| Cover

Story

|

Fragments in Space, by Rahman, one of the new generation abstract artists |

Art in our time

Mustafa Zaman

"The days of the art movement are behind us," says noted artist Murtaja Baseer. However, the art scene in Bangladesh is often referred to as a thriving one. Although Baseer feels that art pursued as the goal of a group of artists has seen its demise, art as the expression of the individual has blossomed in the last twenty or so years. If the pre-independent era is marked by creative actions on the part of the pioneers who banded together to make a mark at the national level, the post--independent period is defined by the thrust towards the expansion of the horizon through various art practices.

Today, in the absence of group activities, where young and old have combined their might, newer idioms are being practised through individual effort. Not that the idea of artists working in groups has vanished all together; it is the spirit of pursuing a single school of thought that has taken a beating. While in the sixties the young and the aspirant modernists like Mohammad Kibria, Aminul Islam, Murtaja Baseer, Kazi Abdul Baset and many of their contemporaries set out to pursue the 'Abstract Language' borrowed from the West, today the younger generation artists choose to avoid such homogeneous goals. They want variations, they want newness. But, how far have they progressed in their endeavour to claim a niche of their own in the creative domain? How do they fair in the context of the rapidly changing art scene of the world? After 34 years of independence where do the artists of Bangladesh stand?

What Murtaja Baseer refers to as the art movement of their time, first made its public appearance in January 21, 1951. That was the inaugural day of the first of the two consecutive annual art exhibitions by the Dhaka Art Group, a group comprising the major artists of the country as well as the students of the Government Institute of Arts (GIA), which is now known as the Institute of Fine Arts (IFA). The show was held at the then Litton Hall, part of the Shahidullah Hall at present. "Its patron was the Prime Minister Nurul Amin himself, and the president of the Dhaka Art Group was Zainul Abedin," says Baseer, who was then a student of elementary 1st year. The show was a combined effort by the teachers and students of the GIA. For today's students of art academies there is no such luck of putting up a show through such collective effort where all the stalwarts of the country are active participants.

"The visitors used to swarm the exhibition. We, the students of the GIA, used to put up posters in different schools of Dhaka, and the teachers of those schools used to bring the students in groups in horse-drawn carts to the exhibition. We worked as volunteers to explain what water colour, lithograph or even oil colour meant," recalls Baseer. At that period, when artistic activities were confined to a handful of students and teachers of the newly established GIA, the only art academy in the country till 1970, special care was needed to educate the public regarding art. GIA was established by Zainul Abedin with the help of Kamrul Hasan, Anwarul Haq and Safiuddin Ahmed in 1948. Its inception marked the beginning of the art movement that followed.

Today, the art students of the IFA can hardly imagine the need for putting up posters in the schools around

Advance-2, Shahabuddin Ahmed

Dhaka. At present, there is little activism on their part to promote art. They live in a changed situation, where the need for banding together to promote art has subsided. Today's artists are not burdened with such duties; they can afford to invest all their energy to make art and to put up exhibitions. The movement or the organised efforts in the fifties and the sixties have certainly contributed to the situation that now exists.

"The modern art movement gained ground in the then East Pakistan, the west wing was less responsive to the influence of the West. They did not start to practice abstract art, we did," says Baseer. Though the movement of the sixties was heavily influenced by few prominent American Abstract Expressionists like Mark Rothko or Cliford Still, it paved the way towards liberalisation. It is to this liberalisation that Bangladesh's art owes much of its present accomplishments.

Monirul Islam, an artist who has been living in Spain since 1969 and who has become a

|

Composition by Nasima Haque Mitu, one who relentlessly trys to relate abstract principles with recognisable objects |

national figure in that country, believes that "art transcends the national boundary, as colour, line and form has no national identity". This very ethos has more or less governed the art world of Bangladesh since the beginning. However, there is this idea of regional identity or the question of producing art that carries the imprint of the socio-political reality of the country that has come to the surface from time to time. In the post-independence era, painter Shahabuddin, who has been residing in France for the last 21 years and the sculptor Rasha have provided the antidote of the purely aesthetic world of colour, line and form. These two artists, in their passion for depicting the legacy of the War of Independence, brought a nationalistic fervour to their art. From the same end of the spectrum came a few social critics, who strove to formulate political commentaries through their works while doting on German Dadaists' take on social reality. Nisar Hossain, Shishir Bhattacharjee, Dilara Begum Joly, Nazlee Laila Mansur and Dhali Al Mamun are the ones who have consistently been producing works in the form of social critic. Apart from these few exceptions, Bangladesh's art scene is replete with works that either stems from the natural splendour or from the abstract ethos of harmonious agglomeration of line, form and colour fields.

