Inside

|

Out of the Farm, Into the City:

Structural change and economic development

|

PALASH KHAN |

JYOTI RAHMAN points to some things to think about in the lead up to the national budget.

Dhaka was a much smaller city a few decades ago. Driving to the city from Aricha, one would see construction works around the National Memorial in Savar and then nothing but miles of paddy fields and marshlands until Louis Kahn's building. Approaching via Mymensingh Road, the statue of the freedom fighter stood tall in Joydebpur junction, and then there was little sign of urbanity, save the new airport, until one reached the old airport at Tejgaon. Mirpur and Gulshan were their own municipalities. Uttara didn't exist. Ashulia was under water.

Noorul Quader's Desh Garments started operation in 1980. Emigration to the Gulf and elsewhere had begun a few years earlier. Over the following decades, both remittance and garments have boomed. Dhaka's conurbation now incorporates both Savar and Joydebpur.

Back then, Aricha and Mymensingh Roads were narrow, low-lying strips where rickety minibuses dangerously carried passengers. Now, these roads are elevated from the surrounds, and their four lanes are full of robust big buses (that, sadly, still carry passengers dangerously). And in Ashulia Bazaar, there are dozens of 'cosmetics stores', selling lipsticks, shoes, bags, mirrors and a few other things to people working in the nearby garments belt.

This, dear reader, is economic development in practice.

Economic development means rising standard of living (of which, GDP per capita is a good proxy). Typically, a less developed economy is dominated by a large agriculture sector that employs bulk of the labour force. The process of development involves the surplus labour leaving the farm for factories in the city, where higher wages reflect rising productivity. Higher incomes, in turn, generate demand for the service sectors such as retail trade and transport, whose increased profits in turn lead to more employment and income. And so it goes. Over time, as an economy develops, it becomes less agrarian -- industry and services sectors increase their share of total production and employment.

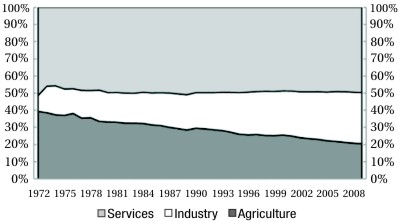

Structural change along this line is a common feature of all countries that have undergone material development in the past few centuries. Bangladesh is no exception (Chart 1). Agriculture used to make up two-fifths of total production at independence, while today it makes up about a fifth. Back then, industry counted for slightly more than a tenth of total production, now it makes up nearly a third.

Chart 1: Share of total production by sectors (1972-2009)

Source: World Bank World Development Indicator.

However, these structural changes, like the growth processes of individuals -- think of puberty or teen years -- are not painless. And there are major policy challenges along the way. In the lead up to the Budget, are we thinking about these challenges?

Out of the farm

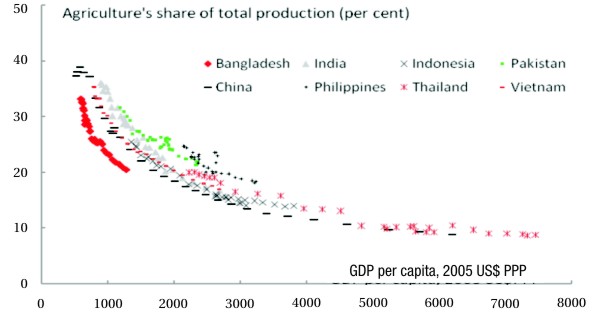

Let's start with the agriculture sector first. Chart 2 plots agriculture's share of total production against GDP per capita for selected Asian countries over the past three decades. There is a clear inverse relationship -- as GDP per capita rises, the economy becomes less agrarian. When GDP per capita is less than $1,000, around two-fifths of the production in the economy is in its farms.1 As GDP per capita doubles to about $2,000, agriculture produces only about fifth of the economy's total output. As the economy becomes richer, agriculture's share of total output falls to a tenth and less. This inverse relationship was also true for East Asia in the middle of the 20th century, and Europe and North America earlier.

Bangladesh seems to be moving away from agriculture earlier than its neighbours. In 1980, when GDP per capita was about $600, agriculture made up a third of Bangladesh's total output. By 2009, GDP per capita had more than doubled to be near $1300, and farm's share of total production had already fallen to a fifth.

