| |

The Lonely Battle

In

the wake of widespread

denationalisation and the eventual

phasing out of the Multi Fibre

Agreement, the rights of workers

are about to become even more

marginalised. Do responsible

trade unions stand a chance?

Mustafa

Zaman

April

23, 2004. The Muktangan of Paltan still looks rain-drenched

from the heavy Baishakhi splash of the morning. At around

four in the afternoon, amidst the sporadic water puddles,

the people flock towards this place; representing different

labour organisations. Most have taken their seats. More

are joining the already present mass, which is slowly

growing in size. The hogla-mats that have been

spread out to cover the wet ground make up the turf

to sit on, the rest of the empty ground is gradually

being taken up by the joining mass who prefer to stand.

These are not the paid-for dummies that one sees in

those huge political rallies, these are labourers from

all sectors gathered to give voice to their own demands.

Their struggle is born out of the common predicament

of factory shut downs and job-losses, which they tackle

on their own terms. April

23, 2004. The Muktangan of Paltan still looks rain-drenched

from the heavy Baishakhi splash of the morning. At around

four in the afternoon, amidst the sporadic water puddles,

the people flock towards this place; representing different

labour organisations. Most have taken their seats. More

are joining the already present mass, which is slowly

growing in size. The hogla-mats that have been

spread out to cover the wet ground make up the turf

to sit on, the rest of the empty ground is gradually

being taken up by the joining mass who prefer to stand.

These are not the paid-for dummies that one sees in

those huge political rallies, these are labourers from

all sectors gathered to give voice to their own demands.

Their struggle is born out of the common predicament

of factory shut downs and job-losses, which they tackle

on their own terms.

Eight labour federations gather for

the first time to test their unity. For them, unity

is the most elusive word; it is also the most sought

after condition. Yet they could only forge a unity in

lieu of the closure of most of the industries, and the

recent lay-off declared in quite a few. In a desperate

bid to raise a voice in favour of their own interest,

eight streams had to collect in one common flow. This

coalition was named -- "Jatyo Shangram Shamannoi

Parishad", meaning the national alliance for co-ordinated

struggle. The leaders of the alliance crowd the small,

unassuming podium. The programme begins without much

formality.

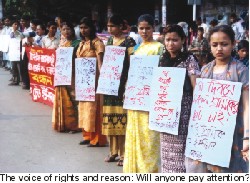

These are desperate moments for thousands

of workers throughout the country. The conspicuously

written placards and festoons cry out "Overturn

the order for pay-off", "Withdraw the order

of lay-off/lay-off at Rangpur Suger Mill", "Restart

the Adamjee Jute Mill" and many more that reveals

a dire picture of the country's industrial landscape.

Later in his address, Shahidullah Chowdhury, the working

president of the Bangladesh Trade Union Centre, gave

a lucid account of the crumbling scenario of the industrial

sector.

"The

number of mills in Bangladesh are diminishing at the

rate at which they are being denationalised," He

said. "There were 78 cotton mills, and now most

of them are closed. There are 18 government owned mills,

out of which 16 are still running. Although IMF, WTO

and many other international organisations are advocating

privatisation, in reality it is not working," Shahidullah

let the crowd know. His data depicts a bleak scenario

of the privatised spinning and cotton mills. Out of

54 privatised ones no one is running. Later in an interview

with SWM, he said, "78 mills were closed off, and

54 of them were denationalised and "The

number of mills in Bangladesh are diminishing at the

rate at which they are being denationalised," He

said. "There were 78 cotton mills, and now most

of them are closed. There are 18 government owned mills,

out of which 16 are still running. Although IMF, WTO

and many other international organisations are advocating

privatisation, in reality it is not working," Shahidullah

let the crowd know. His data depicts a bleak scenario

of the privatised spinning and cotton mills. Out of

54 privatised ones no one is running. Later in an interview

with SWM, he said, "78 mills were closed off, and

54 of them were denationalised and

had seen their demise while in private ownership".