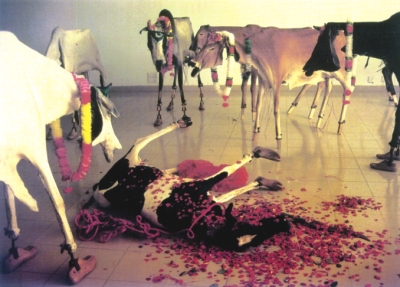

Though, art primarily is the embodiment of concepts, it is also a saleable commodity. But, there are artists who are stubbornly practicing a language of art, namely installation art, which is non-saleable. And they take pride in it too. Artists like Mahbubur Rahman and Tayeba Begum Lipi have shown a resolve to continue their works in the genre of installation art. Beginning in the 1990s the duo has come a long way. They have

|

Pretend by Mahbubur Rahman tackled the issue of animal slaughter using the language that has recently become all the rage, installation |

established Britto, an artists' organisation that promotes installation art. Although, the present art scene is marked by individual artists trying to make headway on their own, Britto has revived the old way of taking strides to reach a collective goal. However, not everyone sees progress in the strides that Britto has been taking. Baseer has his reservations about installation art. "It is not an art form that has developed from within the culture, it seems like an imposed idiom; we don't have the social condition yet for such expression of art," he expresses his disapproval. He has similar criticism of the practitioners of pure abstraction. "It did not grow out of our own socio-economic realities," he says. Yet he is enthusiastic about the present art scene. "I am astonished to see how the art scene has evolved. In the absence of travelling shows of original arts from Europe and America, in a country that still doesn't produce any of the art materials, the dedication of the young artist is certainly something to reckon with," he exclaims.

Exposure to world art certainly has its repercussions. "It is the Asian Art Biennial (AAB) that has a revolutionary effect in art practice of Bangladesh," opines Baseer. Though AAB brought arts mainly from the Asian countries, it has changed the outlook of the students of art for good. "It is through this show that artists of Bangladesh first witnessed large-

|

| Rasha's For Independence, a style fuelled by nationalism |

scale installation by Japanese artists," says Subir Chowdhury, the former Director of the Fine Art Department of the Shilpakala Academy, the organisation that plans and organises AAB shows. Whatever diversification took place in the last two and a half decades, the AAB has worked as the catalyst in the process. Chowdhury, who is now the director of the Bengal Gallery of Fine Arts, believes that the inception of the Shilpakala Academy had an impact on the art scene as a whole. "Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy (BSA) began its journey from October 1974 and the first of the annual shows began on March 15, 1975," recalls Chowdhury. At first the show used to be organised once every three years. It is from the eighties that the show became a biennial event. There is another show of BSA that used to ignite the enthusiasm of a lot of young talents: the Young Artists' Exhibition, which was also a biennial event. "Long before the AAB, these are the shows that revitalised the artists working to make a headway in the art scene of the country. The artists who were awarded in these exhibitions became well-known at the national-level," Chowdhury reiterates.

