|

Cover

Story

A

Campus A

Campus

on Edge

Shamim

Ahsan and Kajalie Shehreen Islam

On

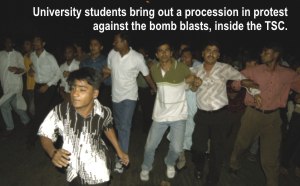

the evening of February 14, Dhaka University (DU) looked like

anything but a university campus. The previous day had been

a festive one, with Pahela Phalgun being celebrated by yellow-saree-clad

women, people coming to watch the film festival at the Teachers-Students

Centre (TSC) and hordes of others pouring into the nearby

Ekushey Boi Mela. That very day, the grounds had been filled

with happy young people meeting up and celebrating a day of

love, enjoying mock debates centring on the theme and just

hanging out with friends when, all of a sudden, the celebrations

turned into a chaotic tragedy.

Whether

it is to welcome the New Year or celebrate the national cricket

team's memorable victory, TSC has become the venue that pulls

the biggest crowds. No wonder that Valentine's Day or the

World Love Day programme attracted a few thousand youths to

TSC where a stage was raised in front of the Swoparjito Swadhinota

for a mock debate by the Dhaka University Debating Society

(DUDS).

"There

were lots of people," says Saiful, a fourth year student

of mass communication and journalism, "lots of outsiders

too, and everyone was just having fun."

At

around 7:25 pm, during the second part of the programme, a

parliamentary style debate on "recognising love as a

constitutional right" was in progress. Just as the opposition

leader had begun to speak, there was a loud sound. Most people

thought it was a tyre busting and just ignored it. The debate

resumed. At

around 7:25 pm, during the second part of the programme, a

parliamentary style debate on "recognising love as a

constitutional right" was in progress. Just as the opposition

leader had begun to speak, there was a loud sound. Most people

thought it was a tyre busting and just ignored it. The debate

resumed.

But when

the next three explosions happened right in their midst at

an interval of 20 to 30 seconds, people started to run, leaving

behind sandals and bags, taking refuge inside the TSC, nearby

residential halls and anywhere else they could hide. The fifth

blast took place 15 to 20 yards from the stage. Three unexploded

bombs were also later found in the area.

"When

the first bomb went off near the Central Library, we thought

they were fire-crackers," says Saiful. "It was only

when one exploded six or seven feet from me, in front of DUS

(Dhaka University Snacks), that I realised it was a bomb.

I fell trying to save a friend and we got trampled on. Everything

went dark."

Within

seconds, the panic-stricken crowds were running helter-skelter

in all directions, not realising where they would be safe.

Many fell on the street from the pushing and shoving, especially

women who were wearing saris. They screamed and begged for

help, but no one looked back. Within seconds, a long patch

of the street in front of the Swoparjito Swadhinota and the

beautiful island-like lawn before the DUS that were filled

to the brim with jubilant crowds became empty. The street

was littered with sandals and shoes, wallets, money, torn

pages of books and cards. Around 12 people were injured by

splinters while some 40 were hurt in the stampede that followed

the blasts. Within

seconds, the panic-stricken crowds were running helter-skelter

in all directions, not realising where they would be safe.

Many fell on the street from the pushing and shoving, especially

women who were wearing saris. They screamed and begged for

help, but no one looked back. Within seconds, a long patch

of the street in front of the Swoparjito Swadhinota and the

beautiful island-like lawn before the DUS that were filled

to the brim with jubilant crowds became empty. The street

was littered with sandals and shoes, wallets, money, torn

pages of books and cards. Around 12 people were injured by

splinters while some 40 were hurt in the stampede that followed

the blasts.

"I

thought I was going to die," says Mustafiz, a Master's

student of social welfare and vice-president of DUDS, who

was on stage when the explosions happened. "When I saw

that I was okay, I started looking for my friends." Three

or four of Mustafiz's club members were injured in the blasts.

Casualty-wise,

it wasn't as devastating as other recent incidents, but impact-wise

it was. The several thousand people who witnessed the attack

and those horrific moments after being bombarded from what

seemed like all around, are not likely to forget that evening

anytime soon. As they relate their experiences, it is obvious

that the trauma is still fresh.

Except

for two female students of DU and a young man who were under

treatment at Dhaka Medical College Hospital (DMCH), others

received mild injuries and were released later that evening

after receiving first aid.

