|

Cover

Story

Murtaja Baseer

The Flamboyant Realist

Murtaja Baseer was one of the artists who diverged from the traditional way of picture making in the 1960s. By banding with other artists of his generation who were exposed to Euro-American modernism, he too ventured into a newer ground and started doing abstraction. Yet he is not merely known as an abstractionist in this region. Being an artist who is willing to transgress his past experiences, he has tackled different idioms at different times. There were phases that mark his journey from one way of picture making to another. His oeuvre is proof that he has a tendency to express himself in varied languages of art. But underneath all the variations there lurks an artist who is unrelenting in his effort to seek beauty in every day reality. With his tendency to focus on the beauty of things, he can be bracketed in the category of the naturalist, with his willingness to find a unity in forms, he can be called a formalist, but no matter how he has been able to express himself, he is, at the core, an incorrigible realist. On his 73rd birthday of his life he is the subject of a major retrospective. SWM looks into the life and art of this septuagenarian on the eve of his show that started on August 17, at the Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts. Murtaja Baseer was one of the artists who diverged from the traditional way of picture making in the 1960s. By banding with other artists of his generation who were exposed to Euro-American modernism, he too ventured into a newer ground and started doing abstraction. Yet he is not merely known as an abstractionist in this region. Being an artist who is willing to transgress his past experiences, he has tackled different idioms at different times. There were phases that mark his journey from one way of picture making to another. His oeuvre is proof that he has a tendency to express himself in varied languages of art. But underneath all the variations there lurks an artist who is unrelenting in his effort to seek beauty in every day reality. With his tendency to focus on the beauty of things, he can be bracketed in the category of the naturalist, with his willingness to find a unity in forms, he can be called a formalist, but no matter how he has been able to express himself, he is, at the core, an incorrigible realist. On his 73rd birthday of his life he is the subject of a major retrospective. SWM looks into the life and art of this septuagenarian on the eve of his show that started on August 17, at the Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts.

|

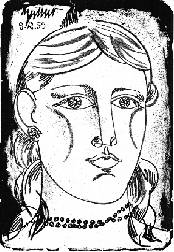

Girl with Necklace , Lithograph , 1959 . |

"I thought I was going to do a show entirely of my drawings, but then I thought better of it and now I am having a retrospective covering the whole spectrum of my life's works," Murtaja Baseer, the flamboyant artist says about his 17th solo. In a room of his apartment at Indira Road, he is surrounded by books, painted and unpainted canvases as well as the files that contain valuable records of his artistic journey that began in 1949. This was the year he was enrolled in the Government Institute of Arts, the present Institute of Fine Arts. In his room he shows his usual agility in seeking out any relevant data, as most things have little chance of being misplaced. "I am meticulous about keeping things in order," he says with a hint of pride in his voice. His room looks more like a scholar's den than an artist's studio. In fact in the late eighties he plunged into the world of research. Starting with a British Council fellowship on the heritage of Bengal he later studied the terracotta art on brick temple in West Bengal with a scholarship under the Indian Council for Cultural Relations. That was in the 1980s, before he gave up painting to pursue studies in numismatic. "I gave up painting for seven years for studying the heritage of Bengal in numismatic. I started researching from 1990, and the book came out in 1997, it was titled: 'The Social Reality of Bengal in the Coins and Tablets of the Habsi Sultans,'" Baseer sheds light on what many would call an aberration. But the artist is proud to have delved into areas other than art. He proudly proclaims that outside Bengal, in the rest of India, he is known for his works in numismatic with articles written by him in the Journal of the Numismatic Society of India, a reputed journal of the Varanasi University.

|

| Zainul Abedin , Pencil , 1953 . |

At present, on a rainy day he is as usual in an ecstatic mode, displaying his characteristic exuberance while rummaging through bits and pieces of notes and paper-clips that is related to his life and art. Dwelling on the subject of his latest artistic venture he speaks of a realistic portrait that he has done after a long time. He walks up to the rack of his canvases and whisks out a portraiture and announces that it was the first realistic rendition of anyone since his student days. "The last realistic picture I painted was way back in 1954, and that too was the work that I did during the last exam at the Government Institute of Arts.

