Inside

|

A New Dhaka is Possible Kazi Khaleed Ashraf outlines a plan for a modern dynamic Dhaka in the not too distant future Once upon a time, Dhaka was a very fine city. There were shaded and leafy streets, boats plied in the heart of the city, the air was cleaner, there was a sense of community among its citizens, people promenaded on the banks of the river, children played on open fields, until all those were usurped by the fangs of merciless urbanisation. Dhaka is now marked more by a frenzied economic engine and a lopsided sense of its future. What is touted as "growth" in Dhaka is actually the pillaging of the city in the name of planning and development. The end result is the same as elsewhere where the city is left to such pillage: curse of pollution, widening social inequality, increasing break-down of community, wretched transport and road system, blatant occupation of land and waterways, and ravaging of public spaces. No wonder Dhaka has acquired the dubious title of being one of the most "unliveable cities" of the world. Many modern cities have encountered pains of ruthless urbanisation, where development was not orchestrated by determined planning but by a combination of laissez-faire, ad-hoc, and pell-mell procedures. The city, in such a condition, practically becomes a hostage "in the hands of the mobs," as one writer was to comment on a major American city in the 19th century. The British writer Francis Trollope wrote about another American city from the same time: "Every bee in the hive is actively employed in the search for honey … neither art, science, learning, nor pleasure can seduce them from their pursuit." The city of possibilities slowly becomes a curse, a wretched place, when it succumbs to the relentless pursuit of monetary profits unless a combination of careful planning and civic commitment can turn that around. Dhaka is far from turning around; we are very much in the bowels of a disorder and don't quite know, besides some false promises and fake grandiosities, where to go with our city.

In the epoch of digital revolution and increased GDP, climate change and energy conservation, where is the vision for the city and its regions? Where is the place of cities in our national vision in the 21st century? We seem to be hop-stepping from one problem solving gesture to another: it is transport one day and housing another day, and then it is cleaning the river one moment and land-grabbers another moment. While all those enterprises are crucial, and we feel a little assured that some of those concerns are now part of a broader consciousness, the city is basically seen as a series of problems, and we are merely busy fixing them. We are basically proceeding without an understanding of the city as a civic, living experience. A good city is a civic organism. If piling buildings after buildings next to each other, on top of one another, does not make a city, what does? The term "city" itself derives from civitas, a Latin word with a cluster of meanings: citizen, civic, and civilisation. As the city draws people from various ethnic, racial, and social categories into one space, it becomes a place defined by differences and complexities. The most critical need for a city is a civilised means of addressing and sorting out these differences. The city ought to be a place where one may find one's personal and spiritual fulfillment in the company of others, uncoerced and in the light of human dignity. The ultimate expression of a well-formed civic place is the cosmopolis that becomes, in the view of the French philosopher Jacques Derrida, "a city of refuge," a place that guarantees anyone the right to residence and hospitality, and the opportunity for work, recreating and creative activity in a "durable network of fulfillment." How is Dhaka's civility failing? First, there appears to be no coherent vision for addressing Dhaka's current fractures and impending futures. What passes for a master plan is a jumble of outdated and uninspiring zoning regulations and building by-laws. The destiny of the city has been given over to bursts of ad-hoc and uncoordinated decisions. There is simply nothing in place that guarantees the art, science, and business of city-building. Second, the institutions entrusted with the planning and management of Dhaka have amplified the crisis. This is Dhaka's dreadful fate. The city's biggest nemesis are those who are entrusted with our destiny. With failures in urban planning and management, development in the last twenty years or so have fallen largely to private interests, which often act without regard to natural processes and resources, urban context, or social obligations. Third, one can vandalise a city by building it. The very process of building and developing