A

day after the attack, 25-year-old Md. Shahin Mia lies wounded

in Ward 32, surrounded by relatives. There are quite a few

bloody spots from his left knee down to the ankle. The skin

on those spots is torn vertically. He has already undergone

a small operation in the morning (February 15) and has had

2 tin splinters removed from there. His relatives say he has

another splinter a little over his left ankle, which the doctors

thought would be better left alone for the time being. He

also shows the bandaged back part of his right thigh that

shows a splinter wound. A

day after the attack, 25-year-old Md. Shahin Mia lies wounded

in Ward 32, surrounded by relatives. There are quite a few

bloody spots from his left knee down to the ankle. The skin

on those spots is torn vertically. He has already undergone

a small operation in the morning (February 15) and has had

2 tin splinters removed from there. His relatives say he has

another splinter a little over his left ankle, which the doctors

thought would be better left alone for the time being. He

also shows the bandaged back part of his right thigh that

shows a splinter wound.

The attending

nurse assures that these are not serious injuries. Her consolation

is not lost on Shahin who appears enlivened by this revelation.

One of his relatives, Farid (not his real name), a DU student,

reveals that Shahin came to the campus to see him and stood

among the crowd enjoying the debate as he just came across

it on his way to SM hall where Farid resides.

Shahin

is apparently alright but seems a little disoriented when

answering questions. The attending doctor believes the trauma

he went through hasn't left him yet and might take years to

get over.

He remembers

the moment he received the injury. "I was standing about

a hundred feet away from the stage. Suddenly, I felt something

blast right beneath my feet, as if I had trampled on it somehow,

making a big sound," he says. Though he claims he didn't

lose consciousness, he doesn't remember what happened after

he was hit except that his eyes were burning and that after

a while he was carried by some unknown faces.

Fatematuzzohora

Tuhin, a second year student studying Arabic literature, and

Halima Akhter Deepa, a second year philosophy student, both

of whom have sustained injuries on the lower parts of their

legs, are in the same cabin, No 30, on the second floor, at

DMCH. They are friends and on that fateful evening they had

gone to the programme just a couple of minutes before the

bombs started exploding. Since Tuhin is a member of DUDS,

she and her friend found a place on one corner of the stage. Fatematuzzohora

Tuhin, a second year student studying Arabic literature, and

Halima Akhter Deepa, a second year philosophy student, both

of whom have sustained injuries on the lower parts of their

legs, are in the same cabin, No 30, on the second floor, at

DMCH. They are friends and on that fateful evening they had

gone to the programme just a couple of minutes before the

bombs started exploding. Since Tuhin is a member of DUDS,

she and her friend found a place on one corner of the stage.

"We

had just taken our seats and asked one of the volunteers who

was standing near us what the topic was and after he had said

only one or two words I was deafened by a huge sound,"

Tuhin says.

Her

friend, Deepa, who was sitting right beside her says, "For

a second I didn't know what was going on and what I should

do. At first I could not see anything as there was thick smoke

all around. The moment I regained my senses I jumped down

from the stage and started to run in the direction of Rokeya

Hall. As I was running there were at least three more blasts

and all of them seemed to have happened right beside me. When

I reached near the hall gate, a man stopped me and showed

me that my shalwar had caught on fire," she

says.

Their

injuries are not serious either and they will recover soon,

but they probably won't ever forget the hellish moments they

experienced that evening. "I have never been so scared

before. As I was trying to work out in which direction I should

run in the smoke, it seemed to me I was dying," relates

Tuhin.

Needless

to say, for most people, the incident was shocking. Most students

spent the next day calling home to inform their families that

they were alright.

"I

just don't go to public gatherings of any sort anymore,"

says a shocked Farhan, a student of the university.

Interestingly,

Farhan says that when he was passing through the place of

the disaster later that night, there was no electricity in

the area and people were cleaning up the scene of the crime.

The next morning, there was no trace of the tragedy, and,

some say, no evidence either. Interestingly,

Farhan says that when he was passing through the place of

the disaster later that night, there was no electricity in

the area and people were cleaning up the scene of the crime.

The next morning, there was no trace of the tragedy, and,

some say, no evidence either.

An explosives

expert related to Shumon, a fourth year DU student, who reached

the scene 10 or 15 minutes after it happened, that the bombs

were Improvised Explosive Device. If put on the ground, they

would be set off by any sort of vibration. In his opinion,

such explosives would not kill or severely injure anyone but

give out a lot of smoke and noise, to, basically, disperse

crowds.

