| |

Paying

More to get Less

SHAMIM AHSAN

Our

kitchen markets seem to be forever in the grips of the

price monster. Come Ramzan this fiend takes on huge

proportions, shooting up the prices of essential food

items and making the lives of ordinary people more miserable.

But does this phenomenon of price spiral of essentials

inevitable? If yes, why? If not, who is responsible?

Tofazzal

Hossain and his four-year-old daughter Parul hold up

their hands together to say doa as the Magrib Azan wafts

into their 10ft by 8ft room. The mother hurriedly enters

the room with a bottle of cold water. They sit on the

bed forming a circle with a medium sized bowl in the

middle for iftar. The menu can't be simpler -- a mixture

of some pyaju, boot and muri. A few pieces of khejur

(dates) on a separate plate are clearly the special

attraction of today's iftar. Tofazzal

Hossain and his four-year-old daughter Parul hold up

their hands together to say doa as the Magrib Azan wafts

into their 10ft by 8ft room. The mother hurriedly enters

the room with a bottle of cold water. They sit on the

bed forming a circle with a medium sized bowl in the

middle for iftar. The menu can't be simpler -- a mixture

of some pyaju, boot and muri. A few pieces of khejur

(dates) on a separate plate are clearly the special

attraction of today's iftar.

“Parul

has been hankering for dates for the last two days,”

Tofazzal says shyly. A security guard of a fivestoried

building in Gopibagh, with a monthly salary of Tk 3,500,Tofazzal

cannot afford to buy even 250 gm of dates everyday.

“We

don't make iftar at home, it's too expensive,”says Tofazzal's

wife Momotaz who works in 3 houses as a chuta bua.“

How could we when 1 kg of soybean oil sells at Tk. 52.

Iftar is not for the likes of us,” Tofazzal adds. Tofazzal

is not alone in thinking this way. With the wild spiraling

of prices of almost all essential food items during

the Ramadan, breaking the fast with a variety of tasty

tidbits or a wholesome meal, is a far cry.

Ramadan

and price hikes of the essentials have become synonymous.

The only difference this year is that the prices are

increasing at a faster rate and started to spiral much

earlier than usual. Ramadan was still three weeks away

when suddenly the prices started to rocket in the kitchen

market with a record high in the price of onion. Onions

being an integral part of Bangladeshi cooking and regarded

as an 'essential', are a good indicator of what's happening

in the market.

Usually,

the price of onion ranges between Tk 8 and 15 per kg,

depending on the season. But from the second week of

October, the price of onion shot to Tk 32 per kg. Very

soon prices of other food items followed suit. In the

last 2 weeks preceding the Ramadan prices of lentils,

oil, dry chilly, ginger, garlic, meat, powder milk,

vegetables and boot (gram) have increased by Tk 4 to

Tk 25 per kg. As the Ramadan was approaching, prices

of the traditional iftar items also showed marked rise.

Prices of khorma (dry date) rose from Tk 100 to 120,

dates from Tk 38 to Tk 40, muri from Tk 26 to Tk 28

dabli motor (chickpeas) from Tk 18 to 20, baisan from

20 to 24. Beside, prices of each kg of gram increased

Tk 6 to 8 and of chira by Tk 2 to Tk 4. The list doesn't

end here. Prices of vegetables and fruits have also

been souring and out of the reach of the low income

group people, who with their fixed income are being

forced to cut off or lessen the different essential

food items from their daily menu. Zamila Begum, a widow

who lives with her daughter and her son-in-law and works

as a domestic maid, says that she hasn't had fish for

months and even vegetables are too pricey. Her family

eats iftar together, a meal of just rice and lentils. Usually,

the price of onion ranges between Tk 8 and 15 per kg,

depending on the season. But from the second week of

October, the price of onion shot to Tk 32 per kg. Very

soon prices of other food items followed suit. In the

last 2 weeks preceding the Ramadan prices of lentils,

oil, dry chilly, ginger, garlic, meat, powder milk,

vegetables and boot (gram) have increased by Tk 4 to

Tk 25 per kg. As the Ramadan was approaching, prices

of the traditional iftar items also showed marked rise.

