Inside

|

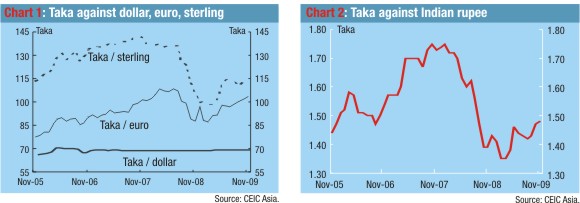

A Fistful of Takas Jyoti Rahman questions the wisdom of pegging to the dollar In its Monetary Policy Statement for the first half of 2010, the Bangladesh Bank promises to keep a "constant watch" on the "build up of price pressures" while continuing the supportive monetary stance to "facilitate the recovery in exports" among other things. Simply stated, this means that the Bank is going to continue with its de facto policy of pegging the taka against the dollar at a "moderately undervalued" rate to support exports. But this policy has seen taka depreciate against the Indian rupee, which in turn is fuelling further inflationary pressures. This leaves the Bank with a tricky policy trade off, the resolution of which will crucially affect every facet of life in 2010 and beyond. Let's work through the story with a set of charts. Chart 2 shows the taka/rupee exchange rate follow a similar trajectory. The snag is, taka's depreciation against euro or sterling can be a good thing for Bangladeshi exports, but depreciation against the rupee is by and large a bad outcome for food prices. Let's address the policy imperatives one at a time.