Baseer considers the work realistic as its oil gestures refer back to the skin of the real subject, still the face seems to skirt round the usual play of light and shade, a ploy that renders a painting experimental. Dodging the representation of volume, which gives the illusion of the real, he attained a kind of simplicity that most of his recent figurative exploits thrive on. The new portrait gives sign of the flesh, whereas his works are deliberately flat, as flat as a monotonously painted canvas.

|

Girl in Front of Mirror, 1959, the oil on jute canvas that he did after coming back from Florence. |

As he inspects the work it opens up a floodgate of memories, it instigates the turning back of the clock. "Back in 1950, when I was in second year at college, one day, Anwarul Haq, my teacher, asked me to change my place in the classroom so that Abdur Razzak, who always stood first, could get a better view of the still-life arranged to be done in watercolour. It made me so sad that I went out of the classroom and started crying standing on the veranda," Baseer remembers. He could not handle watercolour, as he found it to be too messy a medium. Fortunately, Shafiuddin Ahmed, who was known for his strictness with his students saw Baseer crying, and he asked him to visit his home. "I was surprised that I was invited to the house of a teacher who was known as the one who would usually greet his students at the door and would never invite anyone inside, his hand would uninvitingly be held to the side of the door," Baseer recalls. But Shafiuddin not only invited the novice to his home, he showed him his oil works. " He was known for his prints; for the first time in my life I discovered that he was a painter too," recalls Baseer. Shafiuddin Ahmed showed him a way out of his predicament by asking him to start using the oil medium. "He showed me how to prepare the cardboard that was used in shoe boxes with gum to paint on them," he says.

|

| Sacrifice , the oil on ply wood done in 1954 when he was still a student. |

There was another event that started him in the direction of the artist he was later to become. "In June of 1950, right after the first year final exam was over, I was arrested for putting up posters of the then banned communist party, of which I was a member. I was granted bail after six months, and as I went back to the institute I found out that we were in for a series of watercolour classes. I could not manage to handle the medium properly," Baseer remembers. He went straight to Zainul Abedin and told him that making art was beyond his means. But Zainul, as prescient as he was, did not relent, he asked for Aminul Islam, then a second year student of the Institute. He asked Baseer whether he knew Aminul or not. Baseer had to resort to lying. "Aminul was the secret member of the then banned Communist Party's student wing Chhatra Federation, and I was a recruit of the same organisation, so I said I did not know him," Murtaja explains.

Zainul introduced Aminul to Baseer as a second year student who was well known for his works in oil, asking the first to guide the latter in his artistic endeavour. From that point on, Aminul became a mentor to Baseer and they went outdoors together to capture the scenic beauty of the outskirts of Dhaka. "He became a 'second teacher' to me who introduced me to oil painting," Baseer says acknowledging the debt to the older painter. He learnt oil at an early stage, only when he was in second year and it relieved him from the pain of worrying over the watercolour medium that he never learned to use to his advantage. Baseer pinned his hopes on oil, and it is its "gloss" that still attracts him.

|

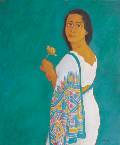

Woman with Yellow Rose, oil on canvas, 2003. One of the works belonging to the batch of figurative paintings that he embarked on in the late 1990s.. |

Baseer completed his course in 1954. "It was not a degree, nor even a certificate course back then, I just completed my course, and to this day I include it in my bio-data as a completion of a course in fine arts," he points out.

Right after he wrapped up his studies, he started to venture outdoors with fellow artists Qayyum Chowdhury, Abdur Razzak and Rashid Chowdhury. "We used to go in groups for studies outdoors; Dhanmondi and Rampura were part of the villages back then. Dhaka comprised mostly of the old part of the city, and the Dhaka Stadium, which was being built, was the last outpost of the city," he recalls.

