Inside

|

SK ENAMUL HAQUE

SK ENAMUL HAQUE

Road Kill

SYED ZAIN AL-MAHMOOD delineates a holistic “Safe Systems” approach towards reducing road accidents.

At the inquest of the world's first road traffic fatality on August 17, 1896, the coroner was reported to have said: “this must never happen again”.

More than a hundred years on, 1.3 million people are killed in road accidents annually, 3,500 lives lost per day. As many as 50 million are injured and suffer disability every year. The World Health Organization (WHO) says road traffic injuries are the leading cause of death globally for those between 10 and 24 years of age, beating out diseases such as malaria and tuberculosis.

At more than 60 deaths per 10,000 registered motor vehicles, Bangladesh has one of the worst crash rates in the world. We are right up there with war-ravaged countries like Sierra Leone and Liberia. Compare this to India's 25.3, Malaysia's 5.5 and America's 2.1 and it becomes clear that something is rotten on the roads of Bangladesh.

Although the official figure for road deaths is three to four thousand a year, independent studies by international agencies such as the UK's Department for International Development (DFID) have suggested the actual death toll in Bangladesh could be three times as high. The number of people seriously injured in road crashes is estimated at more than 1,00,000 each year.

In cold, hard economic terms, road crashes could be costing Bangladesh two percent of its GDP, says the World Bank -- roughly equivalent to the total foreign aid received by the country in a given fiscal year.

But despite the appalling dimensions of the problem, road safety ranks very low on our list of priorities. Road crashes kill more people than malaria or TB, yet the government hardly notices. NGOs pay lip service. News editors use road traffic accident stories as fillers on page four. Until, of course, we lose people like Tareque Masud and Ashfaque Munier Mishuk.

The horrific death of two of Bangladesh's most talented media personalities -- director Tareque Masud and cinematographer Mishuk Munier -- in a road crash outside Dhaka has once again thrust road safety into the spotlight.

And once again, our policymakers seem intent on barking up the wrong trees.

In the wake of the tragedy, both the government and the public have been shaken out of their inbuilt apathy towards road safety. The communications minister has criticised the finance minister for not providing adequate funds while the finance minister has blamed the communications minister for a lack of maintenance and supervision. There have been calls for the enactment of new laws carrying the death penalty for drivers who cause accidents.

But draconian laws won't stop road death. Science will.

But draconian laws won't stop road death. Science will.

Strategists worldwide stopped thinking of road crashes as a mere transportation issue long ago and recognised it as a public health and sustainable development problem. Since 2004, when the WHO launched its pioneering World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention, experts have been calling on governments worldwide to adopt a scientific approach towards road safety. This Safe Systems approach has seen road death fall dramatically in many countries over the last decade.

In the words of Lord Robertson, former British defense minister, chair of the Make Roads Safe global campaign and himself an automobile crash survivor: “We need forgiving roads.”

***

The Safe Systems approach has at its heart the concept that roads should have built-in mechanisms that will deter accidents in spite of human error, and if accidents do occur, the road environment will minimise the possibility of death. This approach marks a fundamental shift in thinking about road crash prevention.

The traditional approach to road safety puts the onus on the road user -- drivers, pedestrians, cyclists. It is held that road users through training, supervision and retribution can cope with the demands of traditional highways without causing accidents. From that view it follows that when accidents do occur, they are the responsibility of the individual road user.

However, research carried out in Scandinavian countries indicates that even if all road users complied with road rules, fatalities would only fall by around 50% and injuries by 30%.

It has long been accepted in other activities such as industrial safety, the railways and aviation, that the operator (be s/he pilot, driver or skipper) is only one part of a dynamic system, with his specific limitations as to performance over time, with the effects of fatigue and alcohol, and predictable error rates. Therefore the other parts of the system, in this case the highway, the vehicle and the traffic management components must be designed with a recognition of the limitations of road users.

The systems approach on the other hand recognises the fallibility of road users and their intrinsic limitations and seeks to minimise the consequences by failsafe design and operation. Instead of asking, “Who is the silly ass that crashed into that roadside pole?” it asks, “Who is the silly ass who put that pole there for a motorist to crash into?”

Many years ago, when giving evidence in court, a well known traffic engineer in England, John Leeming, noted that when a driver was found guilty of defective driving s/he was fined and sometimes sent to jail -- should not a highway engineer if found responsible for a defective junction design receive similar treatment? At the time that was considered highly subversive, but it logically follows from the recognition that the driver is only one element in an interactive system.

The Safe Systems approach is about acknowledging: 1. human beings make mistakes and crashes are inevitable 2. the human body has a limited ability to withstand crash forces, 3. system designers and system users must all share responsibility for managing crash forces to a level that does not result in death or serious injury and 4. it will take a multisectorial approach to implement the Safe Systems in any given country.

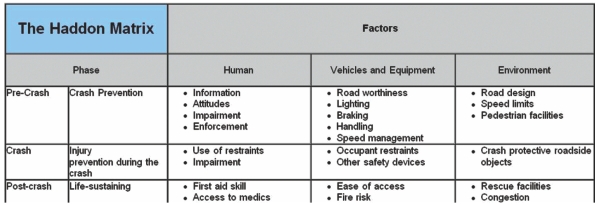

The approach, advocated by the WHO and road safety agencies around the world, takes into account the interaction of three factors -- human, vehicle and environment during three phases of a crash event: pre-crash, crash and post-crash.

Implementation of the “safe systems” model has brought significant reduction in levels of traffic-related death and injury in many countries, including some developing ones.