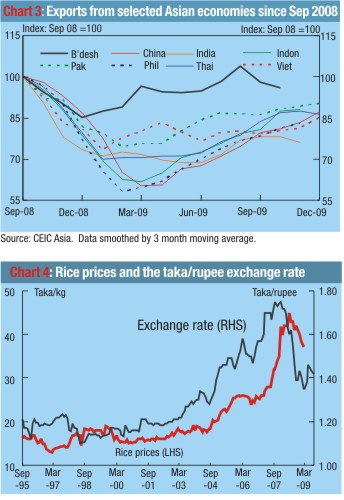

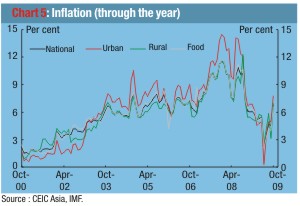

The current exchange rate policy has considerable merit. A "moderately undervalued" taka helps with exports to the United States. Plus, given the large US current account and budget deficits, the medium-term expectation for the dollar is to depreciate, and fixing the taka against the dollar means depreciation against other major western currencies, further boosting our exports. Indeed, this may well be a major factor behind our strong export performance. Within weeks of the global recession hitting its most virulent phase after the Lehman collapse, world trade plunged, and exports from Asia shrunk heavily. But surprisingly, Bangladeshi exports fell by much less. Then it started recovering much earlier than other comparable countries (Chart 3). Our major export competitors like China or Vietnam (but crucially, not India) maintain some form of peg against the dollar. Therefore, the exchange rate policy probably served us well. However, I would argue that because our industry depends on imported raw material and machinery, and an undervalued taka makes these inputs dearer. More importantly, it's not clear how important the exchange rate has been relative to other factors. Particularly, ready-made garments, accounting for two-thirds of our exports, hardly suffered through the recession, whereas other exports such as fish and prawn or leather suffered falls comparable to those from our neighbours. At the onset of the recession, optimists suggested that because our ready made garments exports were geared towards the budget end of the western market, we would be relatively unaffected by the recession. Catering to the bargain basement or an undervalued taka: which has been more important for our remarkable export performance? And, finally, for exports, what matters is real (that is, inflation-adjusted), not nominal, exchange rate. If an undervalued taka leads to inflation in Bangladesh, then taka will have an effective real appreciation, which will hurt exports just as badly as if taka were allowed to appreciate. And indeed, this is what we have seen -- the real effective exchange rate has been appreciating in recent years. Whatever the impact of the undervaluation bias on exports, the effect on food prices is much clearer. Chart 4 shows price of one kg boiled rice in Dhaka against the taka-rupee exchange rate since 1995. There appears to be a pretty good relationship -- taka depreciates/appreciates against the rupee today, and rice prices in Dhaka rise/fall a few months later. Thus, the sharp appreciation of taka during late 2008 were followed by falling rice prices as the new government took office. But since March 2009, the taka has depreciated by over 7 per cent against the rupee, and lo and behold, high rice prices are back in the newspaper headlines. At the time of writing, published rice price data were available only to early 2009. But we know that consumer price inflation was 6.7 per cent in the year ending October 2009, up from 2.2 per cent in the year ending June. The inflation uptick has been broad-based among both rural and urban areas, and it has been driven by a rise in food prices (which account for over two-fifths of consumer price index). Chart 5 illustrates the inflation trend in recent years. By late 2009, inflation was hitting rates seen in 2003-06, when the tales of Hawa Bhaban led corruption circulated widely. No wonder that in the recently conducted Daily Star Nielsen opinion poll, two-fifths believe that prices/agriculture/food security should be the single most important focus for the government. In an article in the Journal of Bangladesh Studies, Zahid Hussain and Sanjana Zaman -- two World Bank economists -- used econometric methods to test how integrated food commodities are between India and Bangladesh. They found that the rice markets in the two countries are "completely integrated." Any change in exchange rate is therefore going to play a major role in food prices -- just as the appreciating taka helped bring inflation down in the first half of 2009, in more recent months, depreciation has been fuelling inflation. Indeed, the Bank acknowledges it implicitly in its statement: "Domestic prices of rice are holding firm even in the post-Aman harvest season, presumably because of much higher prices prevailing in neighbouring India. So, continuing with the current exchange rate policy, while possibly helping exports, will probably fuel inflation. What are the Bank's alternatives then? Pegging against the rupee is a non-starter. In Bangladesh, some people fear "becoming like Nepal or Bhutan" every time a dog barks. Well, pegging the taka against rupee would make Bangladesh like Nepal or Bhutan, who peg their currencies against the rupee. And there are sound macro-economic reasons why we should not become like Nepal or Bhutan in this regard. Since the 1960s, macroeconomists have been aware of the impossible trinity which holds that a country can, at once, achieve only two and never three of the following: fixed exchange rate, capital mobility, and monetary policy independence.

If the taka is fixed against the rupee, this would mean our authorities would have to choose either capital mobility between the two countries, or monetary policy independence. Given weak institutions, it would be practically impossible to restrict capital mobility across our porous border. This means a peg against the rupee will result in effectively ceding monetary policy to the Reserve Bank of India. This won't involve any elaborate state protocol. Most paranoid Indophobes in Dhaka wouldn't probably even notice it. But it would mean every time the RBI changes monetary policy, we would have to match it, regardless of our domestic conditions. If the RBI tightens monetary policy, and we didn't want to because of weak domestic conditions, there would be capital flight and we could be threatened with a currency crisis. Alternatively, if the RBI loosened monetary policy, but we had inflation worries, there would be hot money flowing in, and the inflation problem would worsen. Another option is to let the taka freely float. However, does the Bank have the credibility to operate without a nominal anchor? Only a handful of central banks (most notably the US Federal Reserve) operate without a nominal anchor. Most developed economies are committed to price stability, while many emerging and developing ones choose exchange rate stability. If the taka were to freely float, then the Bank would have to become an inflation hawk. Does the Bank have that credibility? There is a substantial literature of political business cycle theory that shows that in all democracies, governments tend to spend beyond their means before elections. How damaging this vote-buying depends on how strong the economic institutions are, with the central bank being the key institution. Suppose our government were to embark on a pre-election spending spree by 2013-14. Considering the fact that the current governor of the Bangladesh Bank was intricately involved with the political side of the Awami League campaign before the 2008 election, will the market expect such a spending spree to be accommodated with loose money? The only other option left is to peg taka against a basket of currencies. In practice, this will mean allowing taka to appreciate against the dollar and the rupee under the current circumstance. By how much and over how long will depend on what the Bank's analysis shows. While in other circumstances, the policy stance will be different. Such a policy will require detailed analysis, which will have to be conveyed in a concise manner. Is anyone at the Bank listening? Jyoti Rahman is an applied macroeconomist and a member of Drishtipat Writers' Collective. He can be contacted at dpwriters@ drishtipat.org.

|