It's important to stress that farm's output isn't falling over time. Agricultural production rises as the economy grows, but the non-farm sectors grow much faster. For example, agricultural output in Bangladesh doubled in the two decades to 2009, while output from the industry sector quadrupled over the same period.

Accurate employment data for developing economies are hard to come by. But wherever available, they paint a similar picture as Chart 1 -- as the economy becomes more prosperous, farm's share of total employment falls. For example, over three-fifths of Bangladeshi workers were employed in the farm sector in 1996 -- by 2005, the share had fallen to less than half.

Chart 2: Agriculture's share of total production vs GDP per capita (1980-2009)

Source: World Bank World Development Indicator.

Even though agriculture's share of both total production and employment fall over time as an economy develops, the sector tends to employ proportionately more people than its share of total output might suggest. For example, while nearly half of Bangladeshi workers worked in the farms in 2005, they produced less than a quarter of the output that year. This reflects the fact that productivity -- output per worker -- is lower in agriculture than elsewhere in the economy. In 2005, average Bangladeshi farmer produced output worth about $750, while the average industry worker's output was $3,200.

Of course, this is to be expected. Typically, farming is the 'traditional' sector that lacks the technology and capital that factories of the 'modern' sector take for granted. As noted initially, economic development is characterised by the transformation of the economy from traditional farms to modern industry and services.

And it's not like farmers become less productive as the economy develops. Far from it. Between 1996 and 2005, for example, output per farmer rose by 46 per cent in Bangladesh. This is also matched in terms of land productivity -- for example, yield per hectare of land in Bangladesh's rice sector has increased faster than in India or Pakistan in recent years.

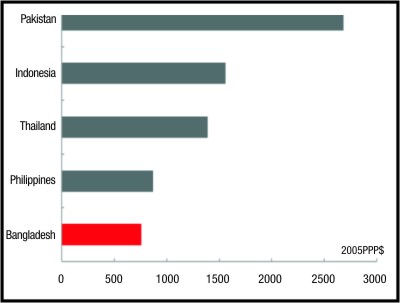

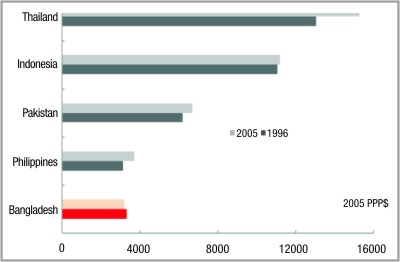

These improvements notwithstanding, labour productivity in Bangladesh's agriculture sector was still considerably lower than comparable Asian economies in 2005 (Chart 3). This should not be surprising. The land holding pattern in Bangladesh -- of small and dwindling plot size -- may not be conducive to large-scale investment needed to mechanise, and thus lift the productivity in, the country's farm sector.

The political economy of land distribution is of course a vexed one. Further complicating the land use issue is the fact that Bangladesh is urbanising at a rapid pace, and there is an aspiration to industrialise rapidly. However, the very process of urbanisation and industrialisation will put further pressure on domestic farm production.

Beyond subsidised fertilisers and credit, is there any policy agenda for the agriculture sector?

Chart 3: Output per farmer, 2005

Source: World Bank World Development Indicator; author's calculation.

Into the city

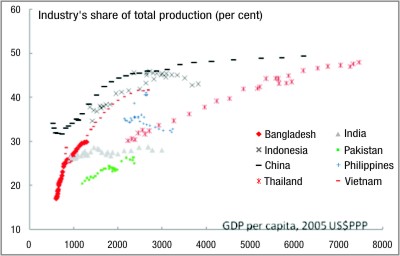

Over the past two centuries, in developed economies around the world, as farm productivity had risen, it inevitably released hundreds of thousands of surplus labourers, who migrated to the cities. Economic development had involved this surplus labour being employed into more productive 'modern' sectors of the economy. And while the relationship between GDP per capita and industry's share of production is not as strong as between GDP per capita and agriculture's share, the process of industrialisation has generally been continuing in our region in recent decades (Chart 4).