a city, if not undertaken with knowledge of urbanism, can destroy the qualities that are at the heart of urban life. Every day the people of Dhaka negotiate increasing signs of a civic deterioration that is, ironically, amplified in the name of building, development and progress. Fourth, Dhaka is a traffic catastrophe, a narrative that needs no repeating. The street has become a circus that vividly depicts our general social behaviour: self-centred, undisciplined, and life-threatening to others. Fifth, Dhaka's environmental pollution is calamitous. There are factories in the city, brick kilns in paddy fields, and automobile exhaust everywhere, and yet Dhaka's citizens and authorities carry on with nonchalance -- economic interests dominate life and well-being. Sixth, open spaces -- urban spaces, water bodies, parks -- are the most important ingredients of a city, like lungs to the body, and yet they are vanishing one by one in an avalanche of greed and manipulation by private interests often in partnership with the authorities. A city is more than simply the dreary setting for minimal economic subsistence; it should be a place of inspiration catering to the mental and spiritual well-being of its citizens. Why shouldn't such notions as imagination, inspiration, and creativity be enshrined in the by-laws of the Master Plan? Yes, indeed, why shouldn't Dhaka be a "eutopia," a "good place"? Planning A New Dhaka But enough of capitulation to crisis when a new Dhaka is possible. We should instead talk uninhibitedly about forging a national consensus for a new plan for Dhaka and its regions. I believe with bold and innovative plans, informed by social, ecological and economic parameters, and propelled by political and legislative will, it is possible not only to transform Dhaka but make it a model of a tropical modern city. Like the urban wizard Jaime Lerner (who as mayor to the Brazilian city of Curitiba transformed it from desolation to a dynamic place), I believe that cities are not problems, they are solutions. We are now at a critical junction in Dhaka's progression when there is a fortunate conjunction of government initiatives and civic and media activism that call for an action to transform Dhaka. This is the big picture: If we can figure out how to transform Dhaka, we can do the same for the rest of the country. In the absence of a solid tradition of a civic, urban culture, Dhaka is the sole model, the city par excellence of the country. It is ironic that every small town, every nook and corner of the country mimics the dysfunctional Dhaka in one form or another. It's not too much to declare that the future of the nation depends on how we plan Dhaka city. I am an advocate for a civic, dynamic and hydrological Dhaka. Far from being condemned to be a calamity, Dhaka can become a Bengali city, a tropical model that responds to the unique geological and environmental conditions of a deltaic place. Even until the 1950s, with its spacious green spaces, majestic trees, crisscrossing canals, civilized riverbanks, and boats plying in the city, Dhaka promised to be both a garden city and a place by the water. With buildings in a setting of lakes, gardens, orchards, and parks, Dhaka can still set the model for a tropical city in the twenty-first century. A well-functioning city has both poetry and pragmatism. Such a city is designed and meticulously planned which is then diligently implemented; there simply is no short-cut from that. While there should always be latitudes in design, a city begins and proceeds with a plan, one that has both poetic vision and pragmatic arrangements. Dhaka needs a vision of what it can be, what is possible, and what is profitable in the most collective sense. Development and investment should follow that vision. And the plan should be based on the art of "urbanism," on the quality of civic culture, and not the technocracy of urbanisation, a set of abstract statistics and economic chart. When it comes to cities, two plus two is not four. Although there are lots of activism around human rights issue, women's issues, and some around environmental issues, there is no organised activity around the future of the city, to imagine changes, and to demand such changes at a popular or community level. To bring changes to a city like Dhaka, we need political will, bold imagination, and a serious commitment to carry that out. The planning of Dhaka needs imagination more than technocracy. Dhaka needs more imaginative prowess than, say, New York City. People who understand the designing of cities should be brought to the helm and not bureaucrats and seemingly uninformed technocrats. What follows is an inventory of some old and new realisations for a new start for Dhaka: A Liquid Landscape

