Inside

|

The Courts to the Rescue JULFIKAR ALI MANIK and KAJALIE SHEHREEN ISLAM reflect on the rising trend of going to court to ensure fundamental rights guaranteed in the Constitution.

Something was wrong. "Wherever we went, people were saying, 'Bangabandhu has declared independence!'" says Dr MA Salam, recalling the days after March 26. Thus, when 38 years later, he came across documents which claimed a history -- of which he had been a part -- that was unknown to him, he knew that it had to be wrong. Thinking it to be a printing error, Salam sent a notice to the government asking that it be corrected, but there was no response. In April 2009, challenging the distortion of history in the documents of the independence war, Dr MA Salam went to court. Earlier that year, Salam had found written in a section of the15-part History of Bangladesh War of Independence: Documents, a government publication edited by Hasan Hafizur Rahman, that Major Ziaur Rahman had proclaimed the independence of Bangladesh on March 27, 1971. When he compared it to the first edition of the same documents published in 1982, he saw that certain changes had been made. In the 2004 edition, the fact that independence had been declared on behalf of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had been deleted and the proclamation was credited to Ziaur Rahman himself. Salam says that he had heard such propaganda before, on the streets, in political meetings; but when he saw it in written text, he knew something had to be done. On June 21, 2009, the High Court ruled that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had proclaimed the nation's independence on March 26, 1971. "It was a historical fact and there should have been no debate about it," says Dr MA Salam, "The change was a gross distortion of history and it had to be corrected. As a freedom fighter, as a good citizen of this country, it was my duty to protect our history for our children to learn." If the relevant authorities had done their duty, however, says Salam, he would not have had to go to court, the last resort.

The question of good governance, that is whether the relevant authorities are discharging their duties and ensuring people's rights and services, has come to the fore in recent years. A myriad of issues has been placed before the courts and the latter, too, have had to rule on various matters in an effort to address the grievances of people long deprived of basic rights and facilities. The list of issues ranges from the individual to the national, from the social to the political, from issues of public health to personal faith. It starts from basic rights and ends up endangering personal freedoms. While government bodies exist to protect these rights and provide these facilities, people have had to seek legal intervention in matters as basic as the supply of pure and safe food and water. The courts have become the last place of refuge for deprived citizens. Eminent jurist and constitutional expert Dr Kamal Hossain observes that some people are over-enthusiastic about going to court. "Others, however, are forced to, due to the failure of different bodies to deliver and fulfil their responsibilities. The courts, rather than always dealing with them directly, must create pressure on the relevant organs to make them perform," he says. This failure to deliver not only causes unnecessary agitation but also puts lives at risk. Fish containing formalin, fruits and vegetables containing chemicals, water contaminated by bacteria, are some of the most basic concerns of ordinary citizens. There are government bodies whose duty is to regulate and monitor these processes, but with people having to take legal recourse, their effectiveness has become highly questionable. It is the courts that had to order the Bangladesh Standards and Testing Institute (BSTI) as well as law-enforcing agencies to monitor fruit depots in Dhaka to prevent the storage and selling of adulterated fruits, while the National Board of Revenue was ordered to stop the import of contaminated fruits. The courts also directed the government to set up food courts and appoint food analysts and inspectors in every district in order to check adulteration of food. Manzill Murshed, an advocate of the Supreme Court, has been going to court continuously demanding basic services. His belief is that if government and administrative bodies fail to do what they are legally bound to do, people or organisations can go to court in the interest of the public to make them perform their duties.

