| |

Saving

Mostakina Saving

Mostakina

Shamim Ahsan

Kajalie Shehreen Islam

Down the long corridors

of Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH) at the One-Stop

Crisis Centre sits a little girl with a plastic doll

in her hand. In her orange and red floral printed dress

and two little ponytails at the top of her head, she

could be anyone's child. Except for the claw marks all

over her young cheeks, the nasty gash at the corner

of one eye, the severe burns down both her arms. Who

would tolerate such abuse silently in this day and age?

What kind of a person would inflict such torture on

anyone, let alone a child?

Mostakina is the ten-year-old domestic

"servant" girl everyone saw on the news last

week, with blood oozing out of the side of her face.

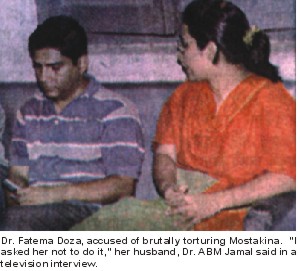

Rescued from the house of her employers, Dr. ABM Jamal

and Dr. Fatema Doza, Mostakina had been suffering such

cruelty for the past one year.

"I never told anyone," says

Mostakina, when asked whether she had gone to anyone

for help. "I was afraid she would beat me even

more."

As

any child would, Mostakina sometimes broke a few things

or thread would come out of a piece of clothing she

had washed. Considering the age of the girl, and the

fact that she did practically all the housework except

cooking -- from cleaning the floors to washing and ironing

clothes -- it really wasn't much. But Fatema Doza, a

doctor at DMCH, beat Mostakina for the most minor mistakes.

She would claw at her face and hit her with anything,

from sticks and brooms to bread rollers. The "Bua"

would also be hit and slapped and made to drink dirty

water when the dishes weren't washed clean enough. Mostakina

was made to drink Doza's children's urine. "She

would even spit on my rice," she says. As

any child would, Mostakina sometimes broke a few things

or thread would come out of a piece of clothing she

had washed. Considering the age of the girl, and the

fact that she did practically all the housework except

cooking -- from cleaning the floors to washing and ironing

clothes -- it really wasn't much. But Fatema Doza, a

doctor at DMCH, beat Mostakina for the most minor mistakes.

She would claw at her face and hit her with anything,

from sticks and brooms to bread rollers. The "Bua"

would also be hit and slapped and made to drink dirty

water when the dishes weren't washed clean enough. Mostakina

was made to drink Doza's children's urine. "She

would even spit on my rice," she says.

Mostakina

was not paid any monthly salary, usually on the pretext

of it being extracted against the price of the things

she had broken or ruined. She would also not be given

anything to eat the day she broke anything. Even when

she was, it was a bit of one piece of fish split many

ways.

Two

months ago, after Doza put a heated electric iron to

Mostakina's arm, the girl tried to run away. But before

she could get very far, the darwan caught her

and brought her back. Last week, when some thread came

out of another apparel, Doza hit Mostakina on the face

with a bread roller and burnt her other arm with the

iron. It was only when the injured girl went to put

out the garbage that a conscientious neighbour saw her

condition and called the police.

"I

want her to be punished," says the little girl.

"I don't want Phupa (Dr. ABM Jamal) to

be punished. He never hit me. He asked Phupi

not to hit me. But she wouldn't listen. She would beat

me when he was at the hospital. If he protested when

he got home, she would beat him too with a broom.”

"The

last time she did this," says Mostakina, "he

told her not to hit another person's child. If I died,

how would they face the consequences, who would pay

for the court case, he asked her. She said it would

be good if I really did die.”

Sub-Inspector

Baqui was loitering in Katabon intersection when he

received a call from the police headquarters at around

12.30 pm. He was instructed to go to an apartment building

at 2/10 Paribagh behind PG hospital where a minor girl

with serious injuries was to be found. In 15 minutes

Baqui was at the apartment building gate and the darwan

led him to the particular flat. But he couldn't enter

the house as it was locked. Upon instruction the girl

readily came to the verandah and talked to Baqui who

stood on the street. Baqui was confirmed about the incident.

