Inside

|

An Incomplete Mission and a New Vision of South Asian Cooperation

DR. MIZANUR RAHMAN SHELLEY

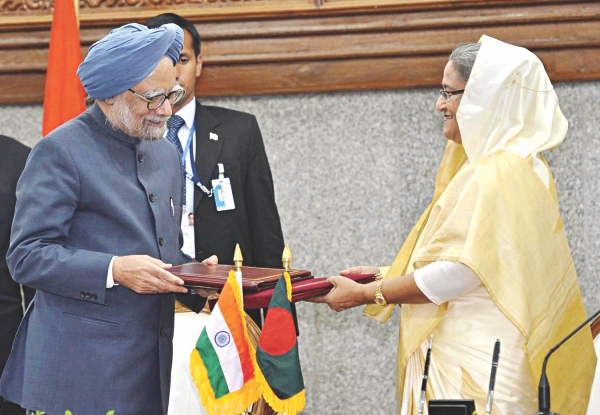

Reality inflicted an undeniable defeat on romance as the Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh left Bangladesh on the 7th September 2011 with his mission incomplete. The high notes of roaring hopes that heralded the start of the two-day visit of the Indian leader turned into low whispers at the disappointing end. The much expected agreements on sharing of the waters of common rivers Teesta and Feni could not be signed during the Prime Minister's visit. Ostensibly, Mamata Banerjee, the newly elected Chief Minister of the Indian province of Paschimbanga (West Bengal) (from which the Teesta flows into Bangladesh) threw the spanner into the works and that also at the last moment. According to media reports, she objected spiritedly to the quantity of Teesta water which the Indian central government had decided to give to Bangladesh.

PHOTO: PMO

PHOTO: PMO

Sharing of the waters of common rivers Teesta and Feni was not the only significant item on the agenda. The long awaited visit of the Indian premier was scheduled to achieve other major breakthrough in the relations of the two friendly neighbours. Among those were the matter of India's transit through Bangladesh to its North-Eastern States, an arrangement positively described as 'connectivity' and negatively called 'corridor', duty-free access to some Bangladeshi products to Indian markets, demarcation of un-demarcated portion of Indo-Bangladesh border, settlement of the issue of enclaves and land under adverse possession. As it transpired, the two most important issues, although apparently independent of each other, that of sharing Teesta and Feni waters and transit remained unresolved. Mamata's last minute stand against the proposed formula of water sharing stalled the Teesta agreement and as what seem to be the fallout, obstructed the finalization of transit arrangements. Although the leaders of both countries presented a brave face and held out hopes of resolving the issues in the near future, there was little doubt that for the time being high hopes of further cementing the friendly ties had been dashed to the ground.

The Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina, the architect of the season of renewal of Indo-Bangla friendship, justifiably lamented the unfair critic's stress on the failures. She rightly pointed out that these skeptics shied away from extolling the successes achieved by the visit of the Indian premier to Bangladesh. Among these are the agreements on the exchange of enclaves, an unresolved matter that since the departure of the British colonial rulers from the sub-continent in 1947, had virtually imprisoned thousands of enclave-dwellers in subhuman existence, duty-free entry of 46 Bangladeshi products into India, demarcation of hitherto un-demarcated portion of Indo-Bangladesh border and exchange of land under adverse possession. In addition, understanding was reached on import of Indian electricity into Bangladesh and educational and cultural exchanges.

All this represents no mean achievement. In the complex matrix of Indo-Bangladesh relations compounded by turns and twists of history, every little thing helps. In that context the other achievements, resulting from the Manmohan Singh visit, may assist overall improvement of neighbourly ties.

Nevertheless, one should not lose sight of the total scenario of interstate relationship in the South Asian region. The painful failures, though hopefully temporary, of settling the issue of sharing of waters of the Teesta and Feni rivers represents only the tip of the iceberg. Beyond and behind the failures lies the vast landscape or seascape, if you like, of the nature of the entities concerned and their interrelationship as shaped by centuries of distant and decades of immediate past history.