Prices of khorma (dry date) rose from Tk 100 to 120,

dates from Tk 38 to Tk 40, muri from Tk 26 to Tk 28

dabli motor (chickpeas) from Tk 18 to 20, baisan from

20 to 24. Beside, prices of each kg of gram increased

Tk 6 to 8 and of chira by Tk 2 to Tk 4. The list doesn't

end here. Prices of vegetables and fruits have also

been souring and out of the reach of the low income

group people, who with their fixed income are being

forced to cut off or lessen the different essential

food items from their daily menu. Zamila Begum, a widow

who lives with her daughter and her son-in-law and works

as a domestic maid, says that she hasn't had fish for

months and even vegetables are too pricey. Her family

eats iftar together, a meal of just rice and lentils.

Most

people are not interested in the pros and cons of the

tricky question of why prices are soaring this way.

The easiest answer by condemning the government. “It

is the government's responsibility to keep prices of

essentials in check, but they are busy fattening their

coffer,” Rasheduddin, a security guard working for Group

4, says bitterly. He reveals that his monthly food charge

in the mess, where he lives with two of his co-workers,

has already surpassed the usual Tk 800 per month though

there are still 5 or 6 days to go. Saiful Islam, a second

class employee in the main branch of Bangladesh Krishi

Bank, also refuses to analyse who the real culprit is

and to what degree others have contributed to this unbearable

market condition. “I don't care who are responsible.

I just want to see an end to it,” he says impatiently.

“Now, as potato is selling at Tk 14 a kg even rice and

alu bharta seem to be going beyond the reach of people

like us,” Islam says. “It has been almost a month since

prices have been increasing rapidly, but the government

hasn't done anything at all. Why doesn't it take actions

against those who are creating such situations?” says

Biplob, another shopper at the vegetables market in

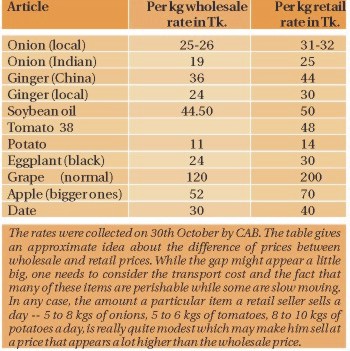

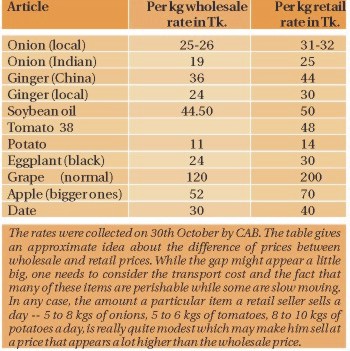

Gopibagh. When it comes to finding why prices are increasingly

this way or who is/are responsible for it there are

various theories. Some reports in various newspapers

point to the big gap between wholesale and retail prices

and in doing so hold the retailers largely responsible

for price hike. But it may not be as simple as that. Most

people are not interested in the pros and cons of the

tricky question of why prices are soaring this way.

The easiest answer by condemning the government. “It

is the government's responsibility to keep prices of

essentials in check, but they are busy fattening their

coffer,” Rasheduddin, a security guard working for Group

4, says bitterly. He reveals that his monthly food charge

in the mess, where he lives with two of his co-workers,

has already surpassed the usual Tk 800 per month though

there are still 5 or 6 days to go. Saiful Islam, a second

class employee in the main branch of Bangladesh Krishi

Bank, also refuses to analyse who the real culprit is

and to what degree others have contributed to this unbearable

market condition. “I don't care who are responsible.

I just want to see an end to it,” he says impatiently.

“Now, as potato is selling at Tk 14 a kg even rice and

alu bharta seem to be going beyond the reach of people

like us,” Islam says. “It has been almost a month since

prices have been increasing rapidly, but the government

hasn't done anything at all. Why doesn't it take actions

against those who are creating such situations?” says

Biplob, another shopper at the vegetables market in

Gopibagh. When it comes to finding why prices are increasingly

this way or who is/are responsible for it there are

various theories. Some reports in various newspapers

point to the big gap between wholesale and retail prices

and in doing so hold the retailers largely responsible

for price hike. But it may not be as simple as that.

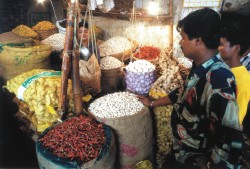

Yasin

Mollah, a stout middle-aged, retail seller of onion,

garlic, ginger, dry chilly and lentils at Gopibagh bazaar

intently looks at his daily accounts. When he is asked

the question the entire nation is asking he grows a

bit glum: “Bhai, it is very easy to accuse the poor

sellers like us. But I cannot sell things at lesser

prices than I have bought at.” Mollah gives examples.

