|

Cover

Story

When

Dhaka Floundered When

Dhaka Floundered

Shamim

Ahsan

Only

a couple of weeks since Dhakaites recovered from a prolonged

flood, another rain-borne flood hit Dhaka on September 13.

The three-day long heavy shower caused serious waterlogging

in the city, yet again. For three days, life came to a virtual

standstill. People were forced into self-imprisonment, business

came to a halt, and acute crisis of drinking water made life

unbearable. Waterlogging, once thought to be a problem only

for a few low-lying areas in Dhaka, has suddenly threatened

to become a regular event in the rainy season. Could this

waterlogging have been avoided? What can we do to protect

Dhaka from getting waterlogged in the future?

Anwar

Hossain, a teacher at a private university, was surprised

as he stood at the main gate of his residence in Gopibagh

on the morning of September 13. The entire alley in front

of his house was under ankle-high water. It had been raining

since the previous day but he never thought it could drown

the road. There weren't any rickshaws in sight. He folded

the ends of his trousers, took his shoes in his hand and waded

through the waters. His surprise increased when he saw that

the main road was also drowned. It took him 15 minutes before

he could get hold of a rickshaw. The rickshaw puller demanded

Tk 20, three times higher than the usual fare, but he didn't

have any option. Anwar

Hossain, a teacher at a private university, was surprised

as he stood at the main gate of his residence in Gopibagh

on the morning of September 13. The entire alley in front

of his house was under ankle-high water. It had been raining

since the previous day but he never thought it could drown

the road. There weren't any rickshaws in sight. He folded

the ends of his trousers, took his shoes in his hand and waded

through the waters. His surprise increased when he saw that

the main road was also drowned. It took him 15 minutes before

he could get hold of a rickshaw. The rickshaw puller demanded

Tk 20, three times higher than the usual fare, but he didn't

have any option.

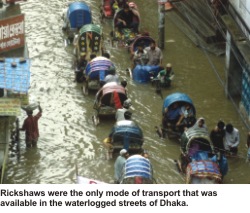

The heavy

downpour continued throughout the day and by the afternoon

most of the low lying areas in Dhaka were under water. Since

the day coincided with Shab-e-meraj, a general holiday for

the educational institutions, school-going children and their

parents were saved. But, thousands of people returning home

from their workplace found themselves stranded. There weren't

any buses or cabs or baby taxis -- all sorts of motor vehicles

had fled the streets, because, the engines could stop functioning

if they came into contact with water. The only modes of transport

that could be seen were rickshaws.

But

even the number of rickshaws was negligible. In Motijheel

commercial area hundreds of homebound people could be seen

standing in knee-deep water. Rickshaw-pullers, suddenly discovering

that the demand was many times higher than the supply, were

asking for inflated fares. Many chose to walk home, but women

and those who lived in far off places, were forced to comply

with the rickshaw-puller's demands. Farzana Karim, who works

at Mercantile Bank in Motijheel branch, had to pay Tk. 140

to go to Hatirpool from Motijheel. But

even the number of rickshaws was negligible. In Motijheel

commercial area hundreds of homebound people could be seen

standing in knee-deep water. Rickshaw-pullers, suddenly discovering

that the demand was many times higher than the supply, were

asking for inflated fares. Many chose to walk home, but women

and those who lived in far off places, were forced to comply

with the rickshaw-puller's demands. Farzana Karim, who works

at Mercantile Bank in Motijheel branch, had to pay Tk. 140

to go to Hatirpool from Motijheel.

Commuting

was not the only trouble though. When Anwar returned home

at around 7 pm, he could not believe his eyes. The rapidly

advancing water was only a few inches away from their reserve

tank. "Water didn't come this far even during the flood,"

he exclaims. He called a carpenter and quickly got a one-foot

wall installed surrounding the reserve tank.

Everybody

wasn't as alert as Anwar. Rainwater mixed with sewage water

coming out from the manholes intruded upon a large number

of reserve tanks in Old Dhaka. "We had to come all the

way from Gandaria to Motijheel to buy from WASA. My younger

brother and I hired a van, filled up two huge drums and brought

them home. It took us hours as our van had to advance avoiding

potholes and drains hiding under the cover of water,"

he says. Everybody

wasn't as alert as Anwar. Rainwater mixed with sewage water

coming out from the manholes intruded upon a large number

of reserve tanks in Old Dhaka. "We had to come all the

way from Gandaria to Motijheel to buy from WASA. My younger

brother and I hired a van, filled up two huge drums and brought

them home. It took us hours as our van had to advance avoiding

potholes and drains hiding under the cover of water,"

he says.

