Inside

|

In the Footsteps of Atisha:

A journey into modern Tibet

SAMIER MANSUR experiences not enlightenment, but a betterunderstanding of the ever-changing world, in Tibet.

Nearly one thousand years ago the reputed Atisha Dipankara, a Buddhist scholar of royal birth from the town of Bikrampur (now Dhaka district) made the hazardous journey into the Land of Snow at the invitation of the Tibetan king. There, the Bengali achieved tremendous success in revitalising the Buddhist teachings after its decline and suppression in the region -- a task for which he was, and continues to be recognised as a Bodhisattva, an enlightened being.

|

PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES |

After learning of Atisha's remarkable story, coupled with inspiration garnered from watching Brad Pitt's blockbuster hit, Seven Years in Tibet, I was pretty well convinced that a trip to Tibet included in the steep price of transportation, lodging and local guides, the opportunity to have my inner-Buddha flower. But alas, this did not happen. Perhaps it was my false expectations, or the daily snow showers and frigid temperatures that prevented such flowering -- but whatever my excuse for not returning an enlightened Bodhisattva, I'm not quite rushing to get my refund, either.

For many, including my pre-Tibet self, idealisations of the Himalayan kingdom are largely based upon fantasy. Propelled by popular culture and the mythical search for the last Shangri-La, the final bastion of spiritual utopia on Earth, the romance of Tibet, is chimera, an emotional construct of necessity. We need to believe a place on Earth exists in which peace and incorruptibility reign supreme, where the beauty of a land and its culture triumphs over some of the painful realties that life sometimes doles out. As much as I had hoped to encounter such a place, this was not the Tibet I experienced this past spring when my travel companion and I spent eight days driving across the Tibetan Plateau from Lhasa to Kathmandu.

It was clear from the beginning that a trip Tibet would be one unlike any other. Our travel agent in Nepal began by listing a litany of unpardonable faux pas: do not talk about politics -- especially not with monks, some of them are known to be Chinese agents; do not wear, carry, or show any image of the Tibetan flag; do not carry books that speak of or depict the Dalai Lama -- any of these infractions is grounds for immediate deportation.

He concluded, “Do not expect much from the hotels, they are almost okay.”

We had been warned; and with these warnings, we landed at the surprisingly modern Lhasa Gong Ga Airport after a breathtaking flight across the Himalayas, which skirted by Mount Everest and soared over the Tibetan Plateau. It was our drive from the airport to the capital city of Lhasa that revealed some of the many paradoxes that make up modern-day Tibet; powerful images and experiences served as a constant reminder of Tibet's ever-changing landscape.

We stared in awe out the window at the bluest skies, the towering snow-capped mountains of a thousand shades of browns, blues, greys and whites, and the picturesque homes that stood ornately alongside the freshly paved and wide-laned highway we were driving along. “This is a land that would inspire poets!” I revelled. Revelries which our proud Tibetan guide, Ringpun, interrupted as he pointed out, “The Chinese government makes sure these houses are well decorated and furnished on the outside, but this is not typical of the way most Tibetans live.” As for the tunnel we were entering -- a tunnel carved into the mountainside that saves commuters two-hours en rout to Lhasa, a tunnel which, I should add, as far as aesthetics goes, would be the envy of any developed nation -- Ringpun added, “the Chinese build these roads and tunnels one year, and then spend the following years repairing them as they break apart.” All these symbols of modernity and prosperity that I was delighting in, he insinuated, were a mere façade, a reckless attempt at development at best. Indeed, throughout the rest of our journey, four-hour hold-ups along the highway were routine when a segment of the road would cave in, causing vehicles to line up alongside the roads for as far as the eyes could make out.

PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES

PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES

It was fast apparent that Tibet was a land under construction. Every building passed on the road to the capital looked as if it was plastered and painted that very day. And for each freshly erected super mall, government office, international car dealership, bank and other symbols of globalisation and development, there were three others at various stages of completion. In Shigatse, Tibet's second largest city, for example, entire streets were closed off with each block lined and covered in green-netted construction scaffoldings. According to Ringpun, these buildings were built only two years prior, but recently began to crumble due to cheap construction and negligent building codes; hence the re-construction of the city.

For all these infrastructure issues, however, Lhasa seemed to be an exception with its solid, historic foundations surrounded by a bustling, modern city-centre.

The capital has built up through the ages around two of Tibet's most honoured and sacred sites -- the 7th century CE Jokhang Monastery, built by the founder of the Tibetan Empire, Songtsan Gampo and the sprawling Potala Palace, home of the Dalai Lama. In front of Jokhang Monastery, considered by Tibetans as the Holy of Holies, is Barkhor Square, which has served over the last few

decades as the symbolic centre of protest against Chinese occupation. Today, the square is lined with market stalls hawking everything from religious motifs and souvenirs, to pots and pans, produce and baked goods. High-end designer stores and restaurants form a ring around the plaza, where one can delight in various dining options from traditional Tibetan cuisine to Tibetan fast-food chains with Yak burgers and Continental fare, to Italian Espresso bars with high-speed, Wi-Fi internet access. Pilgrims and tourists from around he world fill this bustling space to circumambulate the Temple premises, shop and enjoy a hot meal surrounded by the majestic mountain scenery in the distance; all the while heavily armoured soldiers march up and down the square in squads of four, making their presence known.