“The wholesale price of the Indian onions is Tk 20 to

Tk 22 depending on qualities at Shambazaar. Add to that

the transport cost, the rent of this is Tk 1500 a month

and also the sizable amount we lose as onions rot very

quickly. Now tell me if I am asking too much,” he demands.

On 30th October he was selling Indian onions at Tk 26/27. Yasin

Mollah, a stout middle-aged, retail seller of onion,

garlic, ginger, dry chilly and lentils at Gopibagh bazaar

intently looks at his daily accounts. When he is asked

the question the entire nation is asking he grows a

bit glum: “Bhai, it is very easy to accuse the poor

sellers like us. But I cannot sell things at lesser

prices than I have bought at.” Mollah gives examples.

“The wholesale price of the Indian onions is Tk 20 to

Tk 22 depending on qualities at Shambazaar. Add to that

the transport cost, the rent of this is Tk 1500 a month

and also the sizable amount we lose as onions rot very

quickly. Now tell me if I am asking too much,” he demands.

On 30th October he was selling Indian onions at Tk 26/27.

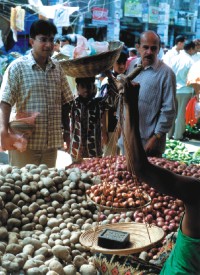

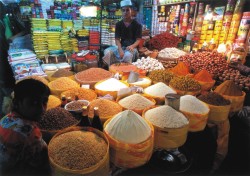

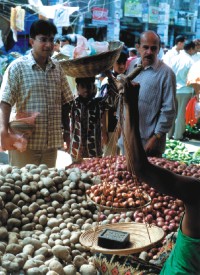

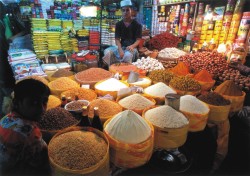

Shambazaar,

the biggest wholesale market for spices, vegetables

and fish, stands along with the Buriganga. Inside the

scores of quite large shops known as aarat sacks filled

with onions, garlic, ginger are stacked neatly. The

long rows of trucks standing almost in the middle of

the road are being unloaded. The large sacks are then

weighed in the giant scale under the close scrutiny

of the aarat manager.

Shouting

of the labourers from all around mixing with the roaring

from the tired engines of the trucks create the soundscape

of Shambazaar, noisy but characteristic of the place.

Retail

sellers do not usually buy from the aarat. There are

wholesale shops a little further down the road who buy

goods in sacks and then sell them to the retailers in

pallas. Each palla is equivalent to 5kg. Enamul Mia,

one of the wholesale businessmen, is seen spreading

out onions across his tiny 4ft by 6ft place. Onions

tend to rot in the damp weather, he says. When he is

asked about their role in pushing up the price of onions

and other things Enamul doesn't protest. Instead he

explains how things happen in the wholesale business:

“My selling price is higher by Tk 1 per palla from my

buying price. Besides there is no scope to lie about

my buying price because buyers (that is the retailers)

come to us after checking with the aaratdar.” The aaratdar

in his turn does business on commission. In the case

of spices an aaratdar gets 30 paisa per every kg sold.

“So it is of no consequence if we sell something at

Tk 20 or Tk 50 per kg,” Khairuzzaman, an aaratdar in

Shambazaar, says. When asked about the allegation labelled

against them that they stock up goods to create crisis

he protests : “ We can sell things at whatever prices

we want. We cannot sell it except at the price fixed

by the importer who is owner of the goods.” One widely

believed theory regarding the suspicious price hikes

has been that of goods being stocked for longer periods

to create an artificial crisis. Majed Mia, an importer

who also owns Raj Traders, an Aarat, in Shambazaar,

scoffs at such an idea. “If I keep onions for more than

3 to 4 days they will start rotting” he says after pointing

to the stacked onions. Besides the earlier I sell the

better price I will get, he adds. Then why did the price

of onions shoot up to Tk 32 per kg? “Because the supply

was much lower than the demand,” he reasons. Normally

it takes 5 to 6 days to get things from Kolkata to Dhaka.