Many were

forced to move to their relatives' homes. "It didn't

help much though. My office is in Motijheel, so I had to come

all the way from Dhanmondi to Motijheel," says Shariful

Hasan, who, along with his family members had to move from

Hatkhola to Dhanmondi to stay with relatives. "We couldn't

sleep at night thinking our home, which we had left absolutely

empty, could be looted," Hasan adds.

There

were even more serious problems. Twenty-five water pumps for

raising water had gone under water causing major disruptions

in the water supply. Most of WASA's 45 pumps for clearing

out logged water from the city were found out of order when

they were needed the most. The strong wind accompanying heavy

rains tore apart many electricity lines disrupting power supply

in many areas. Many of the transformers had blownup. As water

crept into the electricity sub-station inside the Secretariat,

there wasn't any power for almost the entire day of September

13. An electricity tower of the Hasnabad-Kallyanpur 132 KV

transmission line at Keraniganj collapsed on the 13th resulting

in the power disruption in Mirpur, Kallyanpur, Kazipara, Shewrapara,

Agargaon, Jhikatola, Shyamoli and Adabor areas. There

were even more serious problems. Twenty-five water pumps for

raising water had gone under water causing major disruptions

in the water supply. Most of WASA's 45 pumps for clearing

out logged water from the city were found out of order when

they were needed the most. The strong wind accompanying heavy

rains tore apart many electricity lines disrupting power supply

in many areas. Many of the transformers had blownup. As water

crept into the electricity sub-station inside the Secretariat,

there wasn't any power for almost the entire day of September

13. An electricity tower of the Hasnabad-Kallyanpur 132 KV

transmission line at Keraniganj collapsed on the 13th resulting

in the power disruption in Mirpur, Kallyanpur, Kazipara, Shewrapara,

Agargaon, Jhikatola, Shyamoli and Adabor areas.

Commuters

who usually take the VIP road were in for a shock. Most of

it was completely flooded, including the part of the road

outside the PM's office. All the traffic had to be redirected

through Tejgaon, causing horrendous jams. Many roads of Gulshan

became inaccessible. Residents of Basundhara and Gulshan reported

having to deal with poisonous snakes creeping into the compounds

from the overflowing water-bodies.

Dhaka

is increasingly becoming a soft target of all sorts of natural

calamity. As the recent rain-borne flood literally paralysed

Dhaka for three days, the city dwellers sat helpless. Various

government agencies were of little help and preferred to wait

for Nature to show mercy on the city. But was there nothing

we could have done to prevent this latest disaster? Why does

a mega-city like Dhaka get waterlogged in the first place? Dhaka

is increasingly becoming a soft target of all sorts of natural

calamity. As the recent rain-borne flood literally paralysed

Dhaka for three days, the city dwellers sat helpless. Various

government agencies were of little help and preferred to wait

for Nature to show mercy on the city. But was there nothing

we could have done to prevent this latest disaster? Why does

a mega-city like Dhaka get waterlogged in the first place?

For

one thing, Dhaka simply doesn't have a proper drainage and

sewerage infrastructure. The city, moreover, is expanding

both horizontally and vertically at an uncontrollable pace,

along with its population. In comparison, the drainage and

sewerage facilities have grown little over the years. WASA

has 8 kilometres of box culvert, 225 kilometres of storm sewer

line (large round underground drains) and 1100 kilometres

of surface drain, which covers only 38 percent of the city

areas.

The

existing facilities cannot operate at full capacity because

of ill maintenance. DCC and WASA, both government bodies supposedly

responsible for protecting Dhaka from waterlogging, are busy

blaming each other for the crisis. According to DCC, the principal

responsibility of solving the waterlogging rests on WASA.

Clearing the surface drain is DCC's duty while WASA deals

with underground drains. Since WASA has not been clearing

the underground drains for a long time water through these

clogged drains cannot pass at its normal pace. Dhaka WASA

has shifted the blame on the record breaking rains in 50 years.

They however, stated that DCC was responsible for not clearing

the surface drains properly, which, WASA officials believes,

further worsened the situation. The feuding between the two

illustrates what is missing -- co-operation among the various

service providing agencies. The

existing facilities cannot operate at full capacity because

of ill maintenance. DCC and WASA, both government bodies supposedly

responsible for protecting Dhaka from waterlogging, are busy

blaming each other for the crisis. According to DCC, the principal

responsibility of solving the waterlogging rests on WASA.

