|

Tradition

Preserving

a 200-year-old Family Tradition

Kavita

Charanji

Go

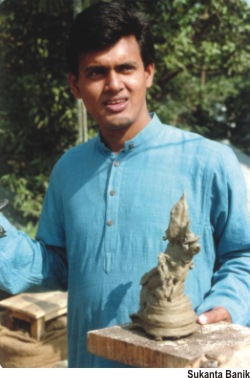

to Dhamrai village, located 39 kms northwest of Dhaka, and

you will glimpse an old mansion which dates back over 100

years. This is the picturesque home and workplace of Sukanta

Banik, proprietor of Dhamrai Metal Crafts. Carrying on a flourishing

200-year-old family business, Sukanata unveils an eight metal

statue which depicts a pantheon of Hindu gods and goddesses.

There is the central figure of Vishnu, the preserver, Lakshmi,

the goddess of wealth, Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge

and Garuda, the vehicle of Vishnu. Go

to Dhamrai village, located 39 kms northwest of Dhaka, and

you will glimpse an old mansion which dates back over 100

years. This is the picturesque home and workplace of Sukanta

Banik, proprietor of Dhamrai Metal Crafts. Carrying on a flourishing

200-year-old family business, Sukanata unveils an eight metal

statue which depicts a pantheon of Hindu gods and goddesses.

There is the central figure of Vishnu, the preserver, Lakshmi,

the goddess of wealth, Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge

and Garuda, the vehicle of Vishnu.

The eight metals are copper, tin, zinc, iron, mercury, lead,

gold and silver. Despite a hefty price tag of Taka 12,000,

'there is a huge potential market for statues in countries

such as India and the US,' says Banik. 'People in many parts

of the world believe that the metals represent the planets

and keep evil spirits away,' he adds.

Also

displayed in Banik's showroom are a variety of Buddhist, Jain

and Hindu statues, bowls, decorative items and pots made out

of metal.

Among

Banik's major current works is a traditional Indian chess

set which he began this June. The product, to be completed

by the end of November, is priced at Taka 1 lakh. Overall,

he says, the price tag for metal crafts varies from Taka 500

to Taka 60,000.

There

are five techniques in metal craft. Banik's firm most commonly

uses the Lost Wax Method for statues .

The

predominantly Hindu Dhamrai metal craft business dates way

back to the Pala dynasty (800-1100 AD). During this period

both early Buddhist and Hindu settlements once flourished.

Now Hindu, Buddhist, Jain and folk statues are a popular draw.

Banik's

family are pioneers in the metal craft. Beginning with his

great grandfather Sarat Chandra Banik and going downwards

to his grandfather Sarba Mohan Banik and his father Phani

Bhushan Banik, Sukanta took over the reins of the family business

in 2000. A post graduate in political science from Savar College,

Bhanik recalls those difficult early days: "When I joined,

the business was in a bad shape because of the slump in demand

from expatriate customers. This lasted from 1993-2000. Now

the business is run by my parents and me. The export market

is booming, especially US and India." Banik's

family are pioneers in the metal craft. Beginning with his

great grandfather Sarat Chandra Banik and going downwards

to his grandfather Sarba Mohan Banik and his father Phani

Bhushan Banik, Sukanta took over the reins of the family business

in 2000. A post graduate in political science from Savar College,

Bhanik recalls those difficult early days: "When I joined,

the business was in a bad shape because of the slump in demand

from expatriate customers. This lasted from 1993-2000. Now

the business is run by my parents and me. The export market

is booming, especially US and India."

A major supporter of Banik is the Matthew S Friedman, an USAID

official, who he describes as his 'friend, philosopher and

guide'. Freidman, who left Bangladesh last year, has authored

books on metal casting. He also helped Banik with slide shows

to show the techniques of this craft. This helped generate

awareness about the metal cast industry.

So

what is his company's unique selling proposition? "Other

countries have a master mold so that they can make more pieces

easily. In Bangladesh, we use the freehand technique and use

a one time use mold, so that there is a richer variety of

products. Also our statues are finer than that of others,

more ornate and better designed. We work with different metals

so there is a variation in statues, says Banik."

One

of Dhamrai Metal Crafts' major buyers is Kyle Tortora, a US

art dealer. The enterprising Kyle visits Dhamrai twice a year.

On one such visit, he bought a statue for Taka 9,000 and reaped

a bonanza when he sold it for US$ 1,500 in his own country.

Though

the export market is flourishing, Banik says it is still a

struggle for metal cast firms to eke out a living. Before

Liberation, for instance, people of about 33 villages in Dhamrai-Shimulia

were in the business, but now only around five families are

involved in the craft. Likewise with stiff competition from

cheaper aluminum and plastic products coming in from India

and other countries in the region, the market for these handcrafted

items has dwindled.

There

are other bottlenecks to deal with. It is quite a hassle for

example, to get the necessary export clearance from the Archaeology

Department which may declare that the crafts are not antique.

Then there is the problem of raw materials such as metal scrap

which are smuggled out from Bangladesh to India. There

are other bottlenecks to deal with. It is quite a hassle for

example, to get the necessary export clearance from the Archaeology

Department which may declare that the crafts are not antique.

Then there is the problem of raw materials such as metal scrap

which are smuggled out from Bangladesh to India.

Banik

has some strategies to counter these hurdles as chairperson

of the NGO called Initiative for the Preservation of Dhamrai

Metal Casting (IPDMC). This organisation trains artisans in

metal craft and the Lost Wax Method through workshops in Dhamrai,

Savar and other places.

'We

need more publicity and advertising about all the five techniques

of metal casting,' says Banik. What's heartening is the response

from school children to the craft. Last year, IPDMC held a

one-day workshop on the Lost Wax Method for 200 students from

American International School Dhaka, French International

School and Japanese International School. Recalls Banik, 'We

had a very good response. The children sat near the artisans

who explained the technique and then made butterflies, snakes,

elephants and so on. We cast these and gave them back to the

children. This year we have trained 160 students so far.'

A

major support to the IPDMC is the US $ 14,000 aid from the

US Ambassador's Fund. This will go to broaden the market through

documentaries, skill exchange programmes with Nepal, training

workshops in Dhamrai and school programmes.

For

those less adventurous, it is possible to see Banik's delicate

and eye catching metal work in Aarong and Aranya. His company

is also exploring marketing options with Probortana, a craft's

shop.

Lost

Wax Method

In

this technique, bees' wax is mixed with paraffin and

the wax is used to make statues. A 800 watt electricity

bulb is placed in the light box to help to keep the

wax soft and pliable. First the craftpersons make the

legs of the statue and then the other parts of the body.

Then the wax is heated and the parts are put together.

The product is then decorated. Subsequently, three layers

of clay are put on the metal piece. The first layer

is a very fine clay solution using a brush. The second

layer is clay mixed with jute fibre and sand. The third

layer is clay with rice husk.

The

next step is casting the mold. Around 100-120 kg of

metal is cast at a time. After the metalusually brass

in Bangladesh-- has been added to the crucible (a container

in which the raw unheated metal is placed) the mold

and the crucibles are placed in an oven for firing at

a high temperature. Subsequently, the melted metal is

poured into molds and given finishing touches.

|

Copyright (R)

thedailystar.net 2004

|