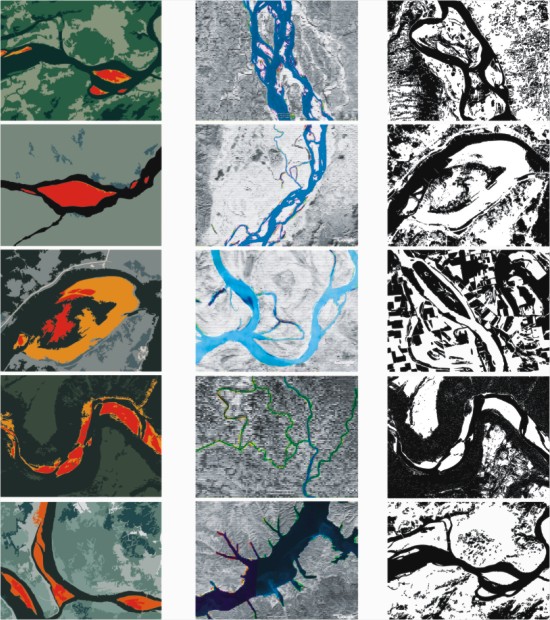

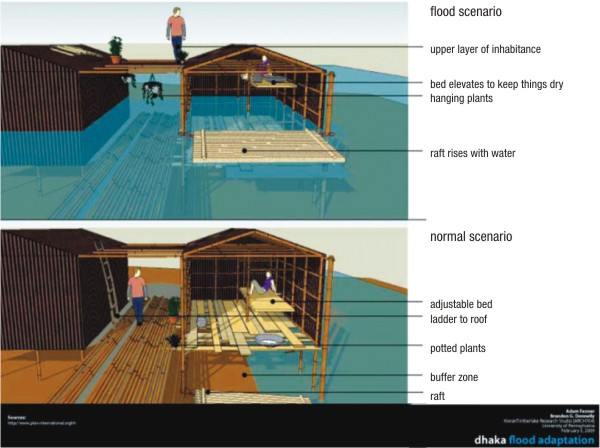

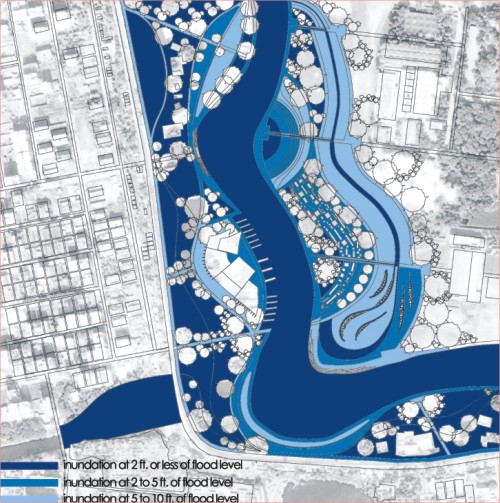

Dhaka was a deltaic city; water in the form of rivers, canals, waterways, ponds and flood plains formed the matrix of Dhaka. It is not just an image of a picturesque landscape, it implies communication, drainage, economic life, festivity, and a certain way of being. That's what made the city unique, which required a different strategy for urban development and planning. But since the 1950s all that has been destroyed, either systematically or as the fall-out of one misplaced decision after another. Embracing water and wetness is a natural consequence of this landscape. Planning around land and water (and not land versus water) could give Dhaka a very unique feature distinguishing it from the other cities of the world. As co-writer and architect Saif Ul Haque notes: "Water could provide inexpensive transport solution for the city, it could serve as reservoirs for containing monsoon rains, it could provide for valuable protein for the city dwellers by fish farming, and it could help in keeping the underground water table stable by way of percolation and other induced methods." The most crucial point of start is to realise where Dhaka is. Too few planners, far less city fathers, and even the people of the city recognise that Dhaka is a tender land-mass -- virtually an island -- framed by three rivers and a fluid landscape. Dhaka cannot forget its genealogy, for that forgetfulness will be reciprocated by calamities and various dreadful environmental effects. A ten-minute ride outside Dhaka shows the aquatic reality of the land-flood plains, wetlands, agricultural fields and canals completely girdle the city. The whole of the Bengal delta, in fact, is an amazing chemistry of land and water, where mighty rivers churn through a landscape characterised by rainfalls, cyclones, floods, and silting of monumental proportions. Dhaka experiences nearly eighty inches of rainfall per year; sometimes over five inches of rain will fall in a single day, turning the city into an unscheduled Venice. In such a fluctuating landscape where the edge between land and water, between settlement and landscape is often blurred: What should be the perimeter of the city? What will happen at that edge? How will the two sides of this fluid edge be planned? Dhaka cannot grow infinitely in every other direction, swallowing up wetlands and agricultural land with mind-numbing speed and greed, and throwing off balance a precious ecological and hydrological system. If not, then, how will be the population growth and the appetite for urban land solved? That is the challenge. The brilliance for urban designers and planners will be to show growth can be addressed by sustaining and enhancing Dhaka's crucial geographic system. The norm of thinking about Dhaka has been to think from the core -- the built city -- but that has to be reversed. An audacious vision for Dhaka has to begin from the edge of the precious landscape of wetlands and agricultural terrain, ushering a conception of a city that integrates urbanism, agriculture, and flood. The big point is: You can try to take the city out of the delta, but you cannot take the delta out of the city.