But sometimes rush in the borders or delay in custom

formalities take up extra time.” Other factors are at

work too. “Often we cannot sell onions or garlic of

the same shipment (chalan) at the same price; by the

time we receive them, a large amount has lost its original

freshness.” Retail

sellers do not usually buy from the aarat. There are

wholesale shops a little further down the road who buy

goods in sacks and then sell them to the retailers in

pallas. Each palla is equivalent to 5kg. Enamul Mia,

one of the wholesale businessmen, is seen spreading

out onions across his tiny 4ft by 6ft place. Onions

tend to rot in the damp weather, he says. When he is

asked about their role in pushing up the price of onions

and other things Enamul doesn't protest. Instead he

explains how things happen in the wholesale business:

“My selling price is higher by Tk 1 per palla from my

buying price. Besides there is no scope to lie about

my buying price because buyers (that is the retailers)

come to us after checking with the aaratdar.” The aaratdar

in his turn does business on commission. In the case

of spices an aaratdar gets 30 paisa per every kg sold.

“So it is of no consequence if we sell something at

Tk 20 or Tk 50 per kg,” Khairuzzaman, an aaratdar in

Shambazaar, says. When asked about the allegation labelled

against them that they stock up goods to create crisis

he protests : “ We can sell things at whatever prices

we want. We cannot sell it except at the price fixed

by the importer who is owner of the goods.” One widely

believed theory regarding the suspicious price hikes

has been that of goods being stocked for longer periods

to create an artificial crisis. Majed Mia, an importer

who also owns Raj Traders, an Aarat, in Shambazaar,

scoffs at such an idea. “If I keep onions for more than

3 to 4 days they will start rotting” he says after pointing

to the stacked onions. Besides the earlier I sell the

better price I will get, he adds. Then why did the price

of onions shoot up to Tk 32 per kg? “Because the supply

was much lower than the demand,” he reasons. Normally

it takes 5 to 6 days to get things from Kolkata to Dhaka.

But sometimes rush in the borders or delay in custom

formalities take up extra time.” Other factors are at

work too. “Often we cannot sell onions or garlic of

the same shipment (chalan) at the same price; by the

time we receive them, a large amount has lost its original

freshness.”

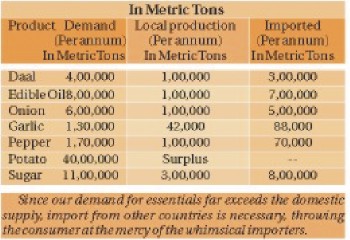

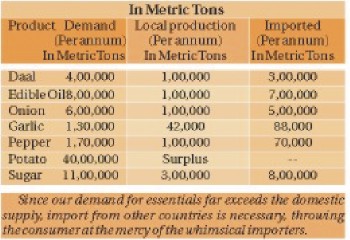

If

we closely examine the ways retail or wholesale business

works it is clear that they simply don't have much control

of the market. It is only the importers who have the

means and scope to manipulate the market. Because it

is the importers who set the price in the first place.

Sometimes before they finish a particular chalan prices

go up in the country from where the goods were imported.

They immediately raise the price though they are actually

selling from the same chalan. Sometimes they intentionally

make delays in placing orders or keep stocks for longer

periods than they should to create an artificial crisis.

“Sometimes they exploit their own created crisis to

force the government to withdraw taxes on imported goods

to multiply their profit,” he explains. Maleque alludes

to a 'plot' of the edible oil importers who are lobbying

with the government so that it lifts taxes despite the

fact that they already have millions of tonnes in their

stocks that were bought at Tk 39 to Tk 41 with the L/C

opened in July-August. If

we closely examine the ways retail or wholesale business

works it is clear that they simply don't have much control

of the market. It is only the importers who have the

means and scope to manipulate the market. Because it

is the importers who set the price in the first place.

Sometimes before they finish a particular chalan prices

go up in the country from where the goods were imported.

They immediately raise the price though they are actually

selling from the same chalan. Sometimes they intentionally

make delays in placing orders or keep stocks for longer

periods than they should to create an artificial crisis.

“Sometimes they exploit their own created crisis to

force the government to withdraw taxes on imported goods

to multiply their profit,” he explains. Maleque alludes

to a 'plot' of the edible oil importers who are lobbying

with the government so that it lifts taxes despite the

fact that they already have millions of tonnes in their

stocks that were bought at Tk 39 to Tk 41 with the L/C

opened in July-August.