However, what swayed the young mind is not the scenic beauty of the city's periphery. Baseer's young mind had never been alighted by the arts of Nandalal Bose or Abanidranath Tagore or any other traditionalists. He was attracted to the young bunch of Indian painters who either came back from or were still living in Paris. "In the Statement paper that was being published from Kolkata, there was a series of articles on artists like Laxman Pye, Akbar Padamsee, Ram Kumar and Paritosh Sen, they all used to light up my imagination," he relates.

|

| Epitaph for the Martyrs , oil on canvas, 1977. |

From these artists he had his pick. It was Sen whose works influenced him the most. "Paritosh Sen's works made me think, made me wonder. What I used to imagine I could find its trace in his work, his works provide a lot of stimulation," he elucidates. He was young and impressionable, and Sen had already made waves in the Indian art scene with his technique of creating contour drawings with a palette knife. "I took my cue from him and started using the palette knife to build up the contours of human figures in my works," he concedes.

By the year 1954, his involvement with the Communist Party had already waned. The case for plastering the poster of the Communist Party continued for one and a half years. "I was acquitted on the ground that there was no eye witness," Baseer recalls. "I gave up politics but my commitment to the common people still informs my thinking and my art," he claims.

The commitment that still sways Baseer goes back a long way; his entry into the world of art is also tied to his involvement with the Communist Party. "Back in 1947, when I was a student of class nine I was asked to produce portraits of Marx, Lenin and Stalin for the party office. We were living in Bogra, and Bhabani Sen, a renowned communist leader, came to Bogra and saw my feat," remembers Baseer. The boy of class nine asked for an autograph of the leader, and Sen, who had already come to know of the fact that Baseer was the artist of the portraits of the Russian communist leaders, wrote in his autograph, "The task of the artist is to express the essence of life and travails of the masses in such a way so that it reinvigorates the society." Baseer still treasures the autograph that Sen gave, and to this day while showing it to others, he is filled with inspiration and verve. The commitment that still sways Baseer goes back a long way; his entry into the world of art is also tied to his involvement with the Communist Party. "Back in 1947, when I was a student of class nine I was asked to produce portraits of Marx, Lenin and Stalin for the party office. We were living in Bogra, and Bhabani Sen, a renowned communist leader, came to Bogra and saw my feat," remembers Baseer. The boy of class nine asked for an autograph of the leader, and Sen, who had already come to know of the fact that Baseer was the artist of the portraits of the Russian communist leaders, wrote in his autograph, "The task of the artist is to express the essence of life and travails of the masses in such a way so that it reinvigorates the society." Baseer still treasures the autograph that Sen gave, and to this day while showing it to others, he is filled with inspiration and verve.

"I believe in commitment to the people, my political background has always been a source of my pride," Baseer points out. The same man is also committed to the paint and brush. "I never even dreamt of becoming an artist when I was a child. I was an active member of the Communist Party, and the party wanted me to get admission into Art College to organise the students," he adds. His famous father, Dr. Shahidullah, envisaged a different course of studies for his seventh son in the family of nine children. "He wanted me to complete my Bachelors degree first. When I announced my firm commitment to get enrolled in the Government Institute of Arts, he asked me to study in Viswa Bharati, Santiniketan, but stick to insistance because I was politically motivated," recalls Baseer.

Right after completing his course in art from Dhaka in 1954, he went to Kolkata to get his Teachers' Training Certificate, an art appreciation course. "Without completing this course one could not enter the profession of teaching in West Bengal. At first they did not allow me to take admission; when they found out that I was the son of Dr Muhammad Shahidullah, they gave in," Murtaja recounts.

|

| The Kalima Tayeba - 13 , oil on canvas , 2002 . |

Murtaja completed the course, and during this time he went to visit Ramkinkar Baize in Shantiniketan. "Baize was then working on his famous sculpture of the Santal family. He took me to his home and showed me his paintings, I was hugely moved by their colours and expression, they were a mixture of expressionism and impressionism," he recalls. He remembers his idea about modern art, he said, "Modern art is like a violin played at intervals in a symphony, it announces itself from time to time but mostly blends in with the rest of the harmony."