He then decided to wait in the second floor in the landlord's

apartment as he was told that Dr. Jamal, who went to

bring his son back from school, would return soon. At

around 1.20 pm Jamal came back home and when asked about

the beating up of their housemaid, he simply denied

that any such incident had taken place. Baqui then told

that he had already talked to the girl and Jamal didn't

have any option but to allow him in. "I was shocked

when the girl was brought before me the scar with a

diametre of about one and a half inches, just a couple

of inches beneath her left eye was still fresh, with

a blackish shadow all around it", says Baqui. "There

were also burn injuries, perhaps one or two days old,

long and straight on both her forearms. When I asked

her she related how she was burnt with a heated iron,

her voice choking with suppressed tears. I found marks

of beating on almost all over her body; The woman seemed

to have beaten her with virtually everything she could

lay her hands on. I have never seen such inhuman torture

on such a small child in the six years of service,"

Baqui narrates.

Around

2.40pm the housewife returned home upon her husband's

phone call. "She first denied of ever putting the

iron on her face, and started to scold the girl right

before me asking her why she lied to me. Upon my insistence

she later conceded that she sometimes gave her 'mild

beatings', but that was due to Mostakina's intolerable

naughtiness or when she committed some 'grave sins'

like breaking a tea-cup or for not sweeping up the floors

as good as the woman wanted. Her husband also corroborated

her accusations saying that Mostakina was by nature

a little naughty but he admitted that it wasn't right

for his wife to treat her that way. He then tried to

condone his wife's behaviour saying that she sometimes

couldn't keep her cool and did these things in the heat

of the moment," Baqui. The couple was arrested

and brought to Ramna thana and Baqui lodged a case under

the Special Act for Prevention of Women and Children

Repression 2000, as the plaintiff. Around

2.40pm the housewife returned home upon her husband's

phone call. "She first denied of ever putting the

iron on her face, and started to scold the girl right

before me asking her why she lied to me. Upon my insistence

she later conceded that she sometimes gave her 'mild

beatings', but that was due to Mostakina's intolerable

naughtiness or when she committed some 'grave sins'

like breaking a tea-cup or for not sweeping up the floors

as good as the woman wanted. Her husband also corroborated

her accusations saying that Mostakina was by nature

a little naughty but he admitted that it wasn't right

for his wife to treat her that way. He then tried to

condone his wife's behaviour saying that she sometimes

couldn't keep her cool and did these things in the heat

of the moment," Baqui. The couple was arrested

and brought to Ramna thana and Baqui lodged a case under

the Special Act for Prevention of Women and Children

Repression 2000, as the plaintiff.

Mostakina is, in a sense, lucky. Unlike

many others who have been subjected to similar kind

of brutality and will continue to suffer indefinitely

Mostakina has at least been rescued from her tormentors.

But the big question now is will her tormentors be brought

to justice? If past records are any indication there

is almost no chance to see the perpetrators get punished.

In March of this year, Shirin, a 14-year-old

domestic worker in Rajshahi was raped and killed. Though

her employers said she committed suicide and hung herself,

police suspected they had something to do with the murder

and arrested them. Shirin's mother said she did not

want any trouble and that the money she could get was

all that mattered. But the next day, Shirin's employer

Sharmin Sultana Dipa, who often used to beat her, confessed

strangling Dipa to death and hanging her. It is still

not known who raped the teenager.

Hasna Hena worked for a woman in Mirpur.

Another maid at the house would do things wrong and

blame Hasna for it. When one day she put too many tea

leaves in a cup of tea Hasna had made for her mistress,

the woman tossed away the cup, beat Hasna and threw

her out of the house. Hasna's uncle later took her to

the police and the hospital. After two months at the

hospital, Hasna joined a shelter home, Proshanti.

Banu is another domestic worker who

joined the shelter home after spending a month in the

hospital after being beaten by her employer. The list

-- of only those who have actually filed cases -- goes

on.

Bangladesh National Women's Lawyers

Association, better known as BNWLA, a human rights organisation

that provides legal aid, is handling Mostakina's case

and has the experience of conducting more than two hundred

such cases of repression on domestic workers over the

last two decades. But it has succeeded in getting the

offender/s punished in only seven or eight cases. The

data provided by Mominul Islam Shuruz, Senior Investigation

Officer of BNWLA, lists various reasons for such a piteous

record.

