|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Volume 7 | Issue 03 | March 2013 | | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Inside

|

Women's Empowerment in Bangladesh: We have achieved major milestones, but much remains to be done, states NEAL WALKER. The Millennium Development Goals (MDG's) are coming to an end in 2015. With the deadline fast approaching, countries are taking stock of their achievements to-date and working hard to ensure the next set of goals reflect core requirements of sustainability and equity. Inclusive and equitable growth1 cannot happen without taking into consideration the role of women -- half of the world's population -- who are also economically and socially most vulnerable. It is crucial that the post-Millennium Development Goals, beyond 2015 (the “Sustainable Development Goals” or SDG's) include, as a core component, women's empowerment and gender equality.2 Bangladesh is an interesting country-case where major milestones have been achieved in women's empowerment and gender equality, particularly in achieving parity in primary education. Yet, much remains to be done. For instance, over 60% of all women continue to face at least one form of violence during their lifespan. By looking at the country specifics, we are able to critically question how representative the MDGs are of the ground realities facing women in developing countries, and Bangladesh in particular. Why is it that Bangladesh has done well on gender-specific targets but the gender aggregates still show poorly? The complexities that plague gender parity in Bangladesh exemplify the global challenge as well: the discussion on how to ensure the SDGs effectively address gender needs to start right now. The Bangladesh Case