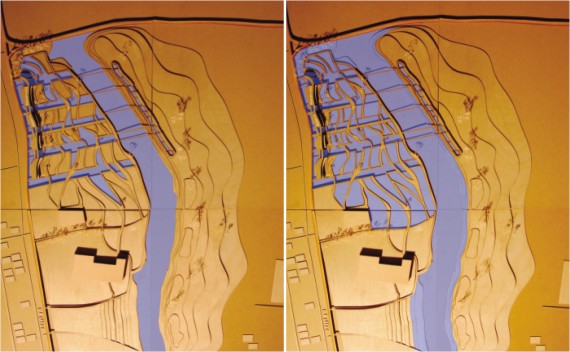

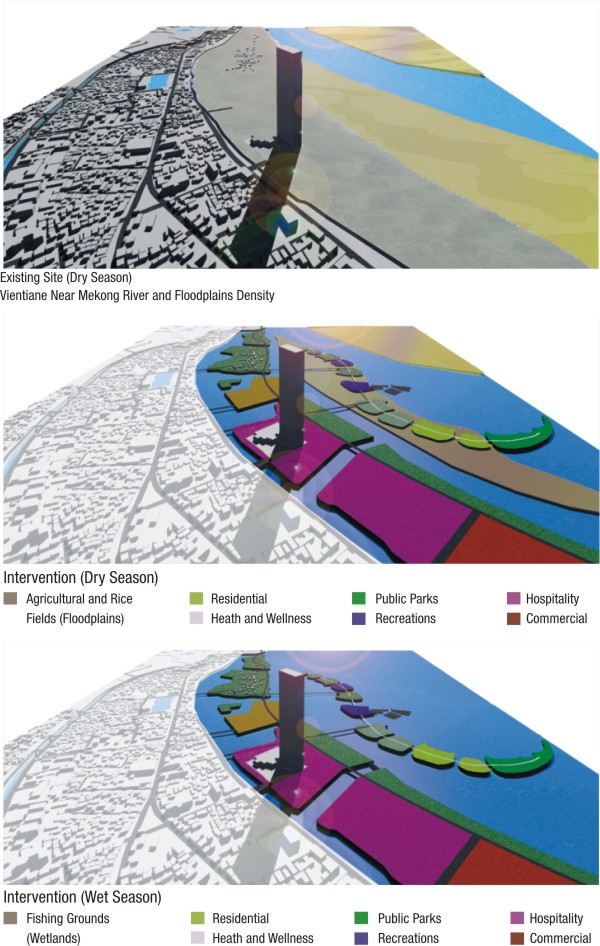

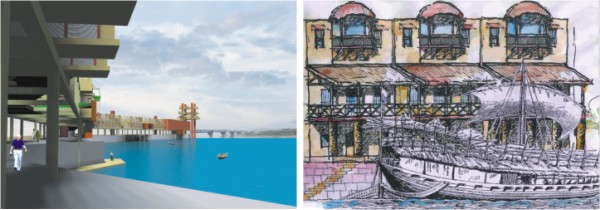

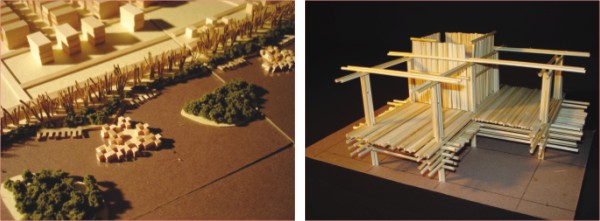

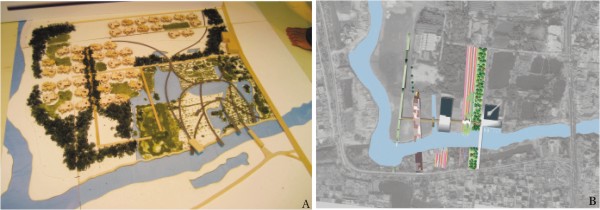

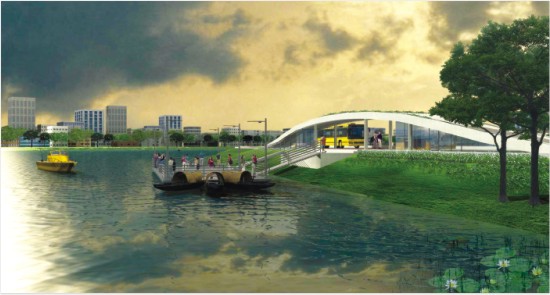

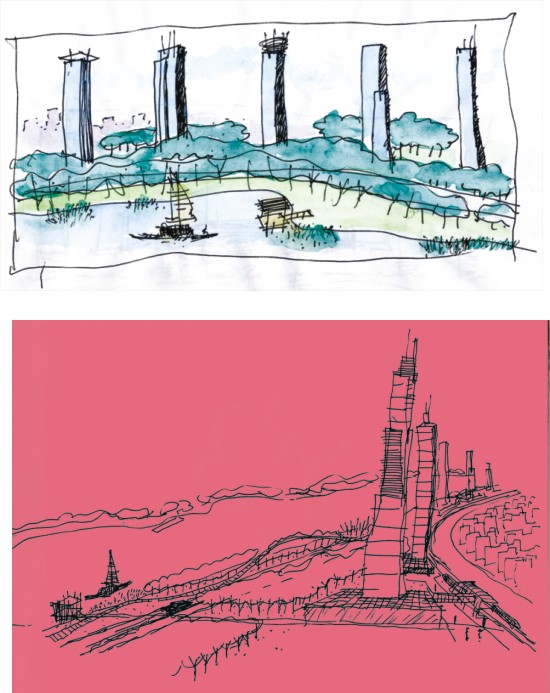

A proposal for Vientiane on the Mekong River (Siphathay Phanphengdy, University of Hawaii, 2010).

Dhaka is a child of the Buriganga, and yet it turns its back to the fundamental reality of being part of the world's most dynamic hydrological system. A radical reclamation of Buriganga river and its banks on both sides is crucial for an economic, transport and cultural reinvigoration of Dhaka. The river can become a sustainable life-blood, and the riverfront a much more organised area providing renewed recreational, civic, economic, and transport facilities for the whole city in a way never witnessed before (the present government has already initiated strong steps in that direction, those should be linked to a larger plan for the city). Working with the river means working with a total environmental relationship. The rivers, the wetlands, the flood plains, the eighty inches of rain per year, the drainage are all tied in an intricate relationship. Make malls if you will, but do not forget the wind and the rain. Dhaka is a deltaic city; it cannot be developed by standard economic intentions alone. Instead of being fated as a third-world reality, Dhaka can be a very special city, a place by the river that works with water and vegetation to be a truly tropical city, and one that is economically and ecologically sustainable. Working with its geography and hydrology, and its growing urban needs, Dhaka can still be a very unique, green and highly liveable city. Far from being what it is now, Dhaka can become a tropical model that responds to the unique geological and environmental conditions of a deltaic place, a new paradigm for city, landscape and community.