The 1980s and the 1990s were governed by the BSA-- organised national-level

|

Figure and Environment-1, by Sheikh Afzal, the artist who bases his art on academic realism |

|

One of the early works by Mohammad Iqbal titled Conversation-2, Iqbal is currently living in Japan |

exhibitions. However, in the new millennium these shows do not exert the same level of influence on the art scene of the country. Today, the activities on the part of the private galleries and the artists themselves have outweighed the importance of the national-level exhibitions. The Bengal Gallery of Fine arts, La Galerie of the Alliance Francaise, as well as the Zainul Gallery of the IFA have become the most frequently used venues of Dhaka. While the Bengal Gallery shows are fully sponsored by the Bengal Foundation, and the La Gallery shows are partly sponsored by the Alliance Francaise, all shows at the Zainul gallery are organised by the artists themselves. If the number of exhibitions as well as the sale of art is considered to be the guide, the art scene of Dhaka has reached a phase when at least few renowned artists enjoy a steady sale. For the young and the striving, the market still remains an unresolved puzzle. Sales from the artists' organised exhibitions are still sporadic. However, for the handful of private galleries, prospects are gradually looking brighter.

Goutam Chokraborty, owner of the newly established gallery, Kaya, which was launched on May 2004, feels that the market is growing. "There has been a change in the art market; the new generation of buyers are buying art works out of interest. Realising the fact that the price of the works one day would shoot up, they are buying the works of young artists," says Chokraborty. What he sees as the impediment to the smooth operation of any gallery is the non-professional approach of the artists. "Artists of Bangladesh still fail to meet deadlines, some of them often miss the schedule of their own show, this isn't congenial to the gallery business," Chokrobarty points out.

Whether an artist is able to sell his or her work or not, the merit of the work is an altogether different matter. It is independent of the need of the market, believes Wakilur Rahman, an expatriate artist living in Berlin since 1988. "There are works that are being sold because there are spaces in people's homes that need to be filled. Apartments have come up, and the owners need to buy art works that would suit their environment. I would not call them genuine buyers. Art is being considered like any other product that they buy," Rahman is emphatic. He sees a lot of artistic productions that cater to such needs, and says that in such works there is no possibility of "experimentation," "search for new theme or new language".

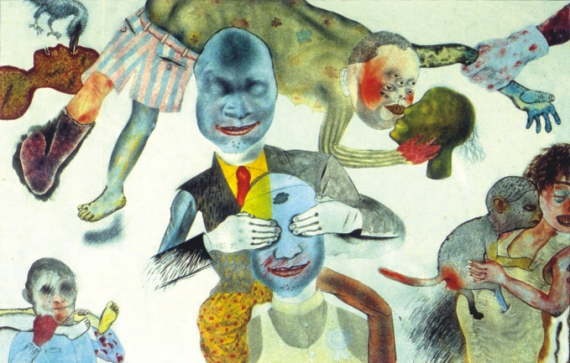

The usual mixture of social criticism and political commentary, Come and See the Game by Shishir Bhattacharjee

"Bangladeshi artists are emotional and intuitive; as such they have failed to remain at the apex of all the development or the leap that marks the new era, with the influx of the internet, the mobile, (though all these were made possible courtesy of the West). The artists have not shown the innovation in his theme, or surface or in the method of his communication," Rahman lements. He shares a kinship with the artist Nisar Hossain, who like Rahman began his artistic journey in the early 1980s. "There is no doubt that the question of development in art in itself has become shrouded in doubt. Art has been diversified in the last two decades, but it has not progressed," he argues. Hossain is of the opinion that Bangladesh could not produce a single influential artist in the last twenty years. "What Kamrul Hassan had done by marrying the patuas' style with that of the cubist manner, or SM Sultan had done by aligning his concept with the pictorial language, there has been no match of that in the recent past," he continues. He cites a saying of Zainul Abedin in this context. "Zainul once said during the Pakistan era, 'In 1943 I painted to raise a voice against the famine, and since 1947, I have been painting against the famine of taste that persists among the people,'" Hossain quotes the master stressing the fact that in a Muslim dominated populace, where a section of people is becoming educated and rich and are in need of aesthetic stimulation, the very act of producing art is a step to raise the collective taste for things that are artistic. "The present art scene mostly comprises of works that go to enhance the taste of the people, rather than being original pieces that may challenge the viewers," says Hossain. He also argues that the art scene of Bangladesh has so far been successful in "introducing the already overused Western idioms in the Bangladeshi soil".

