Inside

|

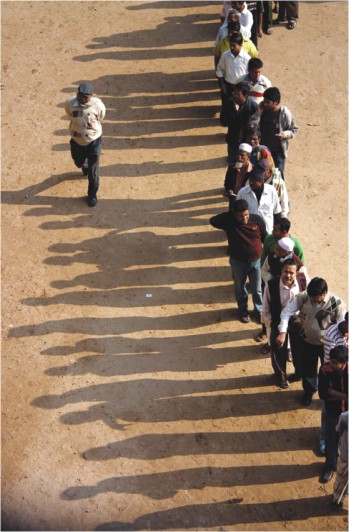

Legitimate vs. Authoritarian Policy Making SYEED AHAMED outlines the history of policy making by elected and un-elected regimes in the past -- and opportunities ahead for the current government.

Bangladesh's experience with public policy making over the past four decades has been perplexed by an awkward political dilemma. On one hand, democratic and legitimate reform initiatives have endured barriers to implementation; while on the other, many successful reform initiatives have suffered from lack of legitimacy. Lack of authority has always been a barrier to policy reform, while public support and legitimacy has been the most essential feature of public policy. Balancing the two is difficult and remains as a litmus test for any policy maker. Ironically, our policy makers have always preferred the easier option -- acquiring authority and ignoring legitimacy. Though authoritarian governments may seem more successful in implementing reforms, authoritarianism often leads to autocracy and reforms achieved through this process are not beneficial for the country. This article briefly explores the dilemma between legitimate and authoritarian policy making in Bangladesh. For that, it also analyses the changing roles and relationships of four most influential policy makers of the country -- the politician, the military, the donor and the bureaucrat. The legacy of Bangladesh's public policy making dates back to the 17th century, when the East India Company created the 'civil service' to facilitate its trade. When it expanded its activities from trade to colonial dominance, the functions of its civil service changed from managing business to running government administration in its colonies. The civil service emerged as corps d'elite in the Indian subcontinent with executive and judicial power to formulate and execute public policies in the absence of local political dominance. The political leadership could enjoy policy-making role in the post-colonial Pakistan for a brief period of time. In 1958, the political government was overthrown by a military coup. Under the military rule, the bureaucrats restored their lost command and enjoyed their supremacy until 1971. From legitimacy to dominance (1971-1975) The first Five Year Plan of the country categorically noted that the bureaucrats could be neither the innovators nor catalytic agents for a social change, and “it is only a political cadre with firm roots in the people and motivated by the new ideology and willing to live and work among the people as one of them that can mobilize the masses and transform their pattern of behaviour” (First Five Year Plan, 1973). AL promised nationalisation of heavy industries in its manifesto for the 1970 national election. AL leadership took 'socialism' as one of the four founding principles of Bangladesh's Constitution. In March 1972, within three months of independence, the government announced major large-scale nationalisation of industries across the country. It is, however, argued that Bangladesh needed to nationalise the industries abandoned by the Pakistani owners and ideology had very little to do with the spread of nationalisation during 1972, though this doesn't explain the nationalisation of Bengali-owned enterprises in jute, textile, banking and insurance sectors. The recommendations of the government-appointed reform committee, known by the name of its chairman as 'Chaudhury Committee', were also highly ambitious, radical in nature and aimed at a complete overhaul of the inherited bureaucracy. Implementation of these recommendations became the litmus test for the government's political commitment to de-bureaucratise the policy making process. The committee was set up during the high time of post-independence sanguinity. But, by the time the recommendations came in, the socio-economic conditions of the country changed. A number of diplomatic and environmental disasters took place during the first three years of its independence that directly and indirectly encumbered the reform process. A combination of natural and economic causes -- including the flood of 1974, post-independence capital flight, mismanagement of monetary policy and price hike in the international market -- culminated into widespread starvation and the Famine of 1974. To make things worse, Bangladesh entered into a difficult food aid conflict with US, whereby US postponed its food supply in a bid to put pressure on Bangladesh to stop jute export to Cuba. By the time the diplomatic impasse was settled and the flow of American food resumed, the autumn famine was largely over. When the country entered into this economic crisis and famine, political unrest erupted across the country and the regime's immediate focus turned to 'establishment of control'. On January 25, 1975, the parliament amended the Constitution to introduce the presidential form of government replacing the parliamentary system. It established a one-party political system and curbed the powers of the national parliament. While it is often argued that BAKSAL intended to bring the elitist bureaucracy under political leadership, the chiefs of military and para-military forces and Secretaries of all ministries were made the members of the central committee of BAKSAL. After consolidating absolute power over the governance system in 1975, the government began to implement some of the reform agendas suggested by the Chaudhury Committee. The Services Reorganisation Act 1975 was issued to incorporate the recommendatios of the Committee. But soon the country entered into its first of many military coups. On August 15, 1975, the armed forces seized the government in a predawn coup and Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was brutally assassinated along with most of his family members. Towards authoritarian militarism (1975-1990) When Major General Ziaur Rahman assumed power following the August 15 assassination, he re-established a 'bureau-military state'. The civil-military bureaucrats dominated the decision-making structures of the state apparatus, including the Council of Advisors for the President and the National Economic Council. Though privatisation and policy reforms under aid conditionality were not new to Bangladesh, incorporation of these two apparently separate issues accelerated the privatisation process during the post-1975 period. Zia actively promoted private entrepreneurship and accelerated the privatisation process by introducing a programme of term loans extended through various development finance institutions, which had in turn been underwritten by loans from the World Bank, ADB and other donors. Some 247 state-owned industries were privatised between July 1975 and June 1981. He also opened up the market for international trade. When Major General HM Ershad assumed power, eventually after Zia's assassination, the privatisation process got associated with a series of new credit programmes announced by the Bretton Wood Institutions -- namely World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF). Through these programmes, donor agencies strengthened their role in Bangladesh's public policy making process.