By

forming trade associations like onion importers' association

or dal importers' association, these importers cum businessmen

have established such absolute control over the market

that the government play hostage in their hands.,” points

out Emdad Hossain Maleque, Programme Officer, Research

and Information Cell, Consumers' Association of Bangladesh

(CAB).

“And

it is the wrong policy of the government that has given

these greedy dishonest businessmen the scope to exploit

the situation to their advantage,” he adds. In the name

of free market economy the government (who is not supposed

to either intervene or influence the market) has made

people dependent, for many of the essential food items,

on the business people. “And

it is the wrong policy of the government that has given

these greedy dishonest businessmen the scope to exploit

the situation to their advantage,” he adds. In the name

of free market economy the government (who is not supposed

to either intervene or influence the market) has made

people dependent, for many of the essential food items,

on the business people.

If

a section of businessmen are behind the price spiral

the government is guilty of letting them go unchallenged.

Inspite of the continuous media uproar Commerce Minister

Amir Khosru Mahmud Chowdhury chose to ignore the whole

issue uttering what seems to be his dearest doctrine

: “ In a free market economy prices are determined by

the market force, the Government cannot control it.”

He however had to eat his words when the Government

cut down 29% tariff on onions to 7%. Why didn't the

government do this earlier? Don't they know there are

price hikes during every Ramadan?” Mizanur Rahman, a

doctor working at the Monowara Hospital, wonders.

The

reason the government couldn't act on time is because

it doesn't have any mechanism to monitor the market

and get up--to--date information about the demand and

supply of various items, day to day retail or wholesale

market price, market prices in the country from where

goods are being imported, transportation costs, approximate

time period for transport and other related issues,

so that it can work out a reasonable price policy and

then bargain with the business people, Maleque suggests.

Such information would give the Government the opportunity

to pre-judge the market condition and take measures

accordingly. The government moreover, must have a substitute

arrangement ready so that it can import during emergency

situations. The government can easily use the TCB (Trading

Corporation of Bangladesh) for this purpose. The

reason the government couldn't act on time is because

it doesn't have any mechanism to monitor the market

and get up--to--date information about the demand and

supply of various items, day to day retail or wholesale

market price, market prices in the country from where

goods are being imported, transportation costs, approximate

time period for transport and other related issues,

so that it can work out a reasonable price policy and

then bargain with the business people, Maleque suggests.

Such information would give the Government the opportunity

to pre-judge the market condition and take measures

accordingly. The government moreover, must have a substitute

arrangement ready so that it can import during emergency

situations. The government can easily use the TCB (Trading

Corporation of Bangladesh) for this purpose.

Whatever

is said about a 'free market economy,' the Government

cannot shrug off its responsibility and must do everything

necessary to bring back normalcy in the market. But

for that general people need to be aware of their rights

as consumers so that they can make the government perform

its duties in this regard.

|

|

Tofazzal

Hossain and his four-year-old daughter Parul hold up

their hands together to say doa as the Magrib Azan wafts

into their 10ft by 8ft room. The mother hurriedly enters

the room with a bottle of cold water. They sit on the

bed forming a circle with a medium sized bowl in the

middle for iftar. The menu can't be simpler -- a mixture

of some pyaju, boot and muri. A few pieces of khejur

(dates) on a separate plate are clearly the special

attraction of today's iftar.

Tofazzal

Hossain and his four-year-old daughter Parul hold up

their hands together to say doa as the Magrib Azan wafts

into their 10ft by 8ft room. The mother hurriedly enters

the room with a bottle of cold water. They sit on the

bed forming a circle with a medium sized bowl in the

middle for iftar. The menu can't be simpler -- a mixture

of some pyaju, boot and muri. A few pieces of khejur

(dates) on a separate plate are clearly the special

attraction of today's iftar.  Usually,

the price of onion ranges between Tk 8 and 15 per kg,

depending on the season. But from the second week of

October, the price of onion shot to Tk 32 per kg. Very

soon prices of other food items followed suit. In the

last 2 weeks preceding the Ramadan prices of lentils,

oil, dry chilly, ginger, garlic, meat, powder milk,

vegetables and boot (gram) have increased by Tk 4 to

Tk 25 per kg. As the Ramadan was approaching, prices

of the traditional iftar items also showed marked rise.