The

alliance of eight federations is fighting against the

tide of the time. Denationalisation is the phrase-turned

'developmental motto' in the present economic matrix,

and the unionists have been orienting themselves against

it. Their resolve to fight this trend that hinges upon

the concept of globalisation is intense. To be able

to raise a voice against it is one thing, but to tackle

the most pressing issue of national interest is a virtual

war in the offing. And this ideological war the unionist

would have to fight alone. With the booming IT related

businesses in sight and the considerable success in

the garment sector, not many are willing to examine

what is happening in the industrial sectors dependent

on indigenous raw materials. While industries that draw

on the cotton, jute and sugarcane produced in our own

soil are being laid off, the impact is twofold, one

is the loss of jobs by the labourers and other, which

has a wider implication, is the impoverishment of the

farmers. Laying-off of industries have hit the producers

of raw materials the hardest. While the industries are

dying, both the producers of raw materials and the labourers

working in mills are finding themselves in between a

rock and a hard place. The former is being forced to

grow something less profitable and the latter are losing

their jobs due to lay-off that is more often a euphemism

for complete shut down. The union of the federations

wants to bring this into sharp focus, and is all set

to combat the trend of denationa-lisation.

Shahidullah

attests to the futility of privatisation and he also

illustrates how the existing multi-organisational platform

SCOP (sramik karmachary aoikyo parishad) is failing

to deal with the real issues, "as the pro-government

labour organisation is always there to wave any action

that opposes the policies taken up by the government."

To be able to escape the noose of '<>dalbaji',

as Shahidullah dubs any pro-party action or inaction

that flouts the interest of the workers, is a humongous

task. The united eight, the forged alliance, is out

to deconstruct the norm of the party-in-power-oriented

unionism that considers workers as mere pawns in keeping

things under the tight grip of the people at the helm.

The

garment sector has an altogether different character.

Yet the lives of the workers in this precinct remain

as volatile as their brethren in others sectors. The

workers are job seekers from the poor hovels, who become

city-bound as resources in the rural areas are decimating

quickly. But, once in the cities, they become another

cog in the great wheel of an industry that so far has

based itself on minimum wage and the 'quota' rewarded

mostly by the USA. The

garment sector has an altogether different character.

Yet the lives of the workers in this precinct remain

as volatile as their brethren in others sectors. The

workers are job seekers from the poor hovels, who become

city-bound as resources in the rural areas are decimating

quickly. But, once in the cities, they become another

cog in the great wheel of an industry that so far has

based itself on minimum wage and the 'quota' rewarded

mostly by the USA.

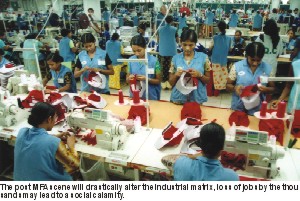

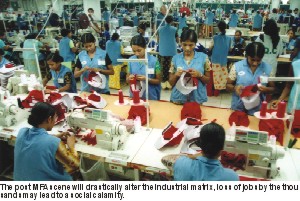

The garment sector can be termed as an assemblage industry.

All materials come from abroad, and the strings of activities

like dying, cutting and sewing that lead to the manufactured

items are part of the process of assembling. And a whole

new workforce has developed along this line. The garment

sector is the epitome of what is termed a labour intensive

industry.

In

2005, after the withdrawal of the Multi Fibre Arrangement

(MFA), the quota system will be no more, and a country

like Bangladesh without its own fibre and fabric is

bound for a nosedive. Shahidullah fears that many garment

factories will meet with demise and a huge number of

workers will be out of jobs. "It is a social calamity

in the waiting," adds Shahidullah gravely.

It

is lamentable how the government could not come up with

any workable strategy to tackle the post MFA situation.

"A taskforce has been formed with government '<>amlas'

as its members, I don't know how it will tackle this

'emergency situation' within eight months. There are

no representatives of the labourers in the taskforce,"

Shahidullah explains how workers are even shunned when

it comes to coping with an imminent disaster that will

effect them the most. "In Sri Lanka they have been

preparing for this for the last two years, and have

developed a huge fund for the labourers," Shahidullah

adds.

It

was during the eighties that Bangladesh jumped into

the bandwagon of the garment manufacturer countries.

"Though the hi-tech boom fuelled it, it was mainly

to cope with the oil boycott by the Arab countries that

the garment sector was deemed redundant in the West.