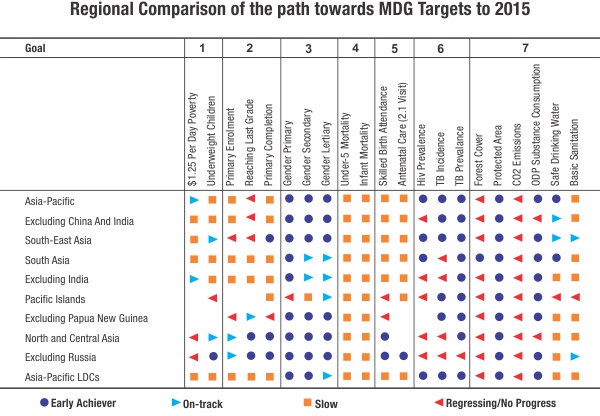

Nationally, the Government of Bangladesh took up the 'education for all' campaign with a strong focus on girl children's education. The stipend programmes for girl children at first in the primary level and then for secondary and higher secondary levels are considered a global best practice that achieved dramatic results in gender parity of education.5 Also important, over the past four decades, the government has implemented targeted social safety net programmes with strong focus on vulnerable women and their families (Morshed, 2009). The conditional cash transfers ensured girls' education especially through specific interventions such as food for work in the Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) programme.6 One of the major milestones in Bangladesh's history in women's empowerment was the enactment of the Local Government (Union Parishad) Second Amendment Act in 1997 that provided for direct elections to reserved seats for women in local level elections. The 6th Five Year Plan (2011-2015) of Bangladesh which is the national medium term development plan committed to transforming Bangladesh into a middle-income country by 2021, considers women's engagement in political and economic activities as a cross-cutting issue with women's empowerment as one of the main drivers of transformation (SFYP 2011-2015). The 6th Five Year Plan coincides with the ending of the MDGs which provides the basis for stock taking on the country's situation so far. Looking at the SFYP on Bangladesh specific situation with the MDGs, the table shows that Bangladesh has achieved gender parity in primary education (Goal 2, Target 1 and Goal 3, Target 1) yet it continues to experience a sharp drop in the number of women entering tertiary education (Goal 3, Target 3.1c). Women's employment in non-agricultural sector is currently around 25% whereas the target is 50%. In another instance, while Bangladesh had done remarkably well in reducing maternal mortality rate by 40% in the last nine years (Maternal Mortality Rate/MMR -194 in 100,000 live births) and is on track for the MDGs of a 75% reduction from 1990-2015, only 24% of all births are attended by skilled health professionals.7 It will be harder to bring down the figure further, without a more comprehensive approach to the problem of maternal mortality. The Gender Inequality Index is also reflective of these continuing challenges which ranked Bangladesh 112 out of 146 in 2011 index in the Human Development Report 2011.8 Based on the indicators, it is important to further explore why Bangladesh, an early achiever and doing very well on certain gender empowerment targets, is now moving at slower pace in critical growth triggering targets such as labour market participation and women's education in tertiary sector. Why is it that with strong pro-women laws and policies, a comparatively small portion of Bangladeshi women is joining local/national politics? Educate a woman, educate a nation Bangladesh was the first country in South Asia to achieve gender-parity in primary education. Achieving this milestone is a result of effective public policy, resource allocation and strong commitment from public and non-government sectors. Yet, education has not been the 'magic bullet' we have long depended on to create a level playing field for women in the developing world. As we see in the case of Bangladesh, social stigmas, gender-based violence and institutional barriers to entering higher education institutions and labour market constraints are holding women back from continuing with their education. Through our various programmatic interventions as well as established literature, we hear accounts of “just enough” education for girls needed for the marriage market. Girls can be pulled out of school by secondary education for the fear of being “too educated” for prospective grooms (Amin and Huq, 2008). Sexual harassments of girl children on their way to school or at school are serious barriers to access to education. In recent times, the alarming number of suicides committed by young girls shook the nation, questioning the safety and security of girls attending school and colleges. Once in school, girl children are seen to miss out on school days because of lack of adequate toilet facilities. Very few activities are available to girl children in schools. Several NGOs are setting up youth clubs, creating spaces for especially for adolescent girls to take part in extra-curricular activities but these are located in specific target areas and not available to the full youth population of Bangladesh. In general, while government and other stakeholders have done an excellent job in getting girls to go to school, we have not created women/girl friendly schools and communities that would encourage and retain girls in school. With the sharp decline in girls in secondary and tertiary education, we see a significant gap in the work force when comparing men and women and their employment opportunities and patterns. While the country is heavily dependent on women's participation in the ready-made garments (RMG) sector and majority of the micro-financing is going to women, the range of occupations available to women remains limited and gender stereotyped. The majority of urban poor women are engaged in the informal sector without basic healthcare or even earning minimum wage. Rural women continue to support their families in agro-and/or non-agro productions that are usually deemed “fitting” by their spouses and families. The next set of international goals therefore, would need to take into account of the non-economic factors that determine girl children's access to education and women's (limited) choices in the workforce. Saving every mother But a vast majority of mothers in Bangladesh are in fact below 18 years of age. Early marriage is intricately connected to issues of safety and security for women and is still widely practised in Bangladesh both in urban and rural areas. Strict laws forbid daughters to be married before the age of 18 but in the absence of birth certificates, girls are married off as early as 14-15 and become first-time mothers by the time they are 16-17. Many young women understand their bodies and ailments for the first time through their pregnancies. There is very little space for women to share their health concerns with either doctors or within their families which results in further complications. There is a social issue of 'modesty' on the part of Bangladeshi women to talk to doctors, especially male physicians. There is a serious demand for female doctors especially in the rural areas where women have little to no access to healthcare. MDG 5 -- Improved Maternal Health -- does take into consideration the non-medical factors that determine the accessibility of healthcare for women in the developing world but it falls short by acting as a proxy for women's access to healthcare in general. Not all medical problems that women face are gynecological in nature. Lower calorie and nutrient intakes of girl children and women due to certain household norms and practices lead to various health concerns that may or may not be related to maternal health. Healthcare and services for women therefore must be looked at from a broader spectrum in the coming years, where women are given the space to freely share their health concerns and receive the proper care. While restricting any discussion on women's health to maternal health was important for a certain goal, in the post-MDG era, we must be able to address health care for women in a more comprehensive, well-being approach. Women's rights are human rights In the last general election, out of the 69 female members of parliament (MPs), 50 were appointed through reserved seats and 19 directly elected, including the Prime Minister and Leader of Opposition. While it is imperative to ensure reserved seats for women in the national parliament, female MPs have voiced their concerns on the lack of election financing and overall party support.9 We find similar stories of work place discrimination from female officers, holding various posts in the government. The rising number of female officers in the public sector is highly encouraging but lack of institutional support for their career development leads to demotivation, early retirement and delayed appointments to decision-making positions. It is a general misconception that with the rise of women's representation in public offices, there will be women's empowerment for both the female representatives/officers and citizens. There is a clear need for more women in public offices but without orientation on gender parity and the roles and responsibilities of each and every representative and officers at both local and national levels, women's empowerment will be difficult to achieve and sustain in the long run. On the flip side, while it is imperative for female (and male) representatives to know their roles and responsibilities as public figures, it is equally important for women in Bangladesh to be well versed in their rights as citizens to demand legitimate services from their political representatives. Bangladeshi women are avid participants at national voting but often shy away from engaging in public and political debates, allowing their husbands to represent their concerns. In this way, women remain separated from the public dialogues and the policymaking process, resulting in gender blind national laws and policies, and in many instances, is discriminatory against women. In short, women's political participation is at the crux of their rights as citizens and must be encouraged in the larger governance process of the country. Beyond MDGs 1.Equitable growth that takes into account of inclusiveness, is a concept that encompasses equity, equality of opportunity, and protection in market and employment transitions (Growth Report, Commission on Growth and Development, 2008) Neal Walker is United Nations Resident Coordinator for Bangladesh. |

||||||||||||||||||||||