After Having A great Deal of Imparialism We are Waiting for Mr Becket, by Ronni ahmed, an artist who melds absurdity with imagination

Bangladesh has secured a lot of brownie points in the form of individual talent. But as whole it lacks the most important element of all, the critical analysis that constantly provide feedback to the artists. "We lack a 'total art culture'. The aspect of criticism as well as theoretical practices that feed the imagination of the artist are absent in Bangladesh. On top of that, art is now perceived as an insular activity, it was not so during the time of Zainul or Kamrul. The interaction among people who are engaged in producing literature, drama, or other kinds of art is an important factor that is now missing," says Hossain. He emphasises that if an artist wants to be contemporary he or she needs to interact with the people from other fields, the total art culture is a result of interrelated and collective actions. This is where the present art scene has shown its weakness, all creative actions on the part of the artist seem divorced from the overall cultural milieu of the country. Artist Ronni Ahmed feels the need of introducing art education at school-level; "this may bring about a constructive change," he believes.

|

Image by Mohammad Fockhrul Islam, one of the avid abstractionists from the new generation artists |

However, as making art is a solitary practice, so is the fight to survive in an art scene that is not so accommodating to newer concepts. "It is an individual fight. The artist who wants to add to the already existing repertoire must deny the academic power structure as well as the trends of the past," says Ahmed. "There are two kinds of arts practiced in Bangladesh one that pleases the establishment and the other that proposes an alternative, both are stilted on borrowed ideas, what we really need is an Avant-garde element that would deny the trends and set out to explore newer grounds," believes Ahmed.

As a young artist he knows that it is a constant struggle for any artists who set out to create something new and original. In Dhaka there is a ready market for the kinds of art that compromises this very idea. "For any genuine artist the aspiration for a novel idea

|

| Alluvial Faces by Kalidas Karmakar, one of the older generation artists who often resorts to installation to express himself |

always takes precedence to the thought of the sale of the artistic creation that stemmed from that very idea," adds Ahmed. If these are the preconditions of making art, then Bangladesh's art scene has not much to crow about. All disappointments aside though it is in the field of art that the glimmer of hope is still flickering. The most significant feature of the post-indenpendence art scene is the emergence of women artists. Artists like Rokeya Sultana, Nazlee Laila Mansur and Ferdusy Priobhashini, who is a self-taught artist, by securing their place in the broader horizon

|

Relation by Rokeya Sultana. She has been steadfast in her endeavour to create child-like imagery |

have paved the way for a lot of new generation women artists. Names like Shahabuddin Ahmed and Monirul Islam, the expatriate artists who have made some headway in the international arena, still fuel the steam of national pride. These artists along with the pioneers who gave the country an identity have been a source of inspiration for many a denizen of the art world. As Hossain feels that it is up to the new generation artists to reconcile the tradition of the land with that of the advanced European modes, and make something new out of it, it is also true that it surely is not possible without the full understanding of both the worlds. The advancement that many feel have so far eluded the artists of today's generation is only possible knowing where we stand and what we should borrow. Bangladesh has the ingredients; all it needs is an original formula to hurtle ahead. HIGH PRICES

Way back in 1966, from a show by Kamrul Hasan at Art Ensemble, the first gallery in Dhaka, not a single art piece was sold, though most of the pictures were priced in between Tk 50 to Tk 100. After the death of the maestro in 1986, the price of his works shot up. At present even a simple ink sketch of Hasan may fetch more than a lakh depending on its condition. In the first two decades after the independence, prices of art went up at a slow pace. In the third decade the price of art simply skyrocketed. It was SM Sultan and Shahabuddin Ahmed, whose works first fetched lakhs of taka. As a living artist Shahabuddin was the first man to have works, the price of which exceeded the six-figure slot. It was in his solo exhibitions organised by Shilpangan, a private gallery, during the early and mid 1990s that he commanded such exorbitant prices. Fortunately for many middle-class collectors, his art was within the reach even in the 1980s; his large canvases were then priced in between 10,000 to 15,000. At present many art lovers with limited means find works of artists of renown to be prohibitively priced. In the last fifteen years, art of the recognised masters has become the commodity only to be craved and enjoyed by the rich.

Copyright

(R) thedailystar.net 2005 |

| |