The machinery of this labour intensive industry was

exported to least developed countries where labour was

cheap," says Shahidullah.

After

more than 15 years it has become a means of gaining

a huge remittance. Shahidullah thinks otherwise., "Only

one third of the total income remains in Bangladesh,

the rest is spent on fibres and clothes" he says.

"It is the 'mojury' -- the wage -- that

remains". He hastens to add, "The quota is

given only for products made with the cheapest labour.

Quota means the payment would be double for the products

and this made the boom possible in Bangladesh".

This is also the reason why a huge labour force remains

in the throes of a well-orchestrated monopoly. According

to experts, MFA itself violates the fundamental principal

of GATT (General Agreement of Trade and Tarrif). It

flouts Article 1 on non-discrimination and Article XI

on abolition of Non-Tariff Barriers. "The discrimination

was destined for developing countries," said Will

Martin at a seminar in the World Bank. According to

Martin, quota often hurts the other industries as "when

one commodity faces quota, resources are likely to be

shifted towards it". This is what happened in Bangladesh.

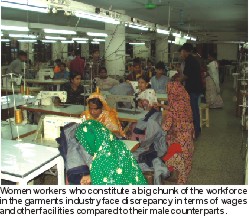

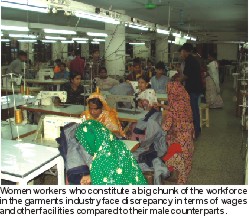

As

cheap labour is the only source of income in this sector,

workers have never been given the status that they deserved.

In the last 18 or so years no proper union have been

allowed to operate to raise awareness about workers'

rights. Today in 3,300 factories situated mainly in

Dhaka, Chittagong, Narayanganj, Savar, Tongi and Gazipur,

a total of 1,320,000 women and 280,000 men are subjected

to the will of the owners. In absence of the law regarding

the national minimum wage, workers stand to lose. There

is this provision for fixing the minimum wage in every

sector, which is to be revised in every three years,

but in reality it has never been implemented, says a

report by the National Garment Workers Federation who

also furnished the present figures of factories and

workers. It also highlights that "in 1994, the

minimum wage for the unskilled labourers was fixed at

Tk. 930 per month, and for the skilled at Tk. 2,300,

but this was not implemented in all sectors". As

cheap labour is the only source of income in this sector,

workers have never been given the status that they deserved.

In the last 18 or so years no proper union have been

allowed to operate to raise awareness about workers'

rights. Today in 3,300 factories situated mainly in

Dhaka, Chittagong, Narayanganj, Savar, Tongi and Gazipur,

a total of 1,320,000 women and 280,000 men are subjected

to the will of the owners. In absence of the law regarding

the national minimum wage, workers stand to lose. There

is this provision for fixing the minimum wage in every

sector, which is to be revised in every three years,

but in reality it has never been implemented, says a

report by the National Garment Workers Federation who

also furnished the present figures of factories and

workers. It also highlights that "in 1994, the

minimum wage for the unskilled labourers was fixed at

Tk. 930 per month, and for the skilled at Tk. 2,300,

but this was not implemented in all sectors".

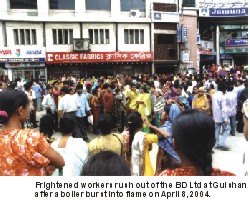

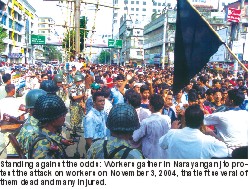

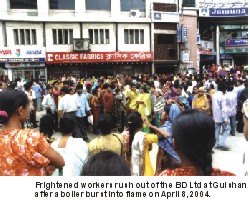

Meanwhile,

several fire incidents took hundreds of lives in last

fifteen years or so. Fire exits had been put up in recent

years, but not a single incident was subject to proper

investigation. Events of sexual abuse and all sorts

of mistreatment are rampant, and they often go unregistered.

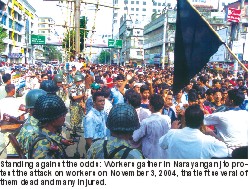

The Narayanganj incident in November 3, at the BSCIC

City that exploded into a virtual battle between the

authorities and the workers is proof of how exploitation

and maltreatment

can backfire.