Clearing the surface drain is DCC's duty while WASA deals

with underground drains. Since WASA has not been clearing

the underground drains for a long time water through these

clogged drains cannot pass at its normal pace. Dhaka WASA

has shifted the blame on the record breaking rains in 50 years.

They however, stated that DCC was responsible for not clearing

the surface drains properly, which, WASA officials believes,

further worsened the situation. The feuding between the two

illustrates what is missing -- co-operation among the various

service providing agencies.

While

DCC and WASA are guilty of negligence and inefficiency, a

lack of civic sense among a large section of city dwellers

also contributes to exacerbating the situation. All sorts

of solid wastes gathered from households, restaurants and

other establishments are often thrown into the drains blocking

the flow of wastewaters. Again those with houses just beside

the road often build shops in such a way that the drain gets

covered up.

The

primary culprit is the messy and inadequate drainage system.

A proper drainage system does not mean a few sewerage lines

and drains only; it means building up a network that interconnects

drains and sewerage lines with the natural water-bodies such

as ponds, lakes and canals. Unfortunately, Dhaka, which once

used to be dotted with some two dozen ponds, canals and lakes,

has been bereft of those water-bodies by the city's unplanned,

wholesale urbanisation in the last two decades. Numerous high

rise buildings have suddenly sprung up all over the city,

all sorts of natural water reservoirs both inside Dhaka and

on its suburbs have been quickly filled up by developers.

The lakes, once large and healthy, have shrunk and grown sickly

by indiscriminate encroachment of the land grabbers. The consequence

of such indiscriminate construction is right before our eyes.

A few hours of rain inundate many of the city streets and

during floods the entire low-lying areas of Dhaka go under

water for days on end. If water bodies had still been around

they could have easily contained the extra volume of water

that might have invaded the city because of floods or excessive

rains. The

primary culprit is the messy and inadequate drainage system.

A proper drainage system does not mean a few sewerage lines

and drains only; it means building up a network that interconnects

drains and sewerage lines with the natural water-bodies such

as ponds, lakes and canals. Unfortunately, Dhaka, which once

used to be dotted with some two dozen ponds, canals and lakes,

has been bereft of those water-bodies by the city's unplanned,

wholesale urbanisation in the last two decades. Numerous high

rise buildings have suddenly sprung up all over the city,

all sorts of natural water reservoirs both inside Dhaka and

on its suburbs have been quickly filled up by developers.

The lakes, once large and healthy, have shrunk and grown sickly

by indiscriminate encroachment of the land grabbers. The consequence

of such indiscriminate construction is right before our eyes.

A few hours of rain inundate many of the city streets and

during floods the entire low-lying areas of Dhaka go under

water for days on end. If water bodies had still been around

they could have easily contained the extra volume of water

that might have invaded the city because of floods or excessive

rains.

Selim

Bhuiyan, Chief Engineer, Flood Forecasting and Warning Centre,

lists some of the natural water reservoirs that have vanished

from Dhaka's map and the areas which have been suffering from

waterlogging as a consequence of that usurpation. The encroachment

on Katasur canal causes water logging in Rayerbazar and Mohammadpur

areas. Filling up Ramchandrapur canal is responsible for waterlogging

in Islambagh, Nawabgonj and Hazaribagh. A more than 30 metre

wide open canal in the southern part of Dhaka, Dholai Khal,

was filled up and a 2.5 metre by 2.5 metre box culvert was

installed in its place. Narrowing the canal has led to water-logging

in BUET, Bakhsibazar, Hosnidalan, Nimtali, Nazimuddin Road,

Bangshal, Aga Sadek Road, Gandaria, Postogola, and Faridabad

areas. Encroachment on Segunbagicha Khal at Maniknagar and

Manda causes waterlogging in Shantinagar, Inner Circular and

Middle Circular Roads, Arambagh, Fakirapul, Gulisthan Zero

Point, Motijheel, Dilkusha and Saidabad areas. Selim

Bhuiyan, Chief Engineer, Flood Forecasting and Warning Centre,

lists some of the natural water reservoirs that have vanished

from Dhaka's map and the areas which have been suffering from

waterlogging as a consequence of that usurpation. The encroachment

on Katasur canal causes water logging in Rayerbazar and Mohammadpur

areas. Filling up Ramchandrapur canal is responsible for waterlogging

in Islambagh, Nawabgonj and Hazaribagh. A more than 30 metre

wide open canal in the southern part of Dhaka, Dholai Khal,

was filled up and a 2.5 metre by 2.5 metre box culvert was

installed in its place. Narrowing the canal has led to water-logging

in BUET, Bakhsibazar, Hosnidalan, Nimtali, Nazimuddin Road,

Bangshal, Aga Sadek Road, Gandaria, Postogola, and Faridabad

areas. Encroachment on Segunbagicha Khal at Maniknagar and

Manda causes waterlogging in Shantinagar, Inner Circular and

Middle Circular Roads, Arambagh, Fakirapul, Gulisthan Zero

Point, Motijheel, Dilkusha and Saidabad areas.

