Inside

|

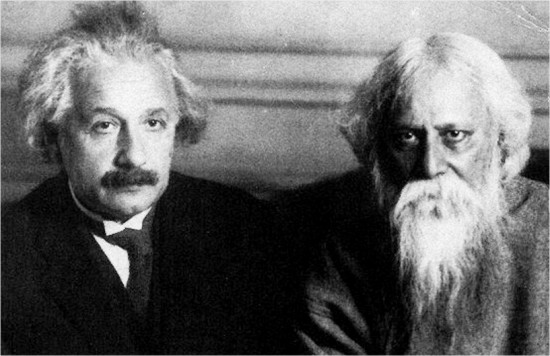

Nationalist, Anti-Nationalist or Beyond Nationalist? Shamima Nasreen presents Tagore as a thinker for the world Rabindranath Tagore had sensible and clearly articulated views about nationalism in the light People may be confused by Tagore's description of his Bengali family as the product of "a confluence of three cultures, Hindu, Mohammedan, and British," because the amalgamation of East and West may seem contradictory. Actually, Tagore did not support the idea of nationalism. Tagore's Concept of Nationalism and Universal Humanity Tagore's strongest expression comes not in nationalism but in creativity. The connotations of the term "nationalism" have changed a good deal since 1916. Tagore has little to say about ethnic cultures, or about linguistic or religious communities or nationalist myths. His definition of a nation is the political and economic union of a people in that aspect that a whole population assumes when organised for a mechanical purpose. The emphasis falls upon organised and mechanical. The western nation is conterminous with the nation-state, the mechanical organisation of people in pursuit of material enhancement and hence aggressive and imperialist in character; in fact, for nationalism we might often read imperialism. At other times, Tagore in his distrust of technology and impersonal bureaucracy, falls into a similar position to the western romantic critique of civilisation and modernisation as he said: "When this organisation of politics and commerce, whose other name is the nation becomes all-powerful, at the cost of the harmony of the higher social life, then it is an evil day for humanity …This abstract being, the nation, is ruling India." This is very interesting that his thought continually moves between opposites -- spiritual and materialist, East and West, nation and no-nation, masculine and feminine, abstract and personal and then seeks for ways to reconcile and harmonise the opposites. According to him these don't need to compete but should eventually fall into equilibrium. In nationalism this is rarely more than wishful rhetoric. Moreover, Tagore stressed his international concerns, and shrewdly denounced the excesses of nationalism not only in India, but also in Japan, China, and the West. The following concepts and ideas of Tagore dominated his thoughts and principles far more than nationalism. Education for Freedom of Mind Tagore was concerned not only that there be wider opportunities for education across the country (especially in rural areas where schools were few), but also that the schools themselves be more lively and enjoyable. He himself had dropped out of school early, largely out of boredom, and had never bothered to earn a diploma. He wrote extensively on how schools should be made more attractive to boys and girls and thus more productive. For Tagore it was of the highest importance that people be able to live, and reason, in freedom. His attitudes toward politics and culture, nationalism and internationalism, tradition and modernity, can all be seen in the light of this belief. Passion for freedom underlies his firm opposition to unreasoned traditionalism. His uncompromising belief was in the importance of "freedom of mind." Anti-war Notion Throughout his adult political life, Rabindranath Tagore had been critical of using force, man against man, class against class, nation against nation. He had sharp words for the Japanese when he visited Japan at the time of the First World War and in the late 1930s; he was hostile towards their use of force in China. Cultural Convergence