When Baseer went to Shantiniketan the enmity between the two giants -- Nandalal Bose and Ramkinkar Baize was already a well-known fact.

"Baize even asked me not tell Bose that I visited him first," remembers Baseer. He later visited the Master painter Bose and got an invitation to get admission in Kala Bhabana, Viswa Bharati. "But I was not interested in the schooling of Shantiniketan. I was attracted to the works of Paritosh Sen, and I had the chance to meet him as well as Atul Basu and Jamini Roy in Kolkata," he continues.

His meeting with Sen was an event that had an artistic consequence. "He showed me how to use the palette knife by hand, he taught me to make the lines sharp. You would see the difference in my paintings after the meeting," Baseer attests, pointing out the difference in palettes in a book published by the Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy as part of a series on pioneers of Modern art in Bangladesh. "The minimisation of colour and the simplification of forms" are the two principles that he learned from Sen. And his correspondence to Sen in the year between 1954 and 1955 proves that he and the older artist had built a rapport that went beyond the confines of the canvas.

Meanwhile in the domain of art, Baseer had made some advances; he painted Ila Mitra, the legendary left-wing leader, lying in a hospital bed, an expectant mother, husking maiden and many other pictures that expressed a newly acquired boldness. "The expectant mother became all the rage, as no one could envisage a young artist tackling such a subject," he remembers. Back then Fazle Lohani wrote a piece on Murtaja Baseer, and "it was the first piece on any artist published in this region."

|

Face , oil and lacquer on masonite , 1962 . |

In 1956, it was time to explore some alien terrain. Baseer went to study in Italy. However, it did not cause him to rethink his artistic goals. "Even in Italy I had drawn my inspiration from people, I remained faithful to the ideals that developed in me during my early years," emphasises the artist whose first headway in Italy was through a visual ploy that he called "transparency". "It suddenly occurred to me that I could get rid of the idea of background by making it a part of the figures in front of it, I started to make the figures transparent showing the background through them," he says.

Studies in Academia di Belli-arti, Florence, Italy, had one deciding influence on him. Baseer became attracted to classical art. The Etruscan wall paintings and the Greek Amphora paintings were the twin source that the artist had resorted to. "There are people who used to tell me that I drew my inspiration from Picasso, but I used to tell them that our sources were the same," he explains.

|

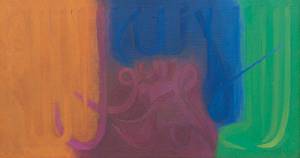

| The wing - 68 , Oil on canvas , 2005 . |

For an artist who loves "human drama" and paints only to express his allegiance to populist ideals, how did Baseer digress into abstraction? "I would not call myself an abstract artist, I would love to be bracketed in the realist category, as my sources had always been the reality around me," he declares. About his wall series, his first unpeopled canvases, he says, stem from real experiences. He wrote in an article published in Vision in 1963, "I was watching some white fungus on the ceiling, scrutinising the forms and shapes. Suddenly I saw a huge, abnormal face peeping out of it, which seemed to be crying silently. And that gave me my first break from my (old) style."

Another event in 1958 also made him rethink his style of painting. He went to Paris and saw a show of Madiglini. "The show was full of similar looking paintings, they made me think that I would not want to produce an oeuvre that would look the same," says Baseer.

