|

Cover

Story Cover

Story

Hygiene

Gone

Haywire

Kajalie Shehreen Islam

Tanima, a student of Dhaka University, has just finished her early morning classes. She has a whole day of classes ahead of her. She thinks about whether she can get through them all right. She has tried to her best calculations to drink only a limited amount of water at a certain time before leaving the house. But it's a hot summer day, and she can't help but take apprehensive sips from her water bottle every little while. By mid-day, Tanima has no choice but to give in.

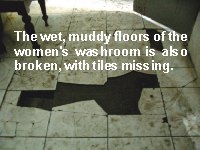

Very reluctantly, she walks to the women's common room. As usual, it's filled with female students chatting, eating, studying . . . and lining up to use the washroom. When her turn comes, Tanima braces herself. Leaving her dupatta on a dust-covered chair outside one of the four toilets, she enters, holding her breath. Tiptoeing around the broken tiles and trying to get as little of her sandals as possible dirty on the wet, muddy floors, she has to start breathing again at some point. But the sickening stench, which has never failed to disappoint her, makes her want to throw up for the umpteenth time.

She has to get out of here, she thinks. Taking one look at the flush handle, she remembers the day, in her first year, when she was new and naïve enough to pull it, despite the warnings of a friend. "How can you not flush a toilet?" she had thought, dangerously innocent. Just as she had pulled it, a long pipe in front of her had erupted with disgustingly brown water and flooded the washroom, and a part of the common room. She has to get out of here, she thinks. Taking one look at the flush handle, she remembers the day, in her first year, when she was new and naïve enough to pull it, despite the warnings of a friend. "How can you not flush a toilet?" she had thought, dangerously innocent. Just as she had pulled it, a long pipe in front of her had erupted with disgustingly brown water and flooded the washroom, and a part of the common room.

Knowing better today, Tanima hurries out after washing her hands, grateful to be using the washroom with the tap that actually works and the door that actually locks. She runs out of the common room and into the open air to be able to breathe freely again. "It's over!" she congratulates herself, forcing herself not to mentally add, "Only until tomorrow . . ."

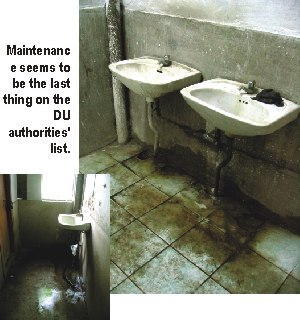

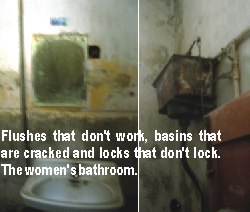

No one expects to find spic and span washrooms with automatic flushes at Dhaka University (DU) -- or anywhere else in the country, for that matter. But what they do expect is basic hygiene. For that, however, some basic amenities are necessary. But in the washrooms of the country's most prestigious educational institution, a maintenance employee himself admits that the taps of one of the washrooms in the women's common room don't work. The door of another is broken, and the lock of yet another one does not work. In one of the toilets, mud comes out from the ground. There is no system of flushing whatsoever, because, though each latrine has a flush, none of them work.

While the washrooms of the Science, Commerce and other faculties and most of the residential halls -- especially the women's dormitories and the newer halls -- are in somewhat tolerable condition, the greatest load falls on the toilets of the Kala Bhaban (Arts Faculty).

"An eight-storey plan for the Kala Bhaban was originally made for a population of 5,000," says Proctor AKA Firoz Ahmed. "Today, the four stories that have been built so far house some 15,000 students belonging to not only the Arts but also the Social Science faculty, along with various other scattered institutes, centres and office rooms." There aren't even enough classrooms or teachers' offices, notes the proctor. "An eight-storey plan for the Kala Bhaban was originally made for a population of 5,000," says Proctor AKA Firoz Ahmed. "Today, the four stories that have been built so far house some 15,000 students belonging to not only the Arts but also the Social Science faculty, along with various other scattered institutes, centres and office rooms." There aren't even enough classrooms or teachers' offices, notes the proctor.

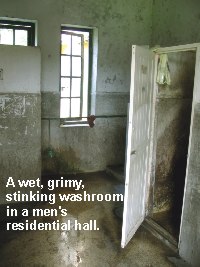

There are four men's toilets on each of the four floors of the Kala Bhaban -- which can be smelled from afar. While people can hold their breath when walking by the latter, there are classes and even teachers' office rooms near many of them, and it becomes torture to take classes or sit in those rooms.

And while there is already a shortage of washrooms compared to the number of students using them, teachers of some departments actually keep the washrooms near them locked, reserved for their sole use, thus increasing the pressure on the accessible ones.

The women, on the other hand, have only the six toilets -- four of them functional -- in the two common rooms on the ground and third floors of the building.

Sumona, a Masters student of DU says, "Women, no matter which floor they're on, have to run to the ground or third floors to use the washroom."

