincoln said: "Ballots are the rightful and peaceful successors of bullets." Shakhawat Liton is Senior Reporter, The Daily Star.

|