His change was gradual. From 1960 to 1961 he produced 40 paintings with faces and bird motifs. With these the transformation was already underway. By then he was also craving for a change in his own life. "I wanted to have new experiences, a new mode of life," he now recalls. In May of 1962 he got married, and the following two months were barren as far as artistic activity was concerned. "At first I found it difficult to get used to the systematic way of life. I started painting after two months and structural unity was still my aim, yet the textural formation and the colours like golden and silver overwhelmed the drawing," Baseer recalls. He did 30 paintings at a stretch. And about their content he has his own theory. "The paintings are like my autobiography, I did not paint them for the sake of it. I consider myself a medium that absorbs human conditions and situations and try to portray personalised reactions," he adds.

|

| Village scene , oil on masonite,1962 |

However politically inclined Baseer was in his early life, his paintings dealt more and more with pure pictorial concerns than real life. But his claim to his own culture and people did sparkle from time to time. Even in words he was bold and forthright during the tumultuous Ayub era. In an article published in Vision he wrote an answer to that awkward question of his time, which concerned the subject of Pakistani culture. He wrote, "Let me answer you by a counter question, does Pakistani culture exist, with two wings of the country separated by more than a thousand miles, with profound differences in language, customs, and everything and only religion being the common bond?"

In his paintings he kept on doting on the formal possibilities while expressing the interior reality. He turned to abstraction. "Everybody was doing that; I felt I was lagging behind, so I started a series that stemmed from walls

that I named 'Wall'," he recalls. But he also adds that the realist in him never died. "Even with non-objective paintings my elements refer back to reality," he adds.

His homage to the martyrs of 1971 too was expressed in an idiom that hovers between realism and abstraction. He left for Paris early in 1971. As he did not participate in the freedom struggle a sense of guilt welled up in his heart. Soon he reconciled that overwhelming sense with the urge to express things that would link him to the war of independence. His famous 'epitaph' series was the result of this reconciliation.

"It was by fluke that it came to my mind that I could draw the pebbles to express my homage to the people who sacrificed their lives in the war of '71," Baseer relates. He started to paint the series in 1972 and continued till 1976. "Some of them were painted in Paris and the rest has been done in Chittagong and Dhaka when I came back from Paris in 1974," he adds. Before embarking on them he did a number of drawings that expressed the struggle of the Bangalis in metaphors. Those drawings, where people were seen confronting a beast, were the yield of the year 1971. With his 'epitaph' series he mounted a show at the Shilpakala Academy in 1976.

Subir Chowdhury, the director of the Bengal gallery of Fine Arts, is the man who curated that show. He has always been fascinated by the works of Baseer. "There are some series that I did not like, as a whole I find him interesting. I feel a special affinity to him, so, we finally sat and planned an exhibition, I suggested that it better be the one that covers the entire spectrum of his life. Few of the paintings of the well-known 'wall' series has been brought in from Pakistan to be included in this show," says Chowdhury. However, the most revered works of the artist, which is the 'epitaph' series, is represented by only one painting that artist could manage to borrow from a collector.

On 17 August Murtaja Baseer turned 73, and it is no coincidence that his retrospective would kick off on that day. The Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts, with the help of the artist planned this show to coincide with his birthday.

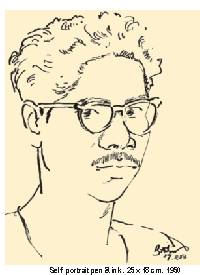

Three days before the show, Baseer is busy scrutinising his oeuvre in the confine of the Bengal gallery. Most of the paintings are already up on the wall, while bunch of smallish works is still lying on the floor in front of an empty wall. "These are not for sale, these are to be kept. My daughters insisted that they remain with the family," says Baseer. The works in question are his self-portraits. Most are pen drawings, there is one unfinished oil that dates back to his student days in Florence. These represent the artist at different stages in his life, and Baseer is an artist who had always looked at his life in terms of stages. In the gallery too, the paintings refer to various stages that he went through. There are a couple of paintings that he did on Kalema Tyeba, there is a series on wings of butterflies, the wall, and the epitaph series is also there, and lastly there are a number of paintings that represent his return to figuration in the late 1990s.

Baseer was a teacher for the best part of his life. He joined the Department of Fine Arts of Chittagong University as an assistant professor in 1973, and finally retired from teaching in 1998. But as he takes a tour through his 17th solo, he shows no sign of wear and tear. His mental as well as physical vigour is unfazed by the years that he has left behind.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |

| |