"I

have a feeling this was just an experiment," says Shumon,

"to see how people react. Perhaps something that might

be applied later."

Shumon

does not seem visibly traumatised by the incident. It has

just become too common, he says. But, like most people, he

is obviously frustrated.

"I

was sitting outside the Boi Mela the day after the incident,"

he says, "having tea at a stall. The tea-seller was saying

that sales had been low that day because hardly anyone came

to the mela. A bearded man, around 40, said he wished

that three or four people had been killed in the Valentine's

Day blasts."

What

surprised most people was that, despite extra security on

campus that day with the hartal and the book fair

going on, something like this could have happened. The police

and Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) proved ineffective in preventing

the attack. Though everyone going to the Boi Mela had to go

through a metal detector, people attending the Valentine's

Day celebrations didn't go through any sort of security check,

as has become routine for most celebrations after the Ramna

Botomul blasts in 2001.

Most students

don't seem to think that the attacks were carried out by any

large organisation, but, perhaps a small group that just does

not like the concept of Valentine's Day.

"They

may not even be religious extremists," says Farhan, "rather,

some random people who want to take advantage of their reputation."

Farhan does not believe that the attacks were in any way related

to the August 21 carnage or the Habiganj blasts that killed

AL leader SAMS Kibria. "It might even have been one of

the student organisations," he adds.

Whoever

the culprit, as always, the general students of Dhaka University

are the ones to suffer. Two days of strike have already been

enforced by the Anti-Communalism and Anti-Terrorism Alliance,

consisting of the student front of the Awami League, Bangladesh

Chhatra League (BCL), BCL Jasad, Chhatra Dhara (student front

of Bikalpo Dhara Bangladesh), Chhatra Samity, Chhatra Oikkyo

and Chhatra Moitree, with threats of an impending indefinite

strike if one of the arrested BCL leaders is not released.

Tension rules at the university residential halls where the

different student organisations are at daggers with each other,

with hardly any atmosphere for co-existence. Whoever

the culprit, as always, the general students of Dhaka University

are the ones to suffer. Two days of strike have already been

enforced by the Anti-Communalism and Anti-Terrorism Alliance,

consisting of the student front of the Awami League, Bangladesh

Chhatra League (BCL), BCL Jasad, Chhatra Dhara (student front

of Bikalpo Dhara Bangladesh), Chhatra Samity, Chhatra Oikkyo

and Chhatra Moitree, with threats of an impending indefinite

strike if one of the arrested BCL leaders is not released.

Tension rules at the university residential halls where the

different student organisations are at daggers with each other,

with hardly any atmosphere for co-existence.

The usual

investigating committee has been formed, headed by Pro-Vice-Chancellor

Prof Yusuf Haider, but has not yet made any headway. In the

meantime, students remain scared, anxious and on edge -- as

does the whole country, it seems -- almost as if waiting for

the next attack.

Seven

days into the TSC bomb blast, the police are yet to make any

breakthrough. SI Naser, the Investigation Officer says the

probe is on, but refuses to say if they have made any progress.

In the

meantime, three madrassa students were arrested from the Ekushey

programme at Jahangirnagar University (JU). They were found

with a timer and an audio tape of a speech by an unknown religious

cleric defending Osama bin Laden, Mufti Amini and Shaikhul

Hadith.

As

the TSC bomb blast occurred after a series of bomb blasts

and grenade attacks over the last few years, there is a general

tendency to link them. After some 20 such incidents since

1999, the terror of bomb attacks never seemed so real before.

We are living with the fear of the next attack; we just don't

know when and where it will happen. The fact that the much

hyped RAB was in charge of security along with the regular

forces shows how insecure we are. Many have vowed to avoid

any type of gathering, but that is not a realistic solution.

The obvious remedy is to catch the perpetrators and bring

them to justice. Everybody knows this but nothing is happening

to that end.

Living

in a Living

in a

Tinderbox

Ahmede

Hussain

While

all the major political parties remain indifferent, ordinary

citizens have been trying to come to terms with the bomb blasts

that have created a sense of panic in this dangerously divided

society.

Twenty-four-year old Moumita Chowdhury was

talking to her fiance at a Pahela Baishakh gathering when

a bomb went off in Ramna Green in 2001. Panic gripped her

and she ran for cover as a string of blasts soon followed.

Shrapnel hit her left thigh when a bomb exploded in an abandoned

package a few paces away.