A holistic understanding of this backdrop may help in forging a new vision of interstate cooperation in South Asia. Realization of such a vision may finally remove the obstacles on the way of effective bilateral and multilateral cooperation in the sub-continent.

As a Bangladeshi analyst forcefully states: "The inter-state relations in South Asia appear highly paradoxical when viewed in the context of today's global politics. The region appears to be prepared neither to take the advantages offered by the recent changes in international arena nor to face the challenges posed by them. The conflict scenario in South Asia remains almost unaffected. Contrary to expectations, both intra and inter-state conflicts have become more intractable. In the context of today's world when cooperation among regional countries is most crucial South Asia has given regional cooperation within the framework of SAARC at best a low-key position."

Though the world around them has changed and changes have occurred in the sub national entities within themselves, South Asian nations seem frozen in political postures out of tune with transformed times. They are prisoners of the past. India and Pakistan are still vying for a politico-military predominance, which has become somewhat irrelevant to a transformed world and largely meaningless for the South Asian region itself.

The Indian concept of 'strategic indivisibility of the subcontinent' and India's role behaviour as an apex-power in the regional hierarchy seem to have contributed to the largely static political scenario of South Asia. Indo-Pakistan conflict has assumed a 'status quo character' while the conflicts marking the relationship of India with smaller neighbours such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal, have assumed “difficult dimensions.”

The preoccupation of the ruling elites of South Asian countries with outdated conflicts hangs round their necks as many a dead albatross. It reflects the tragedy of their inadequate exercises at nation-building. It is a testimony to the uneven development of their sub-national groups. It is a measure also of past failures of their development strategies that they borrowed from the capitalist West or the now-defunct socialist Soviet Union without realistic adaptation to their own socio-economic contexts. During the last decade, however, new and realistic adjustments of economic development policies by courageous liberalization measures by India and some of its neighbours have resulted in encouraging growth and progress.

The political arena, however, continued to suffer from 'inertia of rest'. The intra-mural failures of the ruling elites at political development through institution-building for resolution of the internal 'Centre-periphery' conflicts were and still are transformed into external conflicts. This has led to further regional instability. Thus, insurgencies in some Indian states become regional problems. Militant elements in Assam, Nagaland or Mizoram on the warpath against the Indian central authority spill over into Bangladesh. Some unhappy tribals of Bangladesh sought elusive patronage and succour in the sympathy and help of some quarters in India.

Similar experiences of cross-national ethno-political spillovers across Indo-Sri Lankan and Indo-Nepalese frontiers (separated by sea and foothills) enhanced the process of destabilization of the region. These tend to threaten regional peace and retard regional cooperation for human development. The entire process is bewildering. Whether it is a hangover from the colonial past committed to 'divide and rule' or a manifestation of transparent failure of several ruling elites of South Asia at nation or confidence building, it appears to be either surreal or sub-real. The realities unfolding in the world of the present times make these contentions and conflicts appear irrelevant and fruitless.

Political development seems to have been inadequate in South Asia. The states comprising the region have failed to fully cope with politico-ethnic and cultural demands of their peoples. In consequence, the core of the development process, human development has suffered the most. There have been some admirable success but the speed and spread has been much less than desirable. There are historic reasons for this failure. A major factor that led to South Asia's lack of expected success to cope with the present is its persistent preoccupation with the dead past.

The Roots of the Predicament

The changes in the world's North “are likely to intensify the common problems faced by the countries of South Asia in the context of their development process. These problems are epitomized in the relentless erosion in terms of trade, increased restrictions on their exports in the industrially advanced countries, insufficient transfer of resources (to South Asian countries), rising imbalance in their external payments and growing burden of external debts for most of these countries."

"In order to effectively combat and contain the adverse impact of the increasingly uncongenial external environment, the South Asian economies need to intensify their efforts and exercises for united and concerted action. Fortunately, the establishment of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in 1985 and its subsequent progress provide a concrete institutional framework for concerted action."