Yet

till today, there is no fixed salary for the workers

who do the most crucial task of all, -- sewing. Md.

Russel Raihan has been working as sewing operator for

last two years, and had never been employed on a retainer

basis. He says, "I was with the Dynasty Sweater

Ltd. which used to treat the workers better and now

I work for Panta Ltd, where if you become ill and apply

for a leave of seven days you would be lucky to get

permission for two. I receive 300 Taka for every batch

of 12 sweaters I sew".

Young

women make up more then three fourths of the workforce

in this sector. Tanjila is a new recruit at ATS garment

in Kalyanpur. She gets a monthly salary of Tk. 930,

and a 'hajira' bonus of Tk. 100 per month if she shows

up every day. She is happy to make this much as there

are no other options.

Although

there is a rule against letting women workers stay after

eight in the night, in most factories overtime has become

a norm. A worker with a salary of Tk. 1,500 states that

an hour of overtime translates into seven and a half

taka for her. "It depends on the salary you get,

many get even ten an hour," she adds.

Shahidullah

gives us the international scenario, "In the USA,

an hour's income is 13$, in Bangladesh, a garment worker

doesn't even make that in one month". Shahidullah

gives us the international scenario, "In the USA,

an hour's income is 13$, in Bangladesh, a garment worker

doesn't even make that in one month".

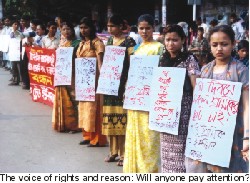

As

for the scenario of workers and their right to have

unions, the garment sector remains a backwater. "Hundreds

of them have lost their jobs trying to work for a union.

We have resorted to the highest court of law but to

no avail. There are more than 3000 factories but you

would not find 50 unions," Shahidullah remarks.

He adds that they have been actively trying to form

unions for the last two years, and have not yet been

successful". "There are about 24 federations,

but they are not really representative of the workers,"

Shahidulla points out.

Meanwhile

the National Garments Workers Federation (NGWF), in

their website mentions 22 federations and three alliances

that are registered and six unregistered federations.

Yet no one could really effect a change. Even the investigation

in the Narayanganj incident had never been completed.

NGWF's website catalogues a number of cases of fire

victims, on behalf of whom they negotiated and helped

get the families the compensation. Many labour organisations'

activities revolve around protest rallies and mourning

precessions. Sometimes they may press for greater issues

like duty and quota-free entry. They also take up the

issue of payment of festival bonus that often go unpaid.

There are also greater issues that no one has been able

to resolve. Campaigns and actions simply did not accrue

much. No one was ready to tackle the situation in 2001

when 1000 factories were closed down leaving 300,000

jobless according to an NGWF estimation. Amirul Haque

Amin, the general secretary of NGWF, held a press conference

at the Topkhana office, as more factories were speeding

towards the same fate, urging the US for quota-free

entry for Bangladeshi items.

With

all the effort from all these organisations the awareness

even to observe May 1st a holiday could not be created.

Even the day that is referred to as the 'garment workers

safety day' to mark the death of 29 workers in Saraka

Garment fire in Mirpur back in 1990, is not observed

as a holiday on a national level. "A list of the

49 garment factories who forced the workers to work

on May Day were submitted to the present government

last year, but the government did not take any measures,"

Amirul said in his address on April 23.

About

the pervasive corruption that ails unionism in other

sectors Shahidullah replies, "Three things stand

in our way, -- one and the most important of all is

'dalbaji', meaning partisan or pro-government party

politics, and the others are opportunism and duplicity,

all born out of the former." He believes that the

true spirit of unionism is based on responsibility.

"Trade unionism is not against the industry or

its profit, it is against maltreatment and inequity.

When the idea of participatory democracy is gaining

ground in the world, you must let labourers partake

on the decision-making mechanism and have a share of

the benefits," Shahidullah argues.

To

cope with the post MFA disaster, the unionist has come

up with a blanket plan. Shahidullah is full with resolve,

he says, "We have placed our suggestion to rejuvenate

the 18 government owned spinning and textile mills.