Moumita, then a student of economics, was

taken to a private clinic where her left leg was amputated.

Four years after that traumatic incident she is still trying

to grapple with life. Her fiance left her immediately after

the surgery; and Moumita, a budding Rabindra Sangeet artiste

at that time, quit singing. "I know my life will not

be the same again," she says.

Like several other blasts that have ripped

through the country in the last 10 years, police investigation

into the blasts has failed to make any significant headway.

The

subsequent governments' failure to bring the culprits to book

has given birth to widespread rumours. Of them, a long-running

conspiracy theory, primarily aimed at the ruling BNP-led coalition

government, blames Islamic extremists for the attacks. In

its full five-year term, the Bangladesh Awami League (AL)

could not nab the culprits behind the blasts, but this did

not deter the party from speculating about the identity of

the culprits. Fearing an electoral defeat to the BNP, the

AL fed several rumours before the 2001 general elections that

pointed the finger at BNP's electoral allies Jamaat and Islamic

Oikkya Jote. The

subsequent governments' failure to bring the culprits to book

has given birth to widespread rumours. Of them, a long-running

conspiracy theory, primarily aimed at the ruling BNP-led coalition

government, blames Islamic extremists for the attacks. In

its full five-year term, the Bangladesh Awami League (AL)

could not nab the culprits behind the blasts, but this did

not deter the party from speculating about the identity of

the culprits. Fearing an electoral defeat to the BNP, the

AL fed several rumours before the 2001 general elections that

pointed the finger at BNP's electoral allies Jamaat and Islamic

Oikkya Jote.

The AL, however, failed to get the cutting

edge over its archrival in the general elections. The BNP,

with the help of its Islamic allies, came back to power riding

an electoral landslide; and blasts, meanwhile, have continued

to rock the country at a regular interval.

Another conspiracy theory has taken birth

at the ruling Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) headquarters.

To repel a barrage of local and international criticism that

accused the party for being lenient with the religious fundamentalists,

the BNP shifted the blame on the AL. Immediately after coming

to power in 2001, the party blamed the AL for planting bombs

in public places to portray the country as a haven for Islamic

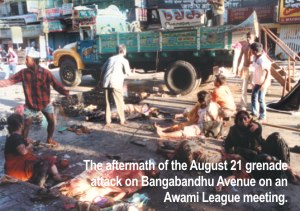

extremists. This disturbing trend repeated itself when grenades

were thrown at Sheikh Hasina, the leader of the opposition,

at a rally in Dhaka on August 21 last year.

In fact, in the aftermath of the killing of

the former finance minister SAMS Kibria, in a characteristic

display of arrogance, the BNP has blamed the AL for taking

the injured leader to Dhaka on a microbus, instead of waiting

in Habiganj for the government-sent helicopter to come. The

party has never publicly apologised, though local newspapers

have found that it was the government that took an unusually

long time to make any decision about sending a helicopter

for the injured AL-leader. In fact, investigation shows that

the government never really informed the AL or Kibria's family

about the availability of the helicopter, if such a decision

was taken at all.

Though 22 AL-workers, including party leader

Ivy Rahman, died in the August 21 blasts, questions were raised

by some BNP members as to how Hasina survived the mayhem when

so many people had died.

Bomb

attacks, meanwhile, have continued; on February 16, eight

people were critically injured in two identical bomb attacks

on two BRAC offices in Naogaon and a branch of the Grameen

Bank in Sirajganj. Three grenades were later recovered from

another BRAC office. Bomb

attacks, meanwhile, have continued; on February 16, eight

people were critically injured in two identical bomb attacks

on two BRAC offices in Naogaon and a branch of the Grameen

Bank in Sirajganj. Three grenades were later recovered from

another BRAC office.

Public opinion about the blasts has remained

dangerously divided in a country where politics dominate people's

lives. In the absence of any proper investigation, rumour

has remained people's only source of information.

Brig Shahedul Anam Khan, a security analyst,

thinks both the major political parties' indifference is helping

the culprits to get away with the crime.

"The AL has never been serious in its

claim; if they had really believed what they say now, they

would have been able to arrest some zealots while they were

in power. The BNP, on the other hand, has been amazingly soft

on the extremists. Otherwise, how would you explain the fact

that when the whole world believes in the presence of religious

extremists in the country, why would the BNP try to hush this

thing up?" Anam asks.

In fact, as the history of these blasts go,

both the parties' ambivalent political stance has been the

prime hindrance to a proper investigation.

