Inside

|

Building the Chars

|

SK ENAMUL HAQ |

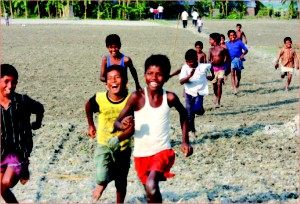

WAMEQ RAZA tells a tale of survival on the chars, aided by the government and NGOs.

The story of land grabbing in Bangladesh is as old as time itself. Among the copious varieties of land grabbers in Bangladesh, first and foremost are the contemporary ones who encroach on rivers and waterways in and around the cities, primarily for commercial benefits. Then there are those who go into the rising chars with their lathiyal bahini and claim them as their own, also mostly for commercial benefits. Lastly, there are those who go into new chars as they have no other options. The first two groups inevitably fall into the wealthy and influential categories. The latter, however, typically constitute destitute families who, due to abject poverty and lack of viable alternatives, will go into newly formed chars in the search of better livelihoods. But due to a lack of infrastructure, basic human security against nature and fellowmen with arms, life morphs into something from a bad nightmare.

The story of Kaiser Begum takes place mostly around Boyar Char, near to mainland Noakhali. Second of five children, Kaiser Begum was born in Ramgati and moved to Hajari Char when she was young. Her father earned a living making pottery, while her mother was a homemaker and she recalls having a very comfortable life as a young girl. But as she grew older, the situation changed. Her father, for unknown reasons, would end up disappearing from home for long periods of time and it became an increasing struggle for her mother to feed the large family. Her mother was ultimately forced to take the children out of school and send them to work. More often than not, the entire family was forced to sustain on plain rice with chillies.

Like many poverty stricken families, where the girls are wedded off at a very young age, Kaiser Begum was no exception when she was married off to a man from Ramgati at the age of 15. After the wedding, she moved back with her husband to her birthplace. Her husband was not a wealthy man and worked as a day labourer from which he earned Tk.100-200 per day. Rather than being provided for and protected by her husband, Kaiser Begum became a target for domestic violence from both her husband and her mother-in-law as her parental family could not provide any dowry. However, after a few years when her mother-in-law passed away, they decided to move to Boyar Char in 1998. At this point she had two daughters.

Boyar Char has a familiar history. When it first surfaced during the early 1990s, surrounded by salinated water, it was a large mass of barren land. Typically, the Department of Forestry from the government move in for approximately 20 years as new chars develop. This time period is required for plantation and management of forests (mostly mangroves). The objectives of the Forest Department activities are to accelerate accretion, stabilise the land and protect the mainland against storms and cyclones. However, some of these chars experience the influx of people much earlier than the 20 years. Little by little, people from surrounding regions began moving in to the area, and along with these people came the bahinis, a vicious group of land grabbers. Bloody conflicts ensued for dominance and were eventually won by a small-framed man known as Solayman Commander with his group of bandits. They started allotting land to the newcomers as if it was their own and would tax them on a regular basis.

|

SK ENAMUL HAQ |

The day-to-day living conditions were no better either. The availability of anything but salinated water for drinking or other uses was a seemingly unattainable dream. There were no health facilities or doctors and the death rate was quite high to illnesses. When they moved to Boyar Char, Kaiser Begum says that the place was comparable to a mangrove swamp. After purchasing some land with Tk. 5,000 that her mother had given her, it took Kaiser Begum and her husband nearly a year to get the land cleaned up. Within the next few years, she had two more daughters and one son. Coping was difficult with so many mouths to feed. More often than not, they would have to borrow rice and other food items from neighbours, who understandably faced deficits of their own. In addition to that, they had to deal with the bahinis who would demand taxes precariously. During such an incident when they weren't able to pay, the bahinis severely beat her husband and set fire to their house. Her husband quit working as a day labourer at that point for fear of his family's life if he stayed away for too long and began working on their field to cultivate crops.

This is when the tides turned. Funded by the Netherlands Embassy, under the umbrella of the Char Development and Settlement Programme (CDSP), nongovernmental organisation (NGO) BRAC ventured into the area with the help of five local NGOs and with the full backing of the Government of Bangladesh. Along with the government and the armed forces, the bahinis were driven out of the area. Paved roads connecting mainland Noakhali and the char were developed.

Fresh water lines were installed, giving the local population a sigh of relief from having to continually drink salinated water. Schools were built as well, along with the much needed cyclone shelters.

The CDSP contains a number of components that complement each other to promote a holistic approach to livelihood improvements for the participating women. As a participant, Kaiser received training in social forestry and received seeds for investment in addition to a sanitary latrine for her household. After the completion of mandatory training, she took out a loan of Tk. 3,000 and spent it for personal expenditures. However, she paid it back from her own earnings from some of the other projects. The year after that, she took out another loan of Tk. 4,000, which she used to buy a calf, which she later sold for a profit. She took another loan soon afterwards to finance her daughter's wedding and recently undertook another loan of Tk. 8,000 with which she bought two more calves.

In the present day, the smile on Kaiser Begum's face is infectious as she describes the difficult time she has had to pass. Her house is surrounded by trees which she had planted in 2005 from the CDSP grant and on the side is a medium-sized nursery from where she sells seedlings. Her house is no longer a shack but a house with tin walls and four rooms.

The programme had so far helped approximately 8,500 families in the Boyar Char to develop themselves and build better lives. Many participants such as Kaiser no longer have to live in fear of starving or the bahinis. Impact assessment of the CDSP revealed that programme intervention significantly increased the per capita income level of the participants along with higher living standards compared to their counterparts. And the cherry on top is that the respondent women's awareness on various social and legal issues were found to be affected positively by programme intervention.

There are several lessons to be learned from this programme. The success of the CDSP is remarkable and the fact that the programme was implemented with the full support of some of the local NGOs and the Government of Bangladesh (GoB). This strong partnership made the situation significantly more conducive to such positive outcomes. It is clear that these NGOs are more aware of the ground realities and situations and are in a position to deal with localised problems such as social unrest and so forth more efficiently and effectively. On another count, due to the smaller size the local NGOs have limited exposure and experience in comparison to organisations such as BRAC. Through this joint exercise, they gained significant amounts of knowledge and skills that they would be able to use in their future activities. One of the important lessons that came out of the CDSP exercise was to work in conjunction with the locals when dealing in difficult and hard-to-reach regions such as the Boyar Char. And last but not the least, in terms of cooperation with the GoB, this factor alone made the project infinitely more feasible. The success of this project is evidence alone that if the public and private sectors cooperate, no challenge remains insurmountable.

Another lesson, albeit copiously repeated, is that microfinance is a tool that is effective for certain groups of people under the poverty line. The real approach to poverty alleviation must be holistic and longer-term. When the participants reach a certain stage in terms of being able to effectively address their basic and immediate needs, they can start to think about the future and the paths to invest in it.

Wameq Raza has a BA from Ithaca College in USA and an MA from University of Sussex in UK. He works for BRAC as a Senior Research Associate.