Despite several advantages such as a common civilizational heritage, shared history and potential integrative eco-systems South Asian countries remained unable to meaningfully and effectively cooperate in economic activities, trade and industry for development, centered round and resulting in human development. In spite of the SAARC, the situation does not seem to have registered any significant improvement. Even on the bilateral plane the record is less than satisfactory. The obstacles on the way of economic and business cooperation between India and Bangladesh even at the present friendly times illustrate these unfortunate trends.

Similar disabilities mark the political sphere. For too long these inabilities have been sought to be explained in terms of external influence and intrusion. In South Asia, Superpower-rivalry, intensified, complicated and distorted by other extra-regional forces, have been pinpointed as the root-cause of the politico-economic barriers within the area barriers which drained the essence of the region's vitality and energy and turned it into a graveyard of development efforts.

The major features of this complex phenomenon that goes beyond politics and subordinates considerations of human and economic development, are reflected in the persistent matrices of mistrust and distrust between India and her neighbors.

As the noted Indian writer and journalist Pran Chopra observe“…far from facilitating regional cooperation, the overhang of history has cast a shadow upon South Asia, creating a fog of mistrust in which the problems of the centrality of India and the disparity between India and its neighbours loom even larger than life.”

In the bipolar world that existed until the nineteen nineties, all this could be sought to be explained in terms of a divided world where contending Superpowers fought for domination and influence. In the emerging world, with a unipolar North and an increasingly polyarchic South, such efforts are bound to be fruitless. The various regions and nations of the world from nineteen nineties have been nakedly exposed to harsh winds. These are winds of new realities. These emerging realities are centered round people's hopes and demands for a better quality of life. A new vision of politico-economic planning and programming and management based primarily on considerations of human development, therefore, needs to be adopted and realized.

South Asia : The Way to Faster Development

The elites in several South Asian countries need to realize the harsh truth that their nations and their region as a whole are still lagging behind in human and economic development. They need to understand that what divides and devitalizes their region and prevents the nations in the area from cooperating for development and progress is not merely elite dissent and conflicts. The root of the trouble lies in their several and combined inability to come to grips with the new emerging realities. The collapse of the hitherto existent bipolar northern order and the post 9/11 global developments have unleashed forces of tectonic dimensions. In the resultant scenario, the continental plates are moving with astronomical speed.

PHOTO: AFP

PHOTO: AFP

The world in the north has changed. The Asia-Pacific region (meaning the East and Southeast Asian nations) has changed. South Asia seems unable to change fast and move forward rapidly. It remains, politically and economically, a captive of the unhappy part of its past. Yet until even three or four centuries ago it was one of the most prosperous regions of the world. That three- millennium long proud and prosperous past may still inspire the leaders and peoples of this part of the world to move in tandem for a better future. In order to succeed, the efforts to achieve such a bright future must be spearheaded by the opinion leaders of the South Asian countries.

This most important struggle can only be won if the opinion elites of all nations of South Asia underscore that the principal threat for South Asia, in these transient times, is from challenges issuing from common problems of poverty, hunger, illiteracy and malnourishment.

“The political, intellectual, social and business leaders in South Asian countries need to strongly reiterate the undeniable reality that their countries constitute the front-line states in human kind's ongoing war against its ancient enemies: poverty, hunger, malnourishment, ignorance, illiteracy, superstition (and environmental degradation).”

“This realistic realization and consequent concerted action can secure the ramparts of South Asian democracies. Secure in their well-governed democracies these countries can move in unison towards a better future forged by cooperation. Prime ministers Manmohan Singh and Sheikh Hasina have signed a framework agreement of greater and enduring bilateral cooperation. For such agreements, bilateral or multilateral, to be meaningful and lasting an effective framework of similar mindsets need to be in place in the countries of South Asia.”

Marx and Engels sounded in The Communist Manifesto: “Workers of the world unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains”. South Asian opinion shapers may do well to adopt the call and say: “Leaders and peoples of South Asia unite, for you have nothing to lose but your poverty.”

The author, founder Chairman of Centre for Development Research, Bangladesh (CDRB) and Editor quarterly “Asian Affairs” was a former teacher of Dhaka University and former member of the erstwhile civil service of Pakistan (CSP) and former non-partisan technocrat Cabinet Minister.