A large number of cases fizzle out even

before they are taken up in the court while many more

end midway after good initial progress. Money does the

trick in most cases. The only thing an offender has

to do is get hold of the parents or guardians of the

victim and offer a few thousand taka, and everything

is settled. For a father who is forced to send his nine

or 10-year-old daughter away from home so that she can

earn her own food, money matters a lot. "10,000

taka for some bruises here and there appears too tempting

an offer to reject," says Shuruz. Besides, he adds,

for a poor, illiterate villager, police and court are

jhamela (trouble), and compromise in exchange of monetary

compensation seems a logical and even profitable option.

Shuruz then relates an incident involving a brutal killing

of a 14 year-old domestic help who was slaughtered by

a kitchen knife by the housewife. After one or two hearings

the victim's father stopped co-operating with us. We

kept watch on him and one day we found him having lunch

in the very house where his daughter worked and got

brutally killed. When I asked him why he gave up the

fight he seemed to have his answer ready: 'Shaheb has

given me 40 thousand taka. Besides, what is the use

of going to court? I am not going to get my daughter

back.'"

What many might find impossible to imagine

is that simple to some.

And

once there is a settlement between offenders and the

victim's family, the third party, that is BNWLA, which

is providing legal aid, has to simply wash its hands

of the case. "If we still persist, which we can

technically do, we might find ourselves in more trouble.

There have been cases where we were made to look as

if we had ulterior motive or some profit to make out

of the case in the guise of helping the victims,"

Shuruz explains. And

once there is a settlement between offenders and the

victim's family, the third party, that is BNWLA, which

is providing legal aid, has to simply wash its hands

of the case. "If we still persist, which we can

technically do, we might find ourselves in more trouble.

There have been cases where we were made to look as

if we had ulterior motive or some profit to make out

of the case in the guise of helping the victims,"

Shuruz explains.

Police, as everywhere, play their dirty

tricks here as well. Since they are directly involved

in all the different stages of a case, from submitting

the FIR (First Information Report) to submission of

the charge sheet and it is they who conduct the entire

investigation, they can influence the fate of a particular

case to a great extent. "Police often intentionally

leave big gaps while framing charges so that they can

allow criminals to get off the hook in exchange of money.

On the other hand the accused party -- in this case

the doctor couple -- has a lot to offer. And if money

fails to deliver they will wield their social, and if

need be, even political influence. That they will escape

punishment is almost a certainty," Shuruz cannot

help being pessimistic.

An interesting pattern can be detected

in the incidents of violence against domestic help.

Once the initial shock subsides, a conscious or unconscious

urge to paint the 'brutal offence' as a 'mistake' begins

to gain strength. The police who have rescued the victim,

the doctors who have treated the serious wounds, the

lawyer who is contesting on the victim's behalf and

finally even the judge who is deciding the case, start

to believe in the 'mistake theory' with growing conviction

each day. But why does it happen this way?

No doubt, poverty of the victim and

corruption of the law-enforcing agency are often responsible

for justice being denied, but there is another underlying

force, far stronger and more complex in nature, at play.

Abusing domestic help is not just another form of violence.

It ensues from a very acute sense of class-awareness

that is deeply buried in the collective consciousness

of the so-called half-educated, middle-class bhodrolok.

Once the vision gets blurred, he cannot see a person

as a human being, but tends to differentiate between

human beings using artificial criteria. Many of us,

members of the so-called middle class, are thus quite

biased and prejudicial in our judgement when considerating

something we consider below our status -- domestic workers

are easily relegated to lesser human beings who don't

deserve equal treatment.

Even after seeing the 10-year-old bearing

such ferocious, raw marks of brutality comments like

"you see, domestic workers are such a trouble",

"whatever you say maidservants are also no dervishes",

"sometimes, you just cannot bear with them",

"they are all ungrateful thieves" are common.

"I have even heard judges talking about how roguish

these domestic workers really are," says Shuruz.