The infrastructure is there, every factory has the capacity

to accommodate three to four thousand workers. With

the machinery replaced, we can produce our own fabrics

that also has a huge local market. 1000 crore Taka can

change the industrial scene."

M

M Akash, a professor of economics at the Dhaka University,

brackets Bangladesh within the axis of "late Capitalist

Development", which puts a country in the whirlpool

of many forces. One of the strongest, he believes, is

the imperialist intervention. The telltale signs of

a late capitalist country, he detects manifests in the

unskilled labour force, undeveloped energy sources and

infrastructure. In his opinion, these countries are

replete with "labour intensive industries",

as in Bangladesh. But who would waste one's breath in

suggesting the government, which is eternally in debt

to IMF and the World Bank to take a detour from the

regular course set by the donors and restore the government

owned industries? The unionists would, as their life

is at stake.

Lost in Unionism

SHAMIM

AHSAN

It

was 83, Ershad's regime. A Trade Union, based in Fulbaria

bus stand was on strike. Suddenly talks of calling off

the strike were in circulation. Not because the government

had accepted their demands, but because of a deal between

the Union leader and the assigned government officials.

The bargain was that the government would release the

Union leader's brother who was facing a charge of bank

robbery, in exchange of withdrawal of the strike. The

story told by Manzurul Ahsan, President of the Communist

Party of Bangladesh, aptly illustrates the essential

characteristic of the current trade union culture of

the country. It

was 83, Ershad's regime. A Trade Union, based in Fulbaria

bus stand was on strike. Suddenly talks of calling off

the strike were in circulation. Not because the government

had accepted their demands, but because of a deal between

the Union leader and the assigned government officials.

The bargain was that the government would release the

Union leader's brother who was facing a charge of bank

robbery, in exchange of withdrawal of the strike. The

story told by Manzurul Ahsan, President of the Communist

Party of Bangladesh, aptly illustrates the essential

characteristic of the current trade union culture of

the country.

Few would contest that saving a few

exceptions trade unions in general have been a great

failure. Trade unions that are meant to be upholding

the rights of the common workers and fighting for their

cause, have long been turned into an instrument to realise

personal or group interest and in some cases a launching

ground to materialise one's political ambition. There

is a plethora of factors that are responsible for the

failure of trade unions in our country.

The greatest blow for the trade union

came from politics. We are a strange nation, divided

everywhere in the line of political identity. Every

organisation or association, whether they are political

or apolitical in nature is divided into AL and BNP camps.

Associations of university teachers or journalists or

lawyers, which are apolitical in nature and should have

their own agenda, are now acting like front organisations

for different political parties. The same virus infects

trade unions; their names, especially the surnames like

Dal and League, not only suggest their literal association

with the political parties but by means of their activities

show their parasitic existence.

Besides,

in most cases, trade unions, particularly the ones associated

with BNP and AL, do not represent the workers community

in the true sense, claims Dewan Muhammad Ali, President

of Bangladesh Rail Sramik Union and Vice President of

Bangladesh Trade Union Kendro (TUC). Union leaders,

who are supposed to be elected by worker-members of

the union through votes, are often chosen by the party

high ups of the political party they are associated

with. "If a leader is not elected by workers why

should he bother about the workers' welfare as long

as he is in the good

book of his mentors?" Ali explains. Besides,

in most cases, trade unions, particularly the ones associated

with BNP and AL, do not represent the workers community

in the true sense, claims Dewan Muhammad Ali, President

of Bangladesh Rail Sramik Union and Vice President of

Bangladesh Trade Union Kendro (TUC). Union leaders,

who are supposed to be elected by worker-members of

the union through votes, are often chosen by the party

high ups of the political party they are associated

with. "If a leader is not elected by workers why

should he bother about the workers' welfare as long

as he is in the good

book of his mentors?" Ali explains.

General

workers, on their part, have gradually learnt not to

expect anything from trade unions. In many cases, especially

in the government-owned industries, the dominant feeling

about trade union is that of 'fear' more than anything

else. "In many places trade unions become the second

oppressor, considering that the first position is owned

by the owner/management. General workers there fear

the union leaders more than the Managing Director, because

if the MD does any injustice to them they can go to

the union, but if the union turns against him no one

can save him," Ali says.