Shrinking

of the Jirani Khal and choking up of the Shajahanpurt Khal

are responsible for waterlogging in Malibagh, Mouchak and

Shantibagh areas. Infringement on Shahjadpur Khal prevents

flushing out of rainwater and wastewater from Kuril, Pragati

Sarani and adjacent areas. Filling up a large portion of Begunbari

Khal has resulted in waterlogging in Tejgaon, Gulshan 1 and

Mohakhali areas. Encroachment on Mohakhali Khal is causing

water logging in Nakhalpara, Arjatpara, Rasulbagh and Shahinbagh.

The Kalyanpur pump regulating pond of the water supply agency

has been filled up, causing waterlogging in Taltala, Agargaon,

Kazipara, Shewrapara, Barabagh, Mirpur Section 1 and adjacent

areas. Encroachment on Ibrahimpur Khal and filling up of Diabari

Khal by the developers are responsible for creating water

logging in Uttara and Banani. Shrinking

of the Jirani Khal and choking up of the Shajahanpurt Khal

are responsible for waterlogging in Malibagh, Mouchak and

Shantibagh areas. Infringement on Shahjadpur Khal prevents

flushing out of rainwater and wastewater from Kuril, Pragati

Sarani and adjacent areas. Filling up a large portion of Begunbari

Khal has resulted in waterlogging in Tejgaon, Gulshan 1 and

Mohakhali areas. Encroachment on Mohakhali Khal is causing

water logging in Nakhalpara, Arjatpara, Rasulbagh and Shahinbagh.

The Kalyanpur pump regulating pond of the water supply agency

has been filled up, causing waterlogging in Taltala, Agargaon,

Kazipara, Shewrapara, Barabagh, Mirpur Section 1 and adjacent

areas. Encroachment on Ibrahimpur Khal and filling up of Diabari

Khal by the developers are responsible for creating water

logging in Uttara and Banani.

And

all this has been happening right under the nose of RAJUK

(Rajdhani Unnayan Katripakkha), the government agency entrusted

with the job of giving approval of any sort of buildings in

Dhaka. Now, why RAJUK has been approving the housing projects

by filling up wetlands is no mystery. "Sometimes developers

make two plans, one for getting the approval of RAJUK and

another one, which they originally implement," Bhuiyan

says. RAJUK, which is supposed to monitor if the approved

plan is being followed, is either neglecting their job, or

just keeping their eyes shut for reasons known to all. "Most

surprisingly, besides private developers, RAJUK itself is

filling up wetlands and the peripheral low lying areas,"

reveals ANH Akhtar Hossain, Managing Director, WASA. And

all this has been happening right under the nose of RAJUK

(Rajdhani Unnayan Katripakkha), the government agency entrusted

with the job of giving approval of any sort of buildings in

Dhaka. Now, why RAJUK has been approving the housing projects

by filling up wetlands is no mystery. "Sometimes developers

make two plans, one for getting the approval of RAJUK and

another one, which they originally implement," Bhuiyan

says. RAJUK, which is supposed to monitor if the approved

plan is being followed, is either neglecting their job, or

just keeping their eyes shut for reasons known to all. "Most

surprisingly, besides private developers, RAJUK itself is

filling up wetlands and the peripheral low lying areas,"

reveals ANH Akhtar Hossain, Managing Director, WASA.

Dhaka

has also grown into a concrete jungle, without very little

greenery. There is hardly any soil left in the city. So when

there is water either because of floods or heavy showers,

it cannot seep into the ground. Consequently, rain water or

floodwater takes longer to recede. This is also another reason

why the water level in Dhaka is going further down.

Bhuiyan

mentions another reason that makes the waterlogging situation

still worse. There is a tendency to raise the city streets

to save them from getting water logged. "What they don't

seem to understand is, if water cannot stay on the streets

it will then get into the houses more quickly than before,"

he explains. There has to be an outlet to clear away the water

and for that drains have to be made spacious and they have

to be kept clean, he points out.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2004

|

| |