Tagore and Patriotism Tagore's criticism of patriotism is a persistent theme in his writings. His novel Ghare Baire (The Home and the World) has much to say about this theme. In the novel, Nikhil, who is keen on social reform, including women's liberation, was cool towards nationalism, gradually loses the esteem of his spirited wife, Bimala, because of his failure to be enthusiastic about anti-British agitations, which she sees as a lack of patriotic commitment. Bimala becomes fascinated with Nikhil's nationalist friend Sandip, who speaks brilliantly and acts with patriotic militancy, and she falls in love with him. Nikhil refuses to change his views: "I am willing to serve my country; but my worship I reserve for Right which is far greater than my country." As for the contrary evidence of Tagore's "patriotic" gesture, such as his renunciation of his knighthood, Tagore believes in protesting against injustice in the name of humanity, not in the hope of gaining concession. Tagore was the only one whose protests were motivated by a sense of moral duty. Rabindranath's qualified support for nationalist movements -- and his opposition to the unfreedom of alien rule -- came from the commitment that freedom is one of the most important priorities. Thought on Politics and Civil Society Tagore, says E.P. Thompson, "was a founder of anti-politics." This means that even during the phase of the most widespread political activities in India's struggle for independence, Tagore continued to maintain that village reconstruction in the dream to make a civil society was a more fruitful activity for the purpose of the real deliverance of the Indian people. Tagore's commitment to anti-politics and his concern with civil society make him appear at times to be a markedly modern -- or perhaps postmodern thinker. The assertive nationalisms and communalisms which mark our own time and which refuse any assent to universal value are not confined to the West. Tagore cannot resolve these problems but if we can share and apply his far-sighted intuitions he may help us do so. Message to his countrymen and support for international cooperation He warned his countrymen against accepting those evils, which the West has brought through the application of the great knowledge-the conquest of the vast spaces of the world and the upturning of man's moral balance, the liquidation of his human side under the shadow of the soulless organisation of the machine. Tagore exhorted: "You must apply your Eastern Mind, your spiritual strength, your love of simplicity, your recognition of social obligation in order to cut out a new path." Criticism of his Beliefs as Anti-Nationalist

Japanese critics suggested that Tagore's praise for the lack of nationalism in India was the special pleading of a "defeated people." Moreover, Tagore's diatribes against materialism, technology, mechanical organisation, and unbridled pursuit of wealth are criticised by many western people. Some people criticise him as saying Tagore had once been a nationalist but had withdrawn from this stance later. Tagore himself had passed through an ardent nationalistic phase in the first years of the century, the years of Swadeshi and of the agitation against the 1905 partition of Bengal, and then fell back into a more quietist stance in the next decade. His novel The Home and the World (1916 in Bengali) belongs to this latter phase, and it testifies to the ambivalence of Tagore's response to Indian Nationalism. Nationalists accused him of apostasy, which seemed to be confirmed when he was awarded a knighthood in 1915; his renunciation of that honour in 1919, however, in protest at the massacre at Amtrisar and its aftermath, did something to repair his patriotic image. No matter what many critics state about him, it is well established that Rabindranath persisted on open debate on all subjects, and were wary of conclusions based on a mechanical formula, no matter how attractive it may seem separately. The question that repeatedly arises is whether we have sufficient reason to want what is proposed, taking everything into account. Important as history is, the reasoning must overshadow the past. As Amartya Sen, Nobel laureate in economics (1998) well described him: "It is in the sovereignty of reasoning -- fearless reasoning in freedom -- that we can find Rabindranath Tagore's lasting voice." In my view, his valiant reasoning in self-determination prevails over extreme nationalism. The present world consists of the several aspects of globalisation that are being practiced through sharing knowledge and cross-cultural views by a globe-spanning network of communication, and it is me, a free mind, who is to decide what it is to acculturate. Shamima Nasreen is an international relations analyst.

|

of cross-cultural knowledge, education for freedom of the mind, war and peace, the importance of reasonable criticism, the need for openness, and so on. His books show the influence of different parts of the Indian cultural background, as well as that of the rest of the world.

of cross-cultural knowledge, education for freedom of the mind, war and peace, the importance of reasonable criticism, the need for openness, and so on. His books show the influence of different parts of the Indian cultural background, as well as that of the rest of the world.