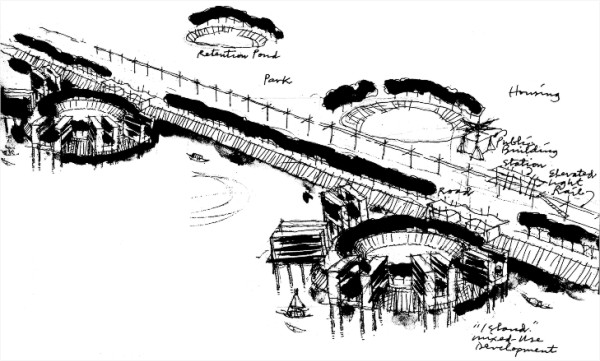

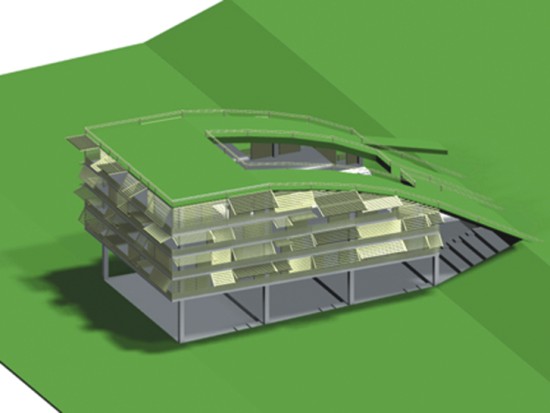

Disperse Dhaka, Contain Dhaka It is not a contradiction to say disperse the existing city, while at the same time contain its unhinged enlargement. Dhaka is "growing" in its own happy rhythm, tickled every now and then by some half-baked official initiatives. This "growth" is neither relieving pressures at the centres nor creating a liveable urban development. The whole city and its peripheries should be brought under an active and aggressive planning net and coordinated development spurs created. New urban nodes as townships should be created, and certain existing nodes revitalized so that selective commerce, institutions, and government offices may be dispersed across the region in a coherent and planned way. Dhaka can be both a garden city and a water city, a network of planned settlements amidst an aquatic, productive landscape. The old "garden city" idea of the British planner Ebenezer Howard with his declaration that "town and country must be married, and out of this joyous union will spring a new hope, a new life, a new civilisation," can be revisited with new energy and innovation in the context of Dhaka. The idea needs an imaginative interpretation where nodes of development can be created in thoughtfully designated locations surrounded by green and aquatic spaces in order to move industry and population out of the crowded centers to planned peripheries. Once the footprint of the expanded city is identified based on a balance of ecological imperatives and human settlement, the perimeter should be carefully delineated so as not to affect more agricultural areas and wetlands. A rigorous balance should be established between Dhaka's urbanisation needs and ecological obligations. As new nodes and foci are created, existing ones should be revitalized, especially those that are along development corridors but suffering from mal- or non-planning. A dispersed city will rely on an efficient public transportation system based on a combination of light rail transit, extensive buses, and riverway ferries and taxis. The spread and expansion of Dhaka will succeed based on how its various parts are connected.

Revitalising Existing Nodes: Tongi

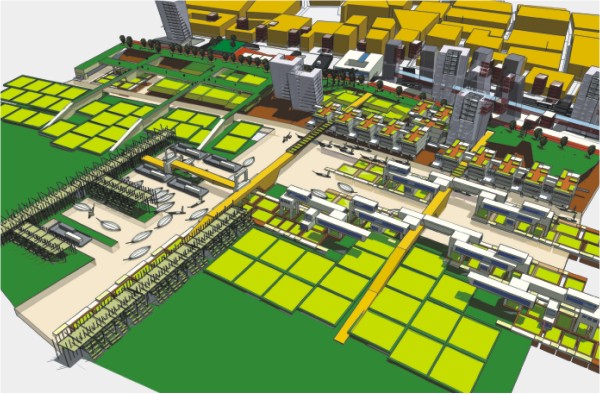

Most of Tongi is either ill-developed or underdeveloped, and basically no better than an elaborate bazaar, but the irony is that it can be built as a planned town with efficient use of its land and property. The Tongi bridge area, instead of being a shoddy ensemble of shacks, latrines, and ditches can be a more economically and culturally vibrant riverfront and an endearing entrance to Dhaka city. Tongi can become the model of an "eco-city" that maintains a balanced relationship of development and ecology, maintenance and use of river. The area close to the bridge, along the banks of the Turag, can be developed as an arts district. The proposed plans here show the area west of the bridge as a combination of reconstructed wetlands, parks, housing and pedestrian spines. The second plan shows a series of civic spines that register the flood-water in different ways. Each spine is dedicated to particular public purpose: from flower fields and orchards, to theater buildings and recreational platforms. Rejuvenating Existing City: Sadarghat Riverfront Development

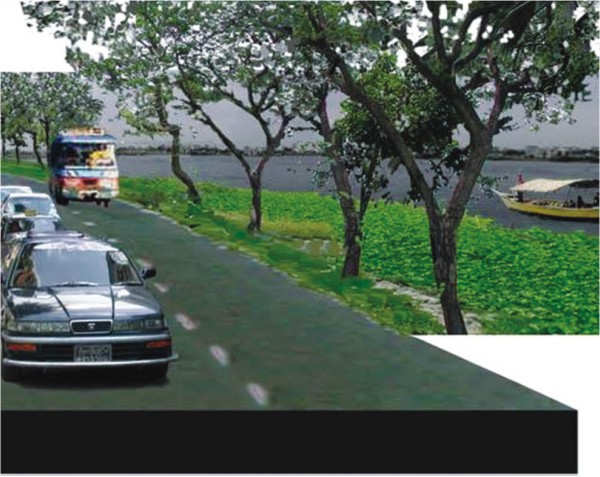

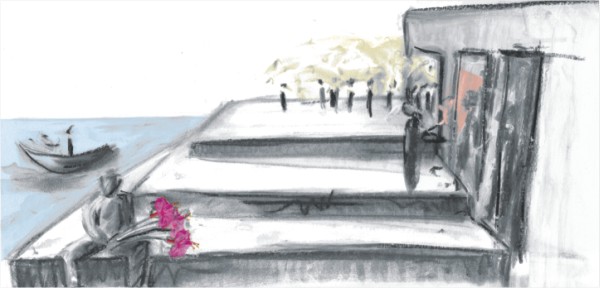

Sadarghat remains one of the most dynamic areas in Dhaka, but its fullest potential has not yet been realised. A Sadarghat Riverfront Development could be a catalyst for an economic and social rejuvenation of not just old Dhaka but the whole city: A "riverfront district" with Sadarghat as the epicentre for the purpose of producing and maintaining a clean river, a decent riverfront and a sustainable and exemplary riverfront district enjoyable and accessible to everyone. The principal and single-minded aim of the enterprise would be to bring the people to the riverbanks. The whole length of the riverbank in the district should be developed as a tree-shaded promenade, largely a pedestrian public space that is linked to other open and green spaces, parks and gardens, historic sites, and especially designed buildings for special purposes creating a clear and legible pedestrian network. Innovative building types will have to be conceived that conform to the river and canal-front conditions. A re-planned and reconstituted Sadarghat can be a more powerful economic engine than the ramshackle bazaar and ad hoc economy it thrives on now.