No law, no honest police officer can solve it unless

we rectify our corrupt, partial perspective.

Mostakina's future is uncertain. Her

mother passed away before she can remember. She was

brought up by a neighbour. Her father later remarried

and someone from her village brought her to the doctor

couple. Her father hasn't visited her in the past year.

After her treatment is completed, she will go into BNWLA's

shelter home, Proshanti. Beyond that, as is the case

with many other girls there, no one really knows.

|

|

Saving

Mostakina

Saving

Mostakina As

any child would, Mostakina sometimes broke a few things

or thread would come out of a piece of clothing she

had washed. Considering the age of the girl, and the

fact that she did practically all the housework except

cooking -- from cleaning the floors to washing and ironing

clothes -- it really wasn't much. But Fatema Doza, a

doctor at DMCH, beat Mostakina for the most minor mistakes.

She would claw at her face and hit her with anything,

from sticks and brooms to bread rollers. The "Bua"

would also be hit and slapped and made to drink dirty

water when the dishes weren't washed clean enough. Mostakina

was made to drink Doza's children's urine. "She

would even spit on my rice," she says.

As

any child would, Mostakina sometimes broke a few things

or thread would come out of a piece of clothing she

had washed. Considering the age of the girl, and the

fact that she did practically all the housework except

cooking -- from cleaning the floors to washing and ironing

clothes -- it really wasn't much. But Fatema Doza, a

doctor at DMCH, beat Mostakina for the most minor mistakes.

She would claw at her face and hit her with anything,

from sticks and brooms to bread rollers. The "Bua"

would also be hit and slapped and made to drink dirty

water when the dishes weren't washed clean enough. Mostakina

was made to drink Doza's children's urine. "She

would even spit on my rice," she says. Around

2.40pm the housewife returned home upon her husband's

phone call. "She first denied of ever putting the

iron on her face, and started to scold the girl right

before me asking her why she lied to me. Upon my insistence

she later conceded that she sometimes gave her 'mild

beatings', but that was due to Mostakina's intolerable

naughtiness or when she committed some 'grave sins'

like breaking a tea-cup or for not sweeping up the floors

as good as the woman wanted. Her husband also corroborated

her accusations saying that Mostakina was by nature

a little naughty but he admitted that it wasn't right

for his wife to treat her that way. He then tried to

condone his wife's behaviour saying that she sometimes

couldn't keep her cool and did these things in the heat

of the moment," Baqui. The couple was arrested

and brought to Ramna thana and Baqui lodged a case under

the Special Act for Prevention of Women and Children

Repression 2000, as the plaintiff.

Around

2.40pm the housewife returned home upon her husband's

phone call. "She first denied of ever putting the

iron on her face, and started to scold the girl right

before me asking her why she lied to me. Upon my insistence

she later conceded that she sometimes gave her 'mild

beatings', but that was due to Mostakina's intolerable

naughtiness or when she committed some 'grave sins'

like breaking a tea-cup or for not sweeping up the floors

as good as the woman wanted. Her husband also corroborated

her accusations saying that Mostakina was by nature

a little naughty but he admitted that it wasn't right

for his wife to treat her that way. He then tried to

condone his wife's behaviour saying that she sometimes

couldn't keep her cool and did these things in the heat

of the moment," Baqui. The couple was arrested

and brought to Ramna thana and Baqui lodged a case under

the Special Act for Prevention of Women and Children

Repression 2000, as the plaintiff. And

once there is a settlement between offenders and the

victim's family, the third party, that is BNWLA, which

is providing legal aid, has to simply wash its hands

of the case. "If we still persist, which we can

technically do, we might find ourselves in more trouble.

There have been cases where we were made to look as

if we had ulterior motive or some profit to make out

of the case in the guise of helping the victims,"

Shuruz explains.

And

once there is a settlement between offenders and the

victim's family, the third party, that is BNWLA, which

is providing legal aid, has to simply wash its hands

of the case. "If we still persist, which we can

technically do, we might find ourselves in more trouble.

There have been cases where we were made to look as

if we had ulterior motive or some profit to make out

of the case in the guise of helping the victims,"

Shuruz explains.