Chart 4: Industry's share of total production vs GDP per capita (1980-2009)

Source: World Bank World Development Indicator.

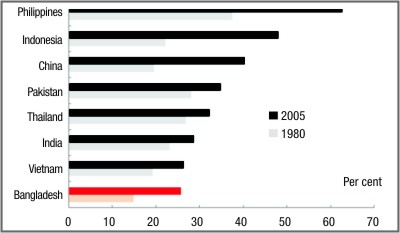

Indeed, Bangladesh seems to industrialising earlier than its richer neighbours like India and Pakistan. At nearly a third in 2009, industry's share of total production was higher in Bangladesh (GDP per capita of $1,300) than in India (GDP per capita of $3,000) and Pakistan (GDP per capita of $2,350). This partly reflects India's rather unique path to prosperity, which is reliant more on the services than industry.2 But from Chart 4 it is evident that Bangladesh is industrialising rapidly relative to its stage of development. The problem, however, is with the productivity in the country's industry sector -- between 1996 and 2005, it fell (Chart 5)! Given the complete lack of any discussion on productivity during last year's debate on the wage award in the garments industry, one cannot be too optimistic about productivity trends since 2005.3

Chart 5: Output per worker in the industry sector

Source: World Bank World Development Indicator, author's calculation.

The government's policy aspiration is to accelerate the industrialisation process such that, by 2021, industry accounts for two-fifths of total production in the economy. To this end, in the 2010-11 Budget, the Government projected a major investment boom that is slated to see the investment-to-GDP ratio rise by over 6 percentage points by 2014-15. Given poor infrastructure, cumbersome regulation, lack of skilled workers and manifold other issues, one can be forgiven for being pessimistic about such an investment boom materialising. 4

However, let's be optimistic and assume that the investment boom of this scale does come to pass. And let's also assume that the resultant industrialisation is accompanied by robust productivity growth in our factories, so that the workers' take home pay rises commensurately, with flow on benefits to the standard of living.

Are we preparing for an industrialised Bangladesh?

Will an industrialised, middle-income Bangladesh also be a more urban Bangladesh? Of course, Bangladesh has become much more urban over the past few decades. The consequences of the unplanned urbanisation of these decades are self-evident to the reader. What might the future hold?

The pace, and type, of urbanisation in our region has varied considerably over the recent decades (Chart 6). In the late 1980s and early 1990s, when industrial output reached about two-fifths of GDP in Indonesia, Thailand and China, less than a third of their people lived in towns and cities. In contrast, India and Pakistan were more urban than Bangladesh during the last decade, despite being less industrialised. Can we learn from Bangkok and Jakarta's experience of traffic management? Do the experiences of pollution in the Chinese cities hold any lesson from us? What can the infrastructure bottleneck in the Indian cities teach us?

Chart 6: Urban population (per cent of total)

Source: World Bank World Development Indicator.

Our budget discussions have a predictable pattern. Incumbent politicians claim the budget to be pro-poor and pro-development. Opposition politicians denounce it as anti-poor and corrupt. Non-partisan pundits question the optimistic development budget and quibble about the deficit financing. Then the year passes. Development programmes are not implemented. Deficit is not so big that financing becomes a problem. There is nothing fundamentally groundbreaking as the government trumpets, but nor does the sky fall as the opposition cries.

This year, can we do something different? Can we discuss some of these long-term, structural issues?

1) In 2005 purchasing power parity terms -- that's the measure used throughout this article.

2) For a good discussion of India's service sector led growth, see: Eichengreen B and Gupta P 2011, The service sector as India's road to economic growth, NBER Working Paper No. 16757.

3) See here: Rahman J, Unanswered questions about the garments wage issue, Forum, October 2010, available at: http://www.thedailystar.net/forum/2010/October/unanswered.htm

4) See here for further discussion on constraints on Bangladesh's economic growth: Rahman J, Perspiration and inspiration, Forum, January 2011, available at: http://www.thedailystar.net/forum/2011/january/perspiration.htm

Jyoti Rahman is an applied macroeconomist and a member of Drishtipat Writers' Collective (www.drishtipat.org/dpwriters) and can be contacted at jyoti.rahman@drishtipat.org.

ANURUP KANTI DAS