Political-party-based

trade unionism that has been directly and indirectly

encouraged by both military and so-called democratic

governments has done the greatest harm to trade unionism,

believes Idris Ali, President of Bangladesh Garments

Workers Trade Union. A section of people who preach

this political-party-based trade unionism argue that

if a union leadership has direct relationship with the

government they are better able to work for the cause

of the workers. "No" comes the quick reply

from Idris. "Could the BNP-backed trade union stop

the closure of Adamjee Jute mill and save about 30 thousand

workers' job along with a few lakhs who were indirectly

dependent on the biggest jute mill of the region?"

Ali elaborates.

This

practice of handpicking union leaders instead of letting

them be elected by popular votes also serves the real

interest of the owners very well. "The owner or

management can then choose someone who they can easily

influence and exploit to their advantage," Ahsan

says.

There

is a very popular misconception about trade unions among

general people, who are accustomed to seeing it as an

obstacle to smooth functioning of an institution. "When

we talk to general workers about the importance of trade

union and try to organise them they often hesitate to

respond. They would often refer to it as a jhamela (trouble)

where they don't want to get into. They, of course,

cannot be blamed as what they have seen in the name

of trade union is really nothing but jhamela,"

Idris says. General workers need to be made conscious

about it, suggests Idris, but hastens to add that it

is an extremely difficult task. " As far as garments

workers are concerned, about 80% of them are illiterate

and aged between 16 to 25. The reason may be either

illiteracy or immaturity it is often hard to make them

aware of their rights and deprivation, and the fact

that the only solution to this is trade union,"

he says. Another problem with organising garments workers

is, Idris adds, they tend to change their workplace

frequently. "The convention has been to mobilise

workers taking the factory as the primary base, but,

we perhaps need to start approaching in terms of area,"

proposes Idris. There

is a very popular misconception about trade unions among

general people, who are accustomed to seeing it as an

obstacle to smooth functioning of an institution. "When

we talk to general workers about the importance of trade

union and try to organise them they often hesitate to

respond. They would often refer to it as a jhamela (trouble)

where they don't want to get into. They, of course,

cannot be blamed as what they have seen in the name

of trade union is really nothing but jhamela,"

Idris says. General workers need to be made conscious

about it, suggests Idris, but hastens to add that it

is an extremely difficult task. " As far as garments

workers are concerned, about 80% of them are illiterate

and aged between 16 to 25. The reason may be either

illiteracy or immaturity it is often hard to make them

aware of their rights and deprivation, and the fact

that the only solution to this is trade union,"

he says. Another problem with organising garments workers

is, Idris adds, they tend to change their workplace

frequently. "The convention has been to mobilise

workers taking the factory as the primary base, but,

we perhaps need to start approaching in terms of area,"

proposes Idris.

The

present bad state of the trade unions is not exactly

unexpected. It was, in a sense, inevitable. We live

in a society whose every fabric is polluted with corruption,

higher moral values are giving way to materialism, politicisation

is all pervasive. "How do you expect to see trade

unions clean when everything else is in bad shape?"

Manzurul poses his final question. It is a difficult

question, no doubt.

|

|

April

23, 2004. The Muktangan of Paltan still looks rain-drenched

from the heavy Baishakhi splash of the morning. At around

four in the afternoon, amidst the sporadic water puddles,

the people flock towards this place; representing different

labour organisations. Most have taken their seats. More

are joining the already present mass, which is slowly

growing in size. The hogla-mats that have been

spread out to cover the wet ground make up the turf

to sit on, the rest of the empty ground is gradually

being taken up by the joining mass who prefer to stand.

These are not the paid-for dummies that one sees in

those huge political rallies, these are labourers from

all sectors gathered to give voice to their own demands.

Their struggle is born out of the common predicament

of factory shut downs and job-losses, which they tackle

on their own terms.