In March 1986, IMF introduced a highly conditional and concessional loan scheme called Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) to support structural adjustment in low-income economies. Under these commitments, the process of privatisation continued and some 125 industries were privatised during July 1981 to June 1991. While the Structural Adjustment programme has been highly discredited in most developing countries, it was a very 'active' reform programme during the 1980s. Towards the end of his tenure, in 1990, Ershad signed another loan scheme under Enhanced Structural Adjustment Facility (ESAF). It was approved on August 10, 1990, only four months before the military government was forced to resign following strong public resistance and students' movement. The period between 1975-1990 under military regimes was one of the most active periods for administrative and policy reform initiatives. A number of pay and reform committees were initiated and the successive authoritarian governments actively implemented many reform suggestions. Return of legitimacy and inaction (1991-2010) Though PRSP has been criticised as an extension of the discredited forerunner -- structural adjustment programme (SAP) -- it couldn't become an active policy reform vehicle during the democratic rule. Bangladesh's experience with the rise and fall of privatisation and success and failure of SAP and PRSP during military and democratic regimes respectively, makes one thing clear -- policy reforms in this country have been more successful in terms of implementation during authoritarian regimes. Does it mean authoritarianism is better than democracy? Well, not exactly. Dilemma of authoritarianism

The military rulers and donor community were not the only members of policy network to support privatisation to its success. A survey conducted by Islam & Farazmand (2008) showed that out of 120 senior civil servants interviewed, 60.8% found privatisation positive for administrative development; and 84.6% believed that 'privatisation of public sectors has positive effects on job performance'. Success of privatisation process shows the effect of donor, ruler and bureaucrats' unity in an authoritarian policy network -- for good or for bad. For privatisation, it was not for the good. When the first interim government came to power, the Bangladesh Board of Investment (BOI) carried a survey to assess the performance of the industries that were privatised during the 1970s. The report, submitted in March 1991, provided a very grim picture of the privatised industries. According to the report, out of 290 enterprises for which information had been collected, 52 percent units were closed down, of which, nearly half were using the property for alternative purposes. Later on, when the BNP government came to power, the Minister of Finance entrusted the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS) to carry on a similar survey on 205 enterprises privatised since 1979. The findings of the study were similarly disappointing. Of the 205 units, 40.5% units were found closed and 4.9% were proved to be non-existent. These findings coincided with the BNP government's apathy to speed up the privatisation process and establishment of Bangladesh Privatisation Board to oversee the functions of the process. Authoritarianism may speed up the reform process, but the reform may not be the one the country needs. Following a long and deadly political conflict towards the end of 2006, Bangladesh entered into a two-year regime of un-elected government. Quasi-military in nature, the Caretaker Government re-militarised the public policy making process. The Military Chief became the de-facto ruler of the country and many top government institutions were appointed with former military personnel. During this time, the Bangladesh Investment Climate Fund (IFC-BICF) was established as a multi-donor advisory facility to fund and advise the Bangladesh government to carry on various reform initiatives. The Regulatory Reform Commission (RRC) was set up to oversee the regulatory reform programme while Bangladesh Better Business Forum (BBBF) was established to deal with non-regulatory issues. While we condone all un-elected and illegitimate regimes, RRC had one significant feature, which couldn't be correlated with past military regimes. Bureau-military personnel did not overwhelm the Commission. However, the authoritarian nature of the regime facilitated the fast implementation of most of the Commission recommendations. When the country returned to democracy through an electoral-transition in December 2009, the Commission became inoperative. The current government has a unique opportunity to balance the authority and legitimacy issue in public policy reform. It has been given an overwhelming majority in the parliament; something the government is using to implement its political, constitutional and legal agendas. We hope the government uses this legitimate authority to revive or re-establish an active Commission like the RRC to continue an active yet legitimate policy reform initiative. Syeed Ahamed is a public policy analyst by training and a member of Drishtipat Writers' Collective (DWC).

|