It was on day two that I experienced the famed Potala Palace; it would be my first glimpse of the state of religion and spirituality in Tibet. Built in the 17th century as the royal residence, seat of religion and house of government, the grand palace is built upon a hill, flanked on either side by the Himalayan range as it overlooks the capital city. After climbing the 432 steps to reach the entrance, we were given a time limit of one hour to explore the thousand-roomed palace. Inside was a maze of chambers and ornately decorated rooms lavishly painted in colours of red, blue, green, yellow and white -- representing the balance of the five earth elements. Colossal Buddha statues and those of Tibetan Buddhist leaders lined the interior halls while imposing stupas adorned with precious stones, weighting tons in pure gold, chronicled the history of the Tibetan Empire.

PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES

PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES

Despite the grandiose exterior and priceless artefacts that filled the palace, I found the place to be dark and cavernous, weighed down by the heavy decoration of religious artefacts and motifs from antiquity. In fact, this was my perception of most of the monasteries we visited on our drive through the plateau. They were dark, cavernous and cold. Their walls, blackened by the soot of centuries of burning butter-fat candles.

When visiting the 9th Century Pelkor Chode Monastery in the city of Gyantse, halfway through our land journey, I wondered, “How can anyone achieve enlightenment in this cold, dark place?” Of course, “cold” and “dark” are relative terms when coming from the hot and sunny Bangladesh -- I was immediately repudiated for such unholy thoughts, for within a few moments, lightening stuck (within my stomach) and I found myself frantically searching for the loo! Whether it was my blaspheming, or the yak butter-milk tea I had earlier that morning, I learned a valuable lesson that day -- always carry extra toilet paper when travelling through remote mountain kingdoms where doorless stalls with holes in the ground are sufficient to earn the title of “Restroom”. Were it not for two Tibetan pilgrims with generous helpings of tissue paper who discerned the plight of desperation on my face reacting to the lack of toilet paper, this experience would have been far too traumatic to recount.

But I digress.

Tibet appeared to be a land caught between two extremes. In the monasteries I felt a clinging to the past. The foundations, walls and the peeling paint were, in most instances, centuries, if not over a millennia old. Once these grand monuments were thriving centres of intellectual activity and religious learning.

Today they are crumbling, desperate to remain relevant in a rapidly modernising society, while clinging to their original foundations.

Perhaps this is by design. One of the goals of the Cultural Revolution was to eradicate all vestiges of religion, which was deemed backwards and oppressive, an impediment to the utopian vision of the new People's Republic of China. A nationwide campaign was orchestrated under Mao Zedong's Red Guard to “cleanse” society of religious superstition, during which countless artefacts and religious texts were destroyed, thousands of Tibetan monks and clerics killed, tortured, or sent to camps and over 6,000 monasteries left smouldering in ruins. As recently as 2008, up to 200 protestors were killed in the aftermath of a violent crackdown by Chinese authorities, with thousands of others injured and imprisoned. To this day, reports of monks and nuns gone missing are all too frequent.

Perhaps this is by design. One of the goals of the Cultural Revolution was to eradicate all vestiges of religion, which was deemed backwards and oppressive, an impediment to the utopian vision of the new People's Republic of China. A nationwide campaign was orchestrated under Mao Zedong's Red Guard to “cleanse” society of religious superstition, during which countless artefacts and religious texts were destroyed, thousands of Tibetan monks and clerics killed, tortured, or sent to camps and over 6,000 monasteries left smouldering in ruins. As recently as 2008, up to 200 protestors were killed in the aftermath of a violent crackdown by Chinese authorities, with thousands of others injured and imprisoned. To this day, reports of monks and nuns gone missing are all too frequent.

Of course, we never saw nor heard any of this during our trip; it wasn't part of the official script. In fact, as we left Potala Palace, we inquired about the recently erected monument that stood directly in front. Ringpun observed it pitifully and responded, “That is to commemorate the peaceful liberation of Tibet.” He choked back laughter as he said the words “peaceful liberation” -- from that same spot 50 years ago, rocket shells were fired into the windows of the palace, which now waves from a mast above its central roof, the bright red flag of Communist China.

Outside the thick walls that divide the monastery interiors from the rest of Tibet, one gathers the impression that this is a land on the move; it is the emergence of a modern Tibet as envisioned and fashioned by China. The endless development of cities, highways, railways and constant flow of heavy mining machinery digging into the serene landscape are a testament to this and stand in stark contrast to the indigenous horse and mule transportation, and colourfully decorated yak ploughs which graze the countryside. Like the course of history and progress, these changes appear to be irreversible. There is a massive amount of investment being injected into Tibet from China, and it is telling of China's long-term ambitions in the region.