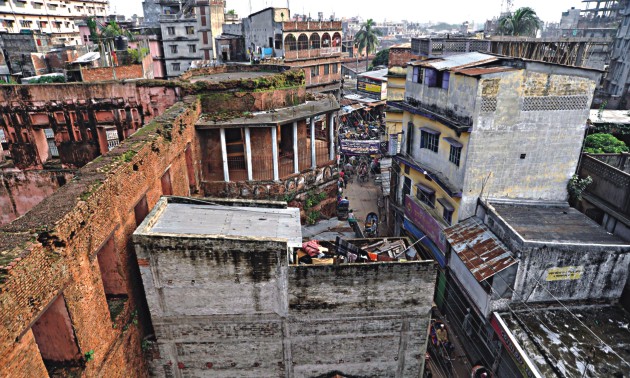

In terms of filing the cases, one thing led to another, says Murshid. Contaminated drinking water is a common problem, against which he filed a case. This made him think about the source of the water, leading to the waste disposal which pollutes the Buriganga river, on which another case was filed. Contamination is not the only problem with Dhaka's rivers, however. Saving Dhaka's lifeline of four rivers has become an issue in itself, requiring serious intervention of the courts. Encroachment, construction of illegal structures on the banks and even in the middle of the rivers and pollution have all put them at risk, causing the court to order the deployment of police to guard the banks of the Buriganga. Not only rivers but even the seaside is having to be saved by the courts, with the cancellation of plot allotments on the beaches of Cox's Bazaar in order to maintain ecological balance. Environmental concerns have also been raised in the ship-breaking yards in Chittagong where the activities are not only a threat to the workers but also to the ecosystem. Environmental groups have had to go to court repeatedly to compel the authorities to take measures to protect the environment. Neither water, nor land is safe in our country. It took a court directive to prevent cattle markets being set up on the streets of the capital during Eid-ul-Azha and to ensure the proper disposal of the animals' remains, in order to prevent environmental pollution. In an increasingly consumerist society, it has taken several tragic incidents of injury and death to bring to the notice the potential hazards of humungous billboards -- many of them unauthorised -- all over as well as outside the city. After an exchange of writ petitions and stay orders, the High Court ordered the dismantling of unauthorised and hazardous billboards, a matter which should have been monitored by the relevant city authorities. Billboards are not the only dangers on the streets, however. Over the decades, many people have made news headlines after being electrocuted by torn and hanging electric wires which were not properly maintained. The sound of transformers exploding too, is a common phenomenon in the city. But it was only after the devastation in Nimtali earlier this year that the negligence of institutions in the power sector was brought to people's notice and, following the filing of a case in this regard, the courts ordered the relevant authorities to examine the city's transformers. The courts have also had to rule to ensure the security before natural and other disasters occur after social groups demanded the procurement of adequate fire-fighting and other rescue equipment necessary in the event of a major earthquake and other disasters and accidents. While the streets may be hazardous, institutions are not safe either. Human rights groups have had to go to court challenging the "systematic failure" of the government to take action against cases of corporal punishment at schools. When a female headmistress of a school was called a "prostitute" by an education ministry official for not covering her head, it took a court directive to declare that women working at public or private educational institutions may not be forced to wear the veil, that covering their heads is their personal choice and that forcing them to do so is a violation of fundamental rights as enshrined in the Constitution. Extra-judicial punishment such as fatwa have also had to be declared illegal by the courts. The High Court has also issued guidelines against sexual harassment at educational institutions and the workplace, which are yet to be made into law. From ensuring safety and fundamental rights to protecting sanctity, the courts have also had to take responsibility for upholding the inviolability of the Shaheed Minar, asking the government to take steps so that functions and meetings are not held in the bedi or main part. The courts have had to order for the protection of Lalbagh Fort, a historic site on which multi-storied buildings have been constructed. Recent media reports, however, show that people are still occupying the land of the fort, defying the courts' orders. One is not safe even in death, with court orders needed to stop the construction of a road through Azimpur graveyard.

The list is endless. But, while the problems are not new, recent initiatives by aware and concerned citizens and organisations seeking legal remedies have gained popularity. Under Article 102 of the Constitution, the High Court Division may give "directions or orders to any person or authority, including any person performing any function in connection with the affairs of the Republic, as may be appropriate for the enforcement of any of the fundamental rights conferred by Part III of th[e] Constitution" and may also direct "a person performing any functions in connection with the affairs of the Republic or of a local authority to refrain from doing that which he is not permitted by law to do or to do that which he is required by law to do". With the authorised bodies failing to deliver, people and organisations have been forced to choose the last resort -- the courts. Public interest litigation or PIL is becoming increasingly popular in developing nations such as India and Pakistan where good governance is an everyday battle. "This is because people here do not abide by the law," says Advocate Manzill Murshid. "If they followed the law and performed their duties then there would be no need for PIL." However, in developed nations such as UK and US too, PIL is popular in terms of issues such as the environment. With the recent surge in litigation in Bangladesh, however, PIL has come under some criticism. But, for people like Murshid, also president of Human Rights and Peace for Bangladesh (HRPB), going to court seems to be the only way to ensure one's basic rights. "It is a relatively new trend and is thus attracting people's attention, some negative, but it is for the good of the people and society," he says. Barrister Amir-Ul Islam, too, sees the rise in PIL as a healthy trend. "It is a part of the process of a growing democracy, encouraging rule of law and governance," says the eminent jurist. "Every new democracy as it appears has gone through the process; for example, in India the role of PIL has reached its zenith." There is a question of how far the courts should be involved in governance issues, says Islam, but when people are denied and deprived of certain fundamental rights, there can be a role of an intervener, where non-governmental organisations (NGOs) can be effective in addressing these maladies. However, there are certain risks in PIL cases, with people and organisations taking their professional rivalries to court.

"PIL has at times been abused and the courts should be extremely careful in this regard," says Islam. "PIL cases should be backed by enough research and the groups filing them should have a credible track record of working in these areas. Groups which file them must devote time for research on the issues they are fighting for before taking them to court. Genuine groups should also be generously supported by the community." An institutional framework should be developed -- the more specialised the NGOs are, the better they will perform, opines Islam. Only if genuine and well-researched cases are taken to the courts can the courts help to address the issues before it. While public interest litigation may be a sign of increased social consciousness in a growing democracy, it is also a clear sign of bad governance in that society. Settled historical matters fall victim to political controversy; legal recourse is sought for unaddressed personal and public grievances instead of their being dealt with by the authorised organs of the state. While critical analysis of public interest litigation is understandable, given our social reality, the practice is a positive one. It can only be reduced by ensuring good governance, where those responsible for ensuring rights and services to the people fulfil their duties. Julfikar Ali Manik is Chief Reporter, The Daily Star.

|