***

The emphasis on a more scientific approach is embodied by the International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP). Working with governments and local agencies, iRAP targets high-risk roads and proposes affordable changes, delivering significant reductions in deaths and serious injuries. In a country like Bangladesh where crash data is notoriously difficult to come by, an assessment programme is desperately needed.

“We are very pleased to be planning a pilot project in Bangladesh,” John Dawson, chairman of iRAP told this writer at the First Global Ministerial Conference on Road Safety in Moscow in November 2009.

The pilot study took place in March 2010. With the support of the FIA Foundation, the International Road Assessment Programme undertook a safety assessment of the N2 Highway, connecting Dhaka with Sylhet.

The N2 is a new highway, with major rehabilitation and widening completed as recently as 2005 at a cost of US$330 million with financing from World Bank. But crash death rates show “better roads” are not necessarily safer. Traditional road design aimed to reduce the number of crashes by widening and straightening roads. But that has no impact on the rate of death and disability because people simply start to drive faster.

“Today's systems assume that humans don't make mistakes. One mistake and you might be killed,” said road safety expert Greg Smith who led the pilot project. “But roads should be engineered in such a way that even if the driver loses control, the infrastructure should be able to mitigate the seriousness of the crash. It's all about kinetic energy control.”

The iRAP team uses a special survey vehicle that takes a “snapshot” of the road every 100 metres. The drive-through inspections involve a continuous record of road infrastructure elements, including pavement condition, road markings, pedestrian footpaths, over-bridges and roadside hazards.

“We don't want gold-plated roads,” says Greg Smith, who is regional director, Asia-Pacific of iRAP. “With a scientific approach, sometimes a coat of white paint will save lives.”

In the course of his work with iRAP, Greg has seen some dangerous roads, but he admits that the highways in Bangladesh are right up there with the most treacherous. “There is a mix of fast and slow traffic, leading to very high overtaking demand. There is no median barrier in most areas, which increases the risk of frontal collisions. When you take into account the high pedestrian flow across the road, you can see that it is a disaster waiting to happen.”

Safe Systems countermeasures can often involve little more than adopting modern signing, hazard markings and junction layouts. Well-designed intersections, safe roadsides and appropriate road cross-sections can significantly decrease the risk of a crash occurring and the severity of crashes that do occur. Dedicated footpaths and bicycle paths can substantially cut the risk that pedestrians and cyclists will be killed or injured by avoiding the need for them to mix with motorised vehicles. Dedicated lanes for motorcyclists can minimise the risk of death and injury for this class of road user.

“We know how people are killed, and what can be done to stop it,” said Greg Smith. “All we need is the political will to implement these countermeasures.”

The Safe Systems model expects high investment returns. For example, for each pilot country the iRAP programme estimates benefit to cost ratio greater than 10. In Malaysia for example, an investment of US $180m is expected to deliver US $3bn in benefits and prevent over 30,000 deaths and serious injuries over 20 years.

***

ZAHEDUL I KHAN

ZAHEDUL I KHAN

In recognition of the staggering burden road crashes place on developing economies, the United Nations has declared 2011-2020 the Decade of Action for Road Safety, with the aim of saving 5 million lives, 50 million serious injuries and US$ 5 trillion over the course of the next 10 years.

The WHO, the lead international agency tasked with coordinating the Decade of Action, has drawn up an action plan based on the Safe Systems model. The plan consists of the Five Pillars of Action: improve road safety management capacity, build safer roads, use safer vehicles, raise awareness among road users and improve post-crash response.

“There are specific guidelines and tools for all the five pillars, and indicators with which to monitor progress,” says Prof. Mazharul Hoque, a road safety expert with the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (Buet). “We must devise a national action plan in accordance with the global guidelines.”

At the national launch of the Decade of Action in Bangladesh on May 11, Communications Minister Syed Abul Hossain committed to implementing the global plan of action. One of the highlights of the launch was the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the Roads and Highways Department (RHD) and the International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP).

Yet, many would argue the situation is rapidly getting worse, and there are formidable barriers to implementing an effective action plan based on the Safe Systems model in Bangladesh. One problem is the absence of a coordinating “lead agency” to oversee the plan.

Currently the National Road Safety Council (NRSC) is the apex committee which steers road safety activity in the country, and the Bangladesh Road Transport Authority (BRTA) is the coordinating agency. But the NRSC may be too big and unwieldy to be a regular coordinator while many have questioned whether the BRTA is capable of working as lead agency with its current capacity.

The NRSC Secretariat was created within the BRTA in 1997, which was subsequently converted to the Road Safety Cell (RSC) in 2001. In a sign of government apathy, this cell was abolished in 2009 and road safety was incorporated into the enforcement activities of the BRTA.

Many analysts suggest the BRTA is swamped with its core activity of regulating the road transport sector. If it is to function as lead agency, a separate cell must be created and a dedicated set of experts must be hired to do the job, with fund set aside for road safety activities.

Taken in isolation, stricter legislation or public awareness initiatives won't be able to prevent the tragedies that are played out on the roads of Bangladesh every day. A combination of scientifically designed roads, better law enforcement and road user sensitisation -- Safe Systems -- will succeed in turning the tide.

The Safe Systems approach to road safety requires a concerted effort from government including parliament, the police, road users, NGOs and the media. The WHO is calling for a “culture of road safety” and it is this culture that must be fostered in Bangladesh to tackle the scourge of road death.

Syed Zain Al-Mahmood is a journalist who writes about public health, human rights and sustainable development.