Not everyone is lucky to even find a bathroom when they need one, however. Parveen, a former student of International Relations at DU, remembers running to the toilet before an exam but not being able to make it through the long line without being late and thus having to give a very uncomfortable exam. Not everyone is lucky to even find a bathroom when they need one, however. Parveen, a former student of International Relations at DU, remembers running to the toilet before an exam but not being able to make it through the long line without being late and thus having to give a very uncomfortable exam.

Finding a washroom to go to, however, is not quite the blessing one would hope for either.

"I wish someone would blindfold me every time I have to use the university toilets," says Sumona.

One woman janitor is responsible for cleaning all the washrooms in both the common rooms on the ground and third floors of the building twice daily. Within 10 minutes of her having cleaned them, about five students use each of the toilets again. By the time the next cleaning is due, the situation of the toilets is akin to that of the sparse public toilets we see in some places in the city, if not worse. For the women who have to use them in between, it's little short of a nightmare.

"I can't even sit and eat in the common room because of the smell coming from the toilets," says Alpona, a fourth year student.

Most students agree that they use the toilets only in cases of absolute emergency and only because they have classes all day.

"It's worse than a pigsty!" exclaims third year student Masum. "Even if you wear four masks you won't be able to block out the smell!"

Saleha points out the half-broken door of one of the women's toilets, making it completely useless. "They also have signs asking students to throw their trash into the garbage cans, but there are none," she says. Saleha points out the half-broken door of one of the women's toilets, making it completely useless. "They also have signs asking students to throw their trash into the garbage cans, but there are none," she says.

Munni, a third year student of Dhaka University, slipped and fell on the wet, slippery floor of her residential hall, hurting her face. Mimi, another student, complains that there are no lights in many of the washrooms, making the ordeal even harder.

"The students are also at fault to an extent," adds Mimi. "They don't keep the washrooms as clean as they could either, like throwing tissue paper on the floors."

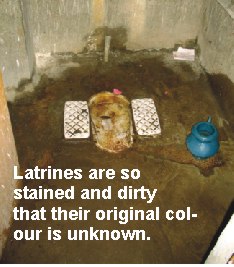

"No respectable person can use the university toilets," says fourth year student Farhad. "Taps are broken, bodnas are cracked. You can't even tell what the original colour of the latrines once was; they're so dirty and stained." He adds that it is common to find bottles of Phensidyl in the washrooms, along with people smoking pot and heroine.

"It's impossible to use the university toilets," says Rezaul Hassan, a DU employee. "Taps don't work, pipes are cracked, and they're dirty beyond imagination." "It's impossible to use the university toilets," says Rezaul Hassan, a DU employee. "Taps don't work, pipes are cracked, and they're dirty beyond imagination."

"They seem to use only water and no cleaning materials like bleaching powder to wash the toilets," says Ratna, a second year student.

The same complaint is made by residential students who claim that bleaching powder and real cleaning material is used only once a week. Some halls have cleaners come in three times a week.

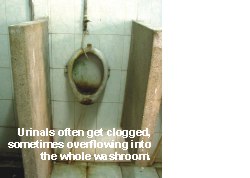

Others are supposed to be cleaned twice a day. Urinals in the men's washrooms often become clogged to the point of overflowing, sometimes flooding the whole washroom.

"I've seen a bottle of Phensidyl lying around in one of the men's toilets at the Kala Bhaban for over a month now," says an employee of the institution. "You would think it would have been removed during cleaning -- if the washrooms were ever cleaned."

Sadeq, a resident of Jagannath Hall who claims he has to cover his face with a <>gamchha every time he goes to the hall washroom says, "Once when I went to the bathroom, there was water dripping on me from the bathroom on the floor above. Sometimes," he adds, "the pipes get clogged and flood the washrooms."

Sometimes there is no water in the washrooms, complain students. At other times, the broken taps keep dripping water, sometimes to the point of overflowing. A student points out that this is a big waste, ultimately leading to water shortages in other areas in the city.

Many students actually try their best not to go to the washrooms at DU, or at least, to go as less as possible. This applies not only to university toilets but to washrooms around the country, and to women even more so. Not relieving the bladder for long hours can lead to urinary tract infection (UTI) and kidney disease. Many women students suffer from these problems for the simplest reason: because they cannot use the washroom.

Bazlur Rahman, Section Officer at the Dean's Office of DU, says that the DU washrooms are much better today than they were 20 years ago. They even have tiles, he says. "A couple of them, which take the most load, are a little bad," he admits, "but generally, they're alright." Apparently, even many outsiders who come to visit the campus in the evenings use the toilets on the outer side of the building which remain open. Bazlur Rahman, Section Officer at the Dean's Office of DU, says that the DU washrooms are much better today than they were 20 years ago. They even have tiles, he says. "A couple of them, which take the most load, are a little bad," he admits, "but generally, they're alright." Apparently, even many outsiders who come to visit the campus in the evenings use the toilets on the outer side of the building which remain open.

Rahman, however, does confess that they are understaffed. Thirteen janitors clean around 20 toilets at the Kala Bhaban twice a day.