Prices of khorma (dry date) rose from Tk 100 to 120,

dates from Tk 38 to Tk 40, muri from Tk 26 to Tk 28

dabli motor (chickpeas) from Tk 18 to 20, baisan from

20 to 24. Beside, prices of each kg of gram increased

Tk 6 to 8 and of chira by Tk 2 to Tk 4. The list doesn't

end here. Prices of vegetables and fruits have also

been souring and out of the reach of the low income

group people, who with their fixed income are being

forced to cut off or lessen the different essential

food items from their daily menu. Zamila Begum, a widow

who lives with her daughter and her son-in-law and works

as a domestic maid, says that she hasn't had fish for

months and even vegetables are too pricey. Her family

eats iftar together, a meal of just rice and lentils.

Usually,

the price of onion ranges between Tk 8 and 15 per kg,

depending on the season. But from the second week of

October, the price of onion shot to Tk 32 per kg. Very

soon prices of other food items followed suit. In the

last 2 weeks preceding the Ramadan prices of lentils,

oil, dry chilly, ginger, garlic, meat, powder milk,

vegetables and boot (gram) have increased by Tk 4 to

Tk 25 per kg. As the Ramadan was approaching, prices

of the traditional iftar items also showed marked rise.

Prices of khorma (dry date) rose from Tk 100 to 120,

dates from Tk 38 to Tk 40, muri from Tk 26 to Tk 28

dabli motor (chickpeas) from Tk 18 to 20, baisan from

20 to 24. Beside, prices of each kg of gram increased

Tk 6 to 8 and of chira by Tk 2 to Tk 4. The list doesn't

end here. Prices of vegetables and fruits have also

been souring and out of the reach of the low income

group people, who with their fixed income are being

forced to cut off or lessen the different essential

food items from their daily menu. Zamila Begum, a widow

who lives with her daughter and her son-in-law and works

as a domestic maid, says that she hasn't had fish for

months and even vegetables are too pricey. Her family

eats iftar together, a meal of just rice and lentils. Most

people are not interested in the pros and cons of the

tricky question of why prices are soaring this way.

The easiest answer by condemning the government. “It

is the government's responsibility to keep prices of

essentials in check, but they are busy fattening their

coffer,” Rasheduddin, a security guard working for Group

4, says bitterly. He reveals that his monthly food charge

in the mess, where he lives with two of his co-workers,

has already surpassed the usual Tk 800 per month though

there are still 5 or 6 days to go. Saiful Islam, a second

class employee in the main branch of Bangladesh Krishi

Bank, also refuses to analyse who the real culprit is

and to what degree others have contributed to this unbearable

market condition. “I don't care who are responsible.

I just want to see an end to it,” he says impatiently.

“Now, as potato is selling at Tk 14 a kg even rice and

alu bharta seem to be going beyond the reach of people

like us,” Islam says. “It has been almost a month since

prices have been increasing rapidly, but the government

hasn't done anything at all. Why doesn't it take actions

against those who are creating such situations?” says

Biplob, another shopper at the vegetables market in

Gopibagh. When it comes to finding why prices are increasingly

this way or who is/are responsible for it there are

various theories. Some reports in various newspapers

point to the big gap between wholesale and retail prices

and in doing so hold the retailers largely responsible

for price hike. But it may not be as simple as that.

Most

people are not interested in the pros and cons of the

tricky question of why prices are soaring this way.

The easiest answer by condemning the government. “It

is the government's responsibility to keep prices of

essentials in check, but they are busy fattening their

coffer,” Rasheduddin, a security guard working for Group

4, says bitterly. He reveals that his monthly food charge

in the mess, where he lives with two of his co-workers,

has already surpassed the usual Tk 800 per month though

there are still 5 or 6 days to go. Saiful Islam, a second

class employee in the main branch of Bangladesh Krishi

Bank, also refuses to analyse who the real culprit is

and to what degree others have contributed to this unbearable

market condition. “I don't care who are responsible.

I just want to see an end to it,” he says impatiently.

“Now, as potato is selling at Tk 14 a kg even rice and

alu bharta seem to be going beyond the reach of people

like us,” Islam says. “It has been almost a month since

prices have been increasing rapidly, but the government

hasn't done anything at all. Why doesn't it take actions

against those who are creating such situations?” says

Biplob, another shopper at the vegetables market in

Gopibagh. When it comes to finding why prices are increasingly

this way or who is/are responsible for it there are

various theories. Some reports in various newspapers

point to the big gap between wholesale and retail prices

and in doing so hold the retailers largely responsible

for price hike. But it may not be as simple as that. Yasin

Mollah, a stout middle-aged, retail seller of onion,

garlic, ginger, dry chilly and lentils at Gopibagh bazaar

intently looks at his daily accounts. When he is asked

the question the entire nation is asking he grows a

bit glum: “Bhai, it is very easy to accuse the poor

sellers like us. But I cannot sell things at lesser

prices than I have bought at.” Mollah gives examples.