Since the implementation of China's Great Western Development plan in 2000, Tibet's economy has more than doubled in size, with an annual growth rate of over 11%. Most notably, after the opening of the Quinghai-Lhasa rail-line five years ago, the region has seen over $USD 20 billion in Chinese government investments in over 180 development projects. Included in these projects were the building of a 100,000 Kilowatt power-plant, an airport and a sprawling 60,000 km highway network that integrates Tibet's major cities and villages into a unified transit and economic grid. It is now even possible to travel daily by rail between the booming global financial centre, Shanghai and Tibet, one of China's most underdeveloped regions.

Over the next five years, the Chinese government plans to double its investments in the region. The goal is to integrate Tibet economically into greater China, while securing vital natural resources to fuel its rapid growth. It is reminiscent of the US's drive Westward under the mandate of territorial and economic expansion in the early 19th century; and noting the tensions that arise from the intersection of Chinese interests with the indigenous population's struggle to maintain their identity and autonomy, one could aptly label the Tibetan frontier, the 21st century version of the Wild, Wild, West.

This analogy is no exaggeration, either. While visiting the 7th century Pabongka Monastery outside Lhasa, our silent observations of monks in meditation were rocked by a series of dynamite explosions, rattling the ancient structure and startling us tourists, unaccustomed to the jarring sound of mining activity nearby. The monks simply smiled and continued their prayers. This was their peaceful resistance -- to carry on their culture and spiritual way of life in the midst of political and economic upheaval.

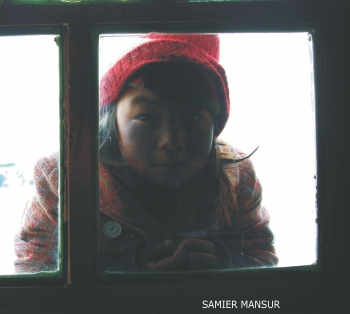

SAMIER MANSUR

SAMIER MANSUR

And this was the attitude of most Tibetans we encountered -- they faced life with a smile. But the creased lines on their faces told a deeper story: one of economic hardship and financial inequity, of a rough life spent farming and trading in harsh, dry and cold temperatures, of resentment brooding within. We shared laughs with them in the marketplace bargaining a few cents over fruits and souvenirs; we looked into each other's eyes as we tried to discern one another's life story; and we passed them on our long drives as they gathered by the dozens for lunch in the middle of expansive fields. There they shared their food while listening to Tibetan pop-legends on their hand-held radios sing of the beauty of Tibet, its culture and its people -- and for a few moments I could imagine them sitting back, recalling a time in which such concepts were not so revolutionary, but simply a facet of their very being.

And the Chinese soldiers and officials we encountered were not as cold and rigid as popular media have made them out to be. In many instances, we found them dressed in over-sized uniforms with facial features foreign to the land of their posting. They were youthful rookies, probably homesick and longing for their own homeland, or perhaps a young love in a distant province. Politics seemed to be the last thing on their mind -- this was simply a job, a vital source of income at that. Our inquiries over directions were addressed with proper care and attention; at each checkpoint they were courteous and efficient; and our curious glances were returned with curious looks and smiles, even while marching. Of course, having a foreign passport probably helped, but in general, caricatures don't tend to hold up well in the face of reality.

I did not experience enlightenment in Tibet, but I did come to a better understanding of the ever-changing nature of the world. While shuffling through the inner chambers of the Potala Palace, I stopped to linger a while in front of the Dalai Lama's old room. There stood his bed, his pillow, his slippers, all arranged in the same manner it was on the day of his hasty departure over half a century ago, as if awaiting his return. It was at that moment that the heavy realisation dawned upon me: there will probably be no return. Tibet will probably never be free. Even the Dalai Lama knows this, he stopped calling for an independent Tibet a long time ago.

The Tibet of Atisha and lore is no more; even his ashes now reside at Dharmarajika Monastery in Dhaka, nearly one thousand years after he breathed his last in a village just outside Lhasa. Change, it appears, is the only predictable variable of history.

If there is hope in the story of Tibet, then let it be one that sees the coming changes as one that will bring progress and opportunity, prosperity and stability to a land which has seen very little of either over the last century. Moreover, let our hope stem from the resilience of a people who have made their cause synonymous with our own highest aspirations: that of patience, of forgiveness, of freedom and transcendence. In a few generations, perhaps the romance of Tibet is all that we will be left with, after all. And that in and of itself is enough, for a beautiful idea that inspires is a powerful entity that can never be taken away -- not even with time.

Samier Mansur is an international policy consultant with the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI). He may be reached at samier.mansur@gmail.com.