"Classes start at 8," he adds, "and there is hardly any time to clean the toilets."

The budget allotted for maintenance is also less than half what is actually needed, he says. "Say we need 10 bottles of phenyl," he explains, "but our budget allows only two."

"We also had a plan to install flushes," he says, "but it hasn't worked out as yet." Rahman admits that there is still some scope for repairs and improvement, but that he thinks the washrooms are reasonably clean.

DU Proctor Prof Firoz Ahmed estimates that the toilets of the women's common rooms -- originally designed for the use of about 180 female students -- are used by at least 1,800 female students every day.

"No matter how clean we try and keep the toilets," he says, "logistically, it won't work because of the enormous load of students on the building." "No matter how clean we try and keep the toilets," he says, "logistically, it won't work because of the enormous load of students on the building."

The only way it can be managed, he says, is to separate the various faculties currently housed in the Kala Bhaban. "The Commerce faculty has recently shifted to a new building," says Prof Firoz, "which has reduced the pressure somewhat. Things would become more manageable if the Social Science faculty was also moved to another building, so that the Kala Bhaban would only have to take the load it was originally intended for."

However, says Assistant Proctor Siddiqur Rahman Khan, a committee has recently been formed to look into recommendations made for repairing the Kala Bhaban. A budget has also been proposed which includes fixing the washrooms and replacing the tile floors with mosaic.

TheWomen's Common Rooms

The biggest problem with maintenance -- as with everything else at DU -- seems to be that no one quite knows what they're responsible for. A handful of DU officials had to spend a few minutes informing each other and deciding who's responsible for what regarding the washrooms at DU and maintenance of the women's common rooms. Those who do know their duties, don't do it.

All the women's common rooms have are a few tables and chairs, with nothing in the form of entertainment. While a budget has been proposed for adding new or better things like more fans, floor mats, new basins in the washrooms and games, implementation still seems like a far cry. Despite repeated requests for repairs and proper maintenance to the relevant authorities, nothing is ever done. All the women's common rooms have are a few tables and chairs, with nothing in the form of entertainment. While a budget has been proposed for adding new or better things like more fans, floor mats, new basins in the washrooms and games, implementation still seems like a far cry. Despite repeated requests for repairs and proper maintenance to the relevant authorities, nothing is ever done.

In fact, two men (as opposed to the single woman janitor) employed to dust the furniture in the two common rooms, instead of doing anything of the like, have set up a snack shop inside one of them. One of them apparently also started a photocopy corner in which he soon got his (male) relative a job. Inside common rooms that are apparently strictly for women, three or four men run small canteens of sorts, and another two or three a photocopy corner. In fact, two men (as opposed to the single woman janitor) employed to dust the furniture in the two common rooms, instead of doing anything of the like, have set up a snack shop inside one of them. One of them apparently also started a photocopy corner in which he soon got his (male) relative a job. Inside common rooms that are apparently strictly for women, three or four men run small canteens of sorts, and another two or three a photocopy corner.

"We can't even sit around freely in the common room because of the men," complains a student.

While one university employee brushes this off by saying there is no alternative because, "Women won't be able to manage the photocopiers as well and as fast as men," the Proctor, Prof AKA Firoz Ahmed, says he will look into the matter and employ women in the common rooms if necessary and feasible.

Senior Assistant Proctor Fatema Begum points out that the proctor's office is not actually in charge of the women's common rooms. "They are the responsibility of the Dhaka University Central Students' Union's (DUCSU) secretary, and because DUCSU is currently defunct, the proctor's office has volunteered to manage the common rooms," she says.

|

Plans for expansion estimated to cost Tk. 2 crore have also been approved by the university authorities, says Md. Amir Hossain, Chief Engineer of DU. They are only waiting for a green signal from the government, for the scheme is a part of an umbrella project of the latter. Vertical expansion of the Kala Bhaban will add two more floors, which will include men's washrooms as per the existing foundation. A simultaneous plan for shifting the Social Science faculty into a new building will greatly reduce the load of students on the Arts Faculty.

The vertical expansion scheme does not, however, include any plans for additional common rooms for women. "The proposal has to come from the university authorities," says Hossain, and only then can the engineering section (literally) build on it.

"The number of common rooms for women should definitely be increased," stresses Hossain. "Men can and do use toilets anywhere. Women have the hardest time. I think it should be given top priority."

Section Officer Bazlur Rahman, on the other hand, asked about why the expansion plans do not include any more women's common rooms, says, "Perhaps no one thought of it. But if they are needed, they will be included."

Compared to the shortage in even classrooms in the Kala Bhaban, the visibly peeled and broken down walls and furniture, the limited hall seats and the numerous other problems of the institution, the DU authorities may not consider the problem of the shortage of washrooms or their poor maintenance to be a major crisis. But the fact remains that the issue is one of basic health and hygiene that have serious, long-term consequences in the lives of the thousands of students the institution is responsible for.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |

| |