A City Thrives on Efficient Mobility

It is no new news that traffic is Dhaka's Achilles heel. Unless the transportation system is organised, Dhaka can never function either as a globally-positioned or a cosmopolitan urban place. But there is no short cut for transportation problems no matter how much hue and cry is raised every day, and no matter how many magical solutions and "fixes" are flaunted. Transportation ideas are tied with the overall plan of the city. No vision, no solution. A modern city thrives on efficient mobility and interconnectedness. A plan for Dhaka has to be regional in scope that links towns and centers in a hierarchic orbit of links and connections made possible by multi-system transportation. A plan for new nodes and consolidating existing ones with the intention of de-congesting the cores is dependent on an efficient transportation. Similarly, transportation plan must be predicated on effecting long range development goals. Such a plan should not be merely "fixing" problems but generate new quadrants of urban communities. The only solution to Dhaka's transportation madness is simply mass transit, that is, various forms of transportation that carries large number of people in an organised fashion. The systems can be train, buses and water-based vehicles. As long transportation is reliant on smaller and private vehicles or some buses, the curse will not go away. A multiple system of trains need to be considered, from fast, regional commuter trains that connect Dhaka and its far regions such as Mymensingh and Comilla (a consequence of this would be a re-planning and growth spur for some of these orbital towns … if I can arrive in Dhaka in one hour from say Mymensingh why should I live in Dhaka). Another slower moving transit system can be developed that connects the immediate regions of Dhaka. The existing north-south railway track could be revamped for a faster regional train linking Gazipur to Naryanganj. There could be two train stations for a city as vast as Dhaka. Tongi Station could be developed as a major hub for trains going north, while Kamlapur could serve the southern and eastern parts. While long-range trains can stay on existing tracks in that north-south corridor, an elevated track may be built over the existing track for light rail connecting city areas. The roads are a particular absurdity of Dhaka. The same surface of roads that existed in the 1960s is servicing Dhaka now while traffic volume has increased twenty-fold. The city of (Airport Road and Mirpur Road) running north and south along the axis of the city's develop ment [cantonment]. And there is nothing.

The east-west connections are nominal, and north of Bijoy Sarani there is no connection at all until you reach Ashulia. A circular highway can be developed ringing the city along the river embankment which will carry heavy and faster traffic, including city buses. Cross roads may connect the circular highway through the city. Intersecting nodes of roads and train lines can facilitate transfer. Elevated roads and flyovers are follies for they solve nothing other than stand as monuments to a false modernisation at the expense of disrupting the social and physical fabric of the city (they were invented for the American highway system privileging the uninterrupted movement of the individual cars). On top of that, they neither support mass transit nor connect efficiently with intermediate spaces (there will be clogging where you want to get off or get on from such a location).

What about a water bus system circling the city, following the natural course of rivers framing Dhaka? Water based mass transit is being approached too slowly when that could be effective more immediately as it does not require extensive infrastructure as roads or rails other than stations and link/exchange to road transport. The circular waterway can similarly connect with major transfer nodes for other modes of communication.

Make Dhaka a Walking City The sidewalk (or the footpath) is the mark of a city's civility; it belongs to the culture of walking, strolling and promenading. The quality of sidewalks gives evidence to what the city managers think about a fundamental human condition: the pedestrian and his humanity. Dhaka shows no such conceptions. It's a city where driving a car has become an essential symbol, and the poor pedestrian just a pitiable creature at the bottom of the totem-pole (consider the unfortunate and tragic deaths that happen with predictable pattern). Such urban pedestrian devices as boulevards, promenades, river-walks, just simple sidewalks with various activities that are the hall mark of all livable cities are completely non-existent in Dhaka. The infrastructure for walking needs radical overhauling. A sidewalk is not the extension of a drain, nor is it a three feet wide cover over it; it is a space by itself, it is a linear civic space and a network of movement. It need not be a concrete cover always. It can have many material variations; it can be overgrown with grass to reduce heat gain. It can have canopies or be covered (as many footpaths in Kolkata have). Sometimes it can be broad enough to be an urban place with small gardens, benches to sit upon, with urban activities such as a café and newspaper stand. In many cities, a whole automobile street is pedestrianised for certain part of the day or week on a regular basis. A sidewalk in Dhaka will continue to be used for multiple reasons especially for portable commerce and as sleeping areas for many at night, still a sidewalk culture should be developed and maintained by proper regulations that embraces both the pleasure of walking and social interaction as well as the commerce of vendors. The pedestrian and the sidewalk is ultimately an indictment on the car, on its ultimate effect on the natural environment (through pollution, etc.), urban exchange (disintegration of the public realm), and social interaction (segregation of classes). Wealth and automobile do not have to go hand in hand. Hong Kong is a good example where an integrated planning approach has succeeded in maintaining low automobile dependency despite Hong Kong's high per capita income and population density.