"The government, it seems, does not want

to run an independent investigation as they fear it will open

a whole new Pandora's box.

"How can one expect the police to nab

the culprits when the prime minister herself thinks the AL

is behind the killing?" Anam asks.

The

government has remained conspicuously silent when the so-called

Jagrata Muslim Janata Bangladesh (Awakened Ordinary Muslims

of Bangladesh; JMJB) has been killing ordinary citizens in

the name of Islam. Though the PM has ordered a crackdown on

the militant outfit, the police have failed to arrest Bangla

Bhai, the so-called operations commander of the JMJB. The

government has remained conspicuously silent when the so-called

Jagrata Muslim Janata Bangladesh (Awakened Ordinary Muslims

of Bangladesh; JMJB) has been killing ordinary citizens in

the name of Islam. Though the PM has ordered a crackdown on

the militant outfit, the police have failed to arrest Bangla

Bhai, the so-called operations commander of the JMJB.

Lately the police have made some arrests,

and of them, Shafiqullah, a member of the JMJB, has confessed

the party's link to some blasts that took place across the

country.

"The JMJB is determined to carry on attacks

on all forms of anti-Islamic activity until an Islamic revolution

takes place in the country," he says in a statement given

to a First Class Magistrate. He admitted that JMJB had been

responsible for a number of bomb attacks on NGOs.

Farman Ali, another JMJB member who was arrested

in Natore, told the police that JMJB operatives regularly

held meetings at the Baitul Mukarram Mosque and Kakrail Mosque

in Dhaka to chalk out their plans.

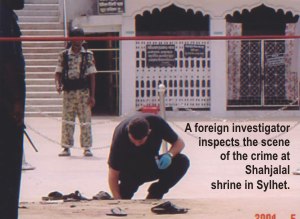

In

fact, alarm bells were raised on September 19, 2003, when

police arrested Maulana Abdur Rauf, leader of Jamiatul Mujaheedin

Bangladesh (JMB), along with his 17 accomplices. Though Rauf

confessed to going to Afghanistan to fight for the Talibans,

the militant leader was later granted bail. The police, too,

have lost tab on him, and recent arrests made by the police

suggest that Rauf is back to where he belongs-- different

madrassas across the country to train aspiring militants. In

fact, alarm bells were raised on September 19, 2003, when

police arrested Maulana Abdur Rauf, leader of Jamiatul Mujaheedin

Bangladesh (JMB), along with his 17 accomplices. Though Rauf

confessed to going to Afghanistan to fight for the Talibans,

the militant leader was later granted bail. The police, too,

have lost tab on him, and recent arrests made by the police

suggest that Rauf is back to where he belongs-- different

madrassas across the country to train aspiring militants.

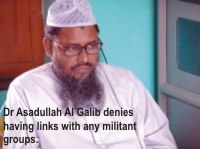

The recent arrests also make a surprising

revelation. "Dr Asadullah Al Galib, a teacher at the

Arabic department of Rajshahi University, is involved with

the JMJB and is leading it towards an Islamic revolution,"

Shafiqullah told the police. Farman Ali, too, says that Dr

Galib is the regional commander (South) of the group.

"I was introduced to Galib and Shahi

Bhai (Abdur Rahman, leader of JMB), at a religious programme

in a graveyard in Narayanganj and we discussed ways to bomb

anti-Islamic programmes in the country," Farman says.

The

story took a dramatic turn on February 17 when a docket containing

Shafiqullah's confessional statement went missing from the

court in Bogra. Sources said a top staff of the Bogra police

took the docket to the office of the Superintendent of Police

(SP), though the SP does not have any authority to read any

confessional statement. Police, however, told journalists

that they know nothing about its whereabouts. The

story took a dramatic turn on February 17 when a docket containing

Shafiqullah's confessional statement went missing from the

court in Bogra. Sources said a top staff of the Bogra police

took the docket to the office of the Superintendent of Police

(SP), though the SP does not have any authority to read any

confessional statement. Police, however, told journalists

that they know nothing about its whereabouts.

Though both Shafiqullah and Farman's confessions

implicate Dr Asadullah Al Galib as a terrorist, the professor

remains a free man. "Of course we have political ambitions

for an Islamic state, but we don't follow traditional politics.

We have our Islamic way of invitation and Jihad, which is

devoid of terrorism. We will continue our movement unto death,"

Dr Galib tells journalists.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005

|