“The wholesale price of the Indian onions is Tk 20 to

Tk 22 depending on qualities at Shambazaar. Add to that

the transport cost, the rent of this is Tk 1500 a month

and also the sizable amount we lose as onions rot very

quickly. Now tell me if I am asking too much,” he demands.

On 30th October he was selling Indian onions at Tk 26/27.

Yasin

Mollah, a stout middle-aged, retail seller of onion,

garlic, ginger, dry chilly and lentils at Gopibagh bazaar

intently looks at his daily accounts. When he is asked

the question the entire nation is asking he grows a

bit glum: “Bhai, it is very easy to accuse the poor

sellers like us. But I cannot sell things at lesser

prices than I have bought at.” Mollah gives examples.

“The wholesale price of the Indian onions is Tk 20 to

Tk 22 depending on qualities at Shambazaar. Add to that

the transport cost, the rent of this is Tk 1500 a month

and also the sizable amount we lose as onions rot very

quickly. Now tell me if I am asking too much,” he demands.

On 30th October he was selling Indian onions at Tk 26/27. Retail

sellers do not usually buy from the aarat. There are

wholesale shops a little further down the road who buy

goods in sacks and then sell them to the retailers in

pallas. Each palla is equivalent to 5kg. Enamul Mia,

one of the wholesale businessmen, is seen spreading

out onions across his tiny 4ft by 6ft place. Onions

tend to rot in the damp weather, he says. When he is

asked about their role in pushing up the price of onions

and other things Enamul doesn't protest. Instead he

explains how things happen in the wholesale business:

“My selling price is higher by Tk 1 per palla from my

buying price. Besides there is no scope to lie about

my buying price because buyers (that is the retailers)

come to us after checking with the aaratdar.” The aaratdar

in his turn does business on commission. In the case

of spices an aaratdar gets 30 paisa per every kg sold.

“So it is of no consequence if we sell something at

Tk 20 or Tk 50 per kg,” Khairuzzaman, an aaratdar in

Shambazaar, says. When asked about the allegation labelled

against them that they stock up goods to create crisis

he protests : “ We can sell things at whatever prices

we want. We cannot sell it except at the price fixed

by the importer who is owner of the goods.” One widely

believed theory regarding the suspicious price hikes

has been that of goods being stocked for longer periods

to create an artificial crisis. Majed Mia, an importer

who also owns Raj Traders, an Aarat, in Shambazaar,

scoffs at such an idea. “If I keep onions for more than

3 to 4 days they will start rotting” he says after pointing

to the stacked onions. Besides the earlier I sell the

better price I will get, he adds. Then why did the price

of onions shoot up to Tk 32 per kg? “Because the supply

was much lower than the demand,” he reasons. Normally

it takes 5 to 6 days to get things from Kolkata to Dhaka.

But sometimes rush in the borders or delay in custom

formalities take up extra time.” Other factors are at

work too. “Often we cannot sell onions or garlic of

the same shipment (chalan) at the same price; by the

time we receive them, a large amount has lost its original

freshness.”

Retail

sellers do not usually buy from the aarat. There are

wholesale shops a little further down the road who buy

goods in sacks and then sell them to the retailers in

pallas. Each palla is equivalent to 5kg. Enamul Mia,

one of the wholesale businessmen, is seen spreading

out onions across his tiny 4ft by 6ft place. Onions

tend to rot in the damp weather, he says. When he is

asked about their role in pushing up the price of onions

and other things Enamul doesn't protest. Instead he

explains how things happen in the wholesale business:

“My selling price is higher by Tk 1 per palla from my

buying price. Besides there is no scope to lie about

my buying price because buyers (that is the retailers)

come to us after checking with the aaratdar.” The aaratdar

in his turn does business on commission. In the case

of spices an aaratdar gets 30 paisa per every kg sold.