The success of Hong Kong's pedestriani-sation was possible due to the integrated network of pathways that separate car and pedestrian, and allow those pathways and sidewalks to be spaces of their own. A successful pedestrian infrastructure means relying mostly on a set of public transportation such as railways, buses, vans, trams, ferries, and such public spaces as elevated and moving walkways, tunnels, footbridges and regular sidewalks. Planned Housing and Designed Settlements

The quality of life in a modern city is ultimately about the patterns and conditions of housing, and not its dazzling monuments and fanciful institutions. Housing is no mere building volume nor it is merely numerical and fiscal matter. One good individual house multiplied by 1,000 does not make for a good housing. Housing is the site of interaction between building, individual and community. Housing is the key factor influencing the quality of human life; it can give one despair or hope, as many have noted. Housing will continue to be the most critical issue in a city that is destined to be the densest place on earth. And yet housing is Dhaka's greatest disappointment. There are no suitable models for housing for the many different communities that inhabit Dhaka city, and no examples of housing patterns working civic and ecological priorities. The public sector housing, catering to government and corporation employees still continues along the defunct idea of building one block after another with no thought for in-between spaces. The limited and lower income groups have been completely ignored in the housing equation. The middle-class is living by making do what it can in the brutal housing and rental market.

The planners and experts are still floundering with two dull-witted models: the individual plot with the independent bungalow-style house, and the individual plot with a clunky apartment building. None of the two are effective in creating the fabric of a cohesive community with an admirable quality of life with the density of the city. Planners and developers should realise that taking up land, worst still taking up low-lying lands, simply filling them up, running street grids, making plots and selling them do not make for planned housing. It is, at best, scheming and plotting. The unimaginative strategy of making "new" housing areas by plotting and subdividing land should cease immediately, and alternative imaginative models of mass housing explored. (Notice what happened to the original form of Dhanmandi, Banani and Gulshan, where the idea of the "bungalow in the independent plot" gave away to a denser building type creating a totally new urban layer).

There are many possibilities. Instead of building up on a plot in an isolated manner, what about pooling 8 to 10 plots together to develop one single housing complex with various internal facilities including meeting areas and generous open spaces, a shop or two, play areas, or gardens for the whole complex? Loan and tax incentives may be offered for initiating projects like this in existing built conditions such as Dhanmandi and Banani. For newer areas under planning, such group housing should be introduced by regulation. For heaven's sake, please stop the same pattern of plot-making in Uttara, Purbachal and other so-called planned towns, and develop newer housing types with greater density and better civic life. For upcoming projects, creative economic partnerships may be offered. Government land may be given to developers for large-scale development but certain percentage in the area/volume in the development should be built for low-income/middle-income occupation.

Building Communities

Housing is the fabric of the city that creates the social nucleus called a community. The pattern of housing and its components, and how they are arranged, can enhance the quality of life, both the life of the immediate dwellers and the life of the city. Nurturing the nature of communities, the social nucleus in which we dwell, make our lives supportive and meaningful. The opposite could be true too: Ineffective patterns can disrupt the structure of communities. Housing is a verb, so said the housing guru John Turner, implying that housing is not simply shelter but what we do. As many have cited that most settlements are not an abstraction but an architectural expression of a social reality, the way people relate to one another. The patterns of settlements reflect human bondings and community spirit; they can foster families and their ties to other human beings. Once upon a time, we had a word for community -- moholla -- which is slowly disappearing from our consciousness. Dhaka has become a city of fragments, with its social cohesiveness tattering away, broken down to the individual households living in their walled enclaves. Notice how the biggest investment in the city is walls and fences, none of which fare in our rural dwellings ... so much for civic polity! The truth is that the general form of a city -- its physical and spatial pattern -- is capable of nurturing or disrupting the nature of communities. This is critical in the context of Dhaka today when older patterns of communities are fast disappearing, and the current pattern of buildings hardly encourages community building. Stunning buildings with glorious names like "Dreamland," "Green Paradise," or some such things do not make a community. On top of that, incalculable psychological anxieties and pathologies are generated from current architectural models. A nurturing community requires planned and designated spaces for healthy social interactions at many levels, for children to older people. The spaces can be courtyards, gardens, parks, community gardens, playgrounds, coffee shops, or various kinds of community spaces appropriate for that community. There should also be designed hierarchies of spaces, from the intimate to the semi-public to spaces that link with larger urban system, each one catering to different community needs. Urban Catalysts

Large-scale building projects and urban design interventions have often been an occasion for catalytic event to give new cultural and economic impetus to a city. What was once a depreciating and dreary urban environment has often been turned around at the physical, psychological and economical level by the creation of a new and inspiring works of architecture. Such is the power of good architecture and urban design, a single act can change the life of a city. The purpose and effect of architecture are manifold, some are immediate such as the function it is built for, and some are far-extending such as the emotional impact it might have on a larger populace. Even as a single building, architecture is not an isolated phenomenon. It affects its surroundings and continues to having an impact for a long time. The power of catalytic architecture must be identified as also when and where it is needed. To recognise and initiate that also needs wisdom and daring. If the Assembly Complex at Sherebanglanagar was a spark produced in the 1960s by Louis Kahn, Dhaka needs such impetuses. There are some critical areas in the city that can be addressed in the most creative way before they are vandalised by illegal invasions or poor official planning. Such areas should be developed in an exemplary way to inspire and edify people, as well as open them up for new experiences. The old airport area is waiting patiently to be used as a new talisman for the city (until that happens we do not understand why that area cannot be enjoyed temporarily as a public park, and we are mystified as to why an ugly wall has to be put up around the area).