April

23, 2004. The Muktangan of Paltan still looks rain-drenched

from the heavy Baishakhi splash of the morning. At around

four in the afternoon, amidst the sporadic water puddles,

the people flock towards this place; representing different

labour organisations. Most have taken their seats. More

are joining the already present mass, which is slowly

growing in size. The hogla-mats that have been

spread out to cover the wet ground make up the turf

to sit on, the rest of the empty ground is gradually

being taken up by the joining mass who prefer to stand.

These are not the paid-for dummies that one sees in

those huge political rallies, these are labourers from

all sectors gathered to give voice to their own demands.

Their struggle is born out of the common predicament

of factory shut downs and job-losses, which they tackle

on their own terms.  "The

number of mills in Bangladesh are diminishing at the

rate at which they are being denationalised," He

said. "There were 78 cotton mills, and now most

of them are closed. There are 18 government owned mills,

out of which 16 are still running. Although IMF, WTO

and many other international organisations are advocating

privatisation, in reality it is not working," Shahidullah

let the crowd know. His data depicts a bleak scenario

of the privatised spinning and cotton mills. Out of

54 privatised ones no one is running. Later in an interview

with SWM, he said, "78 mills were closed off, and

54 of them were denationalised and

"The

number of mills in Bangladesh are diminishing at the

rate at which they are being denationalised," He

said. "There were 78 cotton mills, and now most

of them are closed. There are 18 government owned mills,

out of which 16 are still running. Although IMF, WTO

and many other international organisations are advocating

privatisation, in reality it is not working," Shahidullah

let the crowd know. His data depicts a bleak scenario

of the privatised spinning and cotton mills. Out of

54 privatised ones no one is running. Later in an interview

with SWM, he said, "78 mills were closed off, and

54 of them were denationalised and  The

garment sector has an altogether different character.

Yet the lives of the workers in this precinct remain

as volatile as their brethren in others sectors. The

workers are job seekers from the poor hovels, who become

city-bound as resources in the rural areas are decimating

quickly. But, once in the cities, they become another

cog in the great wheel of an industry that so far has

based itself on minimum wage and the 'quota' rewarded

mostly by the USA.

The

garment sector has an altogether different character.

Yet the lives of the workers in this precinct remain

as volatile as their brethren in others sectors. The

workers are job seekers from the poor hovels, who become

city-bound as resources in the rural areas are decimating

quickly. But, once in the cities, they become another

cog in the great wheel of an industry that so far has

based itself on minimum wage and the 'quota' rewarded

mostly by the USA. As

cheap labour is the only source of income in this sector,

workers have never been given the status that they deserved.

In the last 18 or so years no proper union have been

allowed to operate to raise awareness about workers'

rights. Today in 3,300 factories situated mainly in

Dhaka, Chittagong, Narayanganj, Savar, Tongi and Gazipur,

a total of 1,320,000 women and 280,000 men are subjected

to the will of the owners. In absence of the law regarding

the national minimum wage, workers stand to lose. There

is this provision for fixing the minimum wage in every

sector, which is to be revised in every three years,

but in reality it has never been implemented, says a

report by the National Garment Workers Federation who

also furnished the present figures of factories and

workers. It also highlights that "in 1994, the

minimum wage for the unskilled labourers was fixed at

Tk. 930 per month, and for the skilled at Tk. 2,300,

but this was not implemented in all sectors".

As

cheap labour is the only source of income in this sector,

workers have never been given the status that they deserved.

In the last 18 or so years no proper union have been

allowed to operate to raise awareness about workers'

rights. Today in 3,300 factories situated mainly in

Dhaka, Chittagong, Narayanganj, Savar, Tongi and Gazipur,

a total of 1,320,000 women and 280,000 men are subjected

to the will of the owners. In absence of the law regarding

the national minimum wage, workers stand to lose. There

is this provision for fixing the minimum wage in every

sector, which is to be revised in every three years,

but in reality it has never been implemented, says a

report by the National Garment Workers Federation who

also furnished the present figures of factories and

workers. It also highlights that "in 1994, the

minimum wage for the unskilled labourers was fixed at

Tk. 930 per month, and for the skilled at Tk. 2,300,

but this was not implemented in all sectors".  Shahidullah

gives us the international scenario, "In the USA,

an hour's income is 13$, in Bangladesh, a garment worker

doesn't even make that in one month".