“So it is of no consequence if we sell something at

Tk 20 or Tk 50 per kg,” Khairuzzaman, an aaratdar in

Shambazaar, says. When asked about the allegation labelled

against them that they stock up goods to create crisis

he protests : “ We can sell things at whatever prices

we want. We cannot sell it except at the price fixed

by the importer who is owner of the goods.” One widely

believed theory regarding the suspicious price hikes

has been that of goods being stocked for longer periods

to create an artificial crisis. Majed Mia, an importer

who also owns Raj Traders, an Aarat, in Shambazaar,

scoffs at such an idea. “If I keep onions for more than

3 to 4 days they will start rotting” he says after pointing

to the stacked onions. Besides the earlier I sell the

better price I will get, he adds. Then why did the price

of onions shoot up to Tk 32 per kg? “Because the supply

was much lower than the demand,” he reasons. Normally

it takes 5 to 6 days to get things from Kolkata to Dhaka.

But sometimes rush in the borders or delay in custom

formalities take up extra time.” Other factors are at

work too. “Often we cannot sell onions or garlic of

the same shipment (chalan) at the same price; by the

time we receive them, a large amount has lost its original

freshness.” If

we closely examine the ways retail or wholesale business

works it is clear that they simply don't have much control

of the market. It is only the importers who have the

means and scope to manipulate the market. Because it

is the importers who set the price in the first place.

Sometimes before they finish a particular chalan prices

go up in the country from where the goods were imported.

They immediately raise the price though they are actually

selling from the same chalan. Sometimes they intentionally

make delays in placing orders or keep stocks for longer

periods than they should to create an artificial crisis.

“Sometimes they exploit their own created crisis to

force the government to withdraw taxes on imported goods

to multiply their profit,” he explains. Maleque alludes

to a 'plot' of the edible oil importers who are lobbying

with the government so that it lifts taxes despite the

fact that they already have millions of tonnes in their

stocks that were bought at Tk 39 to Tk 41 with the L/C

opened in July-August.

If

we closely examine the ways retail or wholesale business

works it is clear that they simply don't have much control

of the market. It is only the importers who have the

means and scope to manipulate the market. Because it

is the importers who set the price in the first place.

Sometimes before they finish a particular chalan prices

go up in the country from where the goods were imported.

They immediately raise the price though they are actually

selling from the same chalan. Sometimes they intentionally

make delays in placing orders or keep stocks for longer

periods than they should to create an artificial crisis.

“Sometimes they exploit their own created crisis to

force the government to withdraw taxes on imported goods

to multiply their profit,” he explains. Maleque alludes

to a 'plot' of the edible oil importers who are lobbying

with the government so that it lifts taxes despite the

fact that they already have millions of tonnes in their

stocks that were bought at Tk 39 to Tk 41 with the L/C

opened in July-August. “And

it is the wrong policy of the government that has given

these greedy dishonest businessmen the scope to exploit

the situation to their advantage,” he adds. In the name

of free market economy the government (who is not supposed

to either intervene or influence the market) has made

people dependent, for many of the essential food items,

on the business people.

“And

it is the wrong policy of the government that has given

these greedy dishonest businessmen the scope to exploit

the situation to their advantage,” he adds. In the name

of free market economy the government (who is not supposed

to either intervene or influence the market) has made

people dependent, for many of the essential food items,

on the business people. The

reason the government couldn't act on time is because

it doesn't have any mechanism to monitor the market

and get up--to--date information about the demand and

supply of various items, day to day retail or wholesale

market price, market prices in the country from where

goods are being imported, transportation costs, approximate

time period for transport and other related issues,

so that it can work out a reasonable price policy and

then bargain with the business people, Maleque suggests.

Such information would give the Government the opportunity

to pre-judge the market condition and take measures

accordingly. The government moreover, must have a substitute

arrangement ready so that it can import during emergency

situations. The government can easily use the TCB (Trading

Corporation of Bangladesh) for this purpose.

The

reason the government couldn't act on time is because

it doesn't have any mechanism to monitor the market

and get up--to--date information about the demand and

supply of various items, day to day retail or wholesale

market price, market prices in the country from where

goods are being imported, transportation costs, approximate

time period for transport and other related issues,

so that it can work out a reasonable price policy and

then bargain with the business people, Maleque suggests.

Such information would give the Government the opportunity

to pre-judge the market condition and take measures

accordingly. The government moreover, must have a substitute

arrangement ready so that it can import during emergency

situations. The government can easily use the TCB (Trading

Corporation of Bangladesh) for this purpose.