The central jail could be relocated at a new location and the area opened up for new cultural, recreational and selective residential uses for the people of old Dhaka. If nothing else, the area can become a lung-like “Central Park” for that part of the city. Peelkhana could similarly be renovated and reused. Also: Taking any of these areas -- the old airport, Peelkhana or the tanneries -- invite ten top architects of the world to provide their visions for Dhaka for that site, and perhaps implement one of the ideas. Even if the process costs a bit, it is nothing compared to what priceless gift it will bear for the future of the city, towards its dynamic transformation. Hatirjheel New Urban District

Open Spaces for the Sake of Life

Open spaces are one of the most important ingredients of a city. Buildings alone never make a city, but buildings and spaces in a well-knit fabric. The spaces -- lungs -- are wide-ranging, from formal to informal, from large-scale to intimate, from paved to green. Large spaces include large areas of assembly, maidans, parks, gardens, lakefronts, riverfronts, etc, while small spaces may just be an intersection of two lanes, space under a tree on a sidewalk, or just a broad sidewalk. Dhaka has the fortune of riverbanks that are a natural treasure of potential public spaces (that is, if they can all be recovered and planned accordingly). Dhaka one time had an enviable resource of enjoyable spaces; now they have either vanished or are vanishing in an avalanche of greed and manipulation. Dhaka was, and is no longer, but again can be a place of light, green, and air. An immediate and water-tight moratorium should be set on all construction activities in open spaces. And spaces that have been brutally violated should be recovered without mercy. How priceless such spaces, more valuable than a building with Taka 3,000 per square feet! How ironic that we build and build, we fill up lakes and open fields and build, and then we pay a hefty price to get a lakeside view (if the lake exists any more after the development fury)! And we give those buildings ironic names: Lakeview, Gardenia, Wisteria.

How absurd that we make a world-class public space as South Plaza (in Sherebanglanagar), and then shut it off for some paltry reason of security! South Plaza belongs to the people and not to some phantom miscreants, and it should be returned to the people (security can be organised in many other ways). The proper image of a city is given by all those things in public spaces that add up to the total urban environment -- benches, sculptures, fences, light-posts, signages, fountains, billboards, bus stands, newspaper stands, the whole paraphernalia that falls under "urban art." Every little thing matters. And being a poor country who shouldn't we be concerned about that? Why should we allow a ramshackle newsstand on the sidewalk? Why should we let a horribly designed fountain pass as urban art? Why should a shoddy police box stand in my way of walking? An Urban Arts Commission formed by members seriously committed to the love of Dhaka and knows the art of urbanism should be entrusted to monitor such images for the city. The city of Dhaka used to be synonymous with trees -- flower-bearing, scent-emanating trees, trees that marked the passing of the seasons (even a densified city as Tokyo gets magically transformed during the cherry blossom season). A model in the mind is the street in front of Dhaka Medical College, or what it used to be, a most dignified row of shadow-giving, corridor-creating trees, or a street intersection in Becharam Dewry with a banyan tree creating a cool space-defining public square. But that was then, when we were a bit more civic-minded, and concerned about the larger scheme of things. Now we have simply become urban bandits, pillaging and raping all things good about the city. Dhaka could have been a garden city, where the rush to build did not stop the civilised and healthy need for trees and vegetation at every available nook and corner of the city, where buildings could be seen as pavilions in a garden. The climate of Dhaka desires it to be a garden city.

There are indeed many Dhakas in this city. Dhaka has given rise to several urban morphologies, each of which represents a particular social, economic, and environmental destiny. In the older city, hugging the river, colourful mixed-use buildings are crowded cheek-by-jowl along narrow, winding streets in neighborhoods that are still traditionally organised. Further from the river in the Ramna area is the old colonial quarter, studded with bungalow-and-garden type governmental, cultural and residential buildings, many of which were built during the colonial rule. Louis Kahn's Parliamentary Complex is another distinctive area of the city's urban and social fabric. The so-called planned residential areas created as plotted properties with individual buildings were the most distinctive development of the 1960s and later, but interestingly that morphology is being deformed completely. Alongside these formal areas, however, are vast, amorphous swaths of largely unplanned residential and commercial growth lacking adequate infrastructure that are glaring symptoms of planning failure in addressing the rapid transformation of the city. It is a fact that a vast population of Dhaka remains untouched by the promises of urbanity.

It would be a pity if all of Dhaka began to look the same, which is what is beginning to happen because of uniform development orientations. Certain areas in the city -- "urban treasures" or heritage-rich places -- should be immediately marked as special zones, and every means should be adopted with the utmost urgency to preserve them through regulations. There are also heritage-rich areas like Ramna, Wari, Chowk, etc. Part of Ramna with some of the colonial era buildings should be converted into a museum district. And there are pockets of urban assets, those that offer unique opportunities in the experience of the city such as Balda Garden as an edifying garden, Shakhari Bazar as a heritage place, Mirpur Botanical Garden as a recreational landscape, and various historical sites. There are also many unrecognised areas that no longer come under the urban radar but which should be designated as assets and restored, such as Ali Mia's Talao, Armenitola Maidan, to name a few. Kazi Khaleed Ashraf is an urbanist, architect, and writer, and teaches at the University of Hawaii. Ashraf's writings on the urban future of Dhaka, including sections of this article, appeared in The Daily Star and FORUM since 1996, which have occasionally been co-authored with architect Saif Ul Haque.

|

||||||||||||||||||||