Shahidullah

gives us the international scenario, "In the USA,

an hour's income is 13$, in Bangladesh, a garment worker

doesn't even make that in one month".  It

was 83, Ershad's regime. A Trade Union, based in Fulbaria

bus stand was on strike. Suddenly talks of calling off

the strike were in circulation. Not because the government

had accepted their demands, but because of a deal between

the Union leader and the assigned government officials.

The bargain was that the government would release the

Union leader's brother who was facing a charge of bank

robbery, in exchange of withdrawal of the strike. The

story told by Manzurul Ahsan, President of the Communist

Party of Bangladesh, aptly illustrates the essential

characteristic of the current trade union culture of

the country.

It

was 83, Ershad's regime. A Trade Union, based in Fulbaria

bus stand was on strike. Suddenly talks of calling off

the strike were in circulation. Not because the government

had accepted their demands, but because of a deal between

the Union leader and the assigned government officials.

The bargain was that the government would release the

Union leader's brother who was facing a charge of bank

robbery, in exchange of withdrawal of the strike. The

story told by Manzurul Ahsan, President of the Communist

Party of Bangladesh, aptly illustrates the essential

characteristic of the current trade union culture of

the country. Besides,

in most cases, trade unions, particularly the ones associated

with BNP and AL, do not represent the workers community

in the true sense, claims Dewan Muhammad Ali, President

of Bangladesh Rail Sramik Union and Vice President of

Bangladesh Trade Union Kendro (TUC). Union leaders,

who are supposed to be elected by worker-members of

the union through votes, are often chosen by the party

high ups of the political party they are associated

with. "If a leader is not elected by workers why

should he bother about the workers' welfare as long

as he is in the good

book of his mentors?" Ali explains.

Besides,

in most cases, trade unions, particularly the ones associated

with BNP and AL, do not represent the workers community

in the true sense, claims Dewan Muhammad Ali, President

of Bangladesh Rail Sramik Union and Vice President of

Bangladesh Trade Union Kendro (TUC). Union leaders,

who are supposed to be elected by worker-members of

the union through votes, are often chosen by the party

high ups of the political party they are associated

with. "If a leader is not elected by workers why

should he bother about the workers' welfare as long

as he is in the good

book of his mentors?" Ali explains.  There

is a very popular misconception about trade unions among

general people, who are accustomed to seeing it as an

obstacle to smooth functioning of an institution. "When

we talk to general workers about the importance of trade

union and try to organise them they often hesitate to

respond. They would often refer to it as a jhamela (trouble)

where they don't want to get into. They, of course,

cannot be blamed as what they have seen in the name

of trade union is really nothing but jhamela,"

Idris says. General workers need to be made conscious

about it, suggests Idris, but hastens to add that it

is an extremely difficult task. " As far as garments

workers are concerned, about 80% of them are illiterate

and aged between 16 to 25. The reason may be either

illiteracy or immaturity it is often hard to make them

aware of their rights and deprivation, and the fact

that the only solution to this is trade union,"

he says. Another problem with organising garments workers

is, Idris adds, they tend to change their workplace

frequently. "The convention has been to mobilise

workers taking the factory as the primary base, but,

we perhaps need to start approaching in terms of area,"

proposes Idris.

There

is a very popular misconception about trade unions among

general people, who are accustomed to seeing it as an

obstacle to smooth functioning of an institution. "When

we talk to general workers about the importance of trade

union and try to organise them they often hesitate to

respond. They would often refer to it as a jhamela (trouble)

where they don't want to get into. They, of course,

cannot be blamed as what they have seen in the name

of trade union is really nothing but jhamela,"

Idris says. General workers need to be made conscious

about it, suggests Idris, but hastens to add that it

is an extremely difficult task. " As far as garments

workers are concerned, about 80% of them are illiterate

and aged between 16 to 25. The reason may be either

illiteracy or immaturity it is often hard to make them

aware of their rights and deprivation, and the fact

that the only solution to this is trade union,"

he says. Another problem with organising garments workers

is, Idris adds, they tend to change their workplace

frequently. "The convention has been to mobilise

workers taking the factory as the primary base, but,

we perhaps